· retrotech · 6 min read

The Rise and Fall of Lycos: Lessons from the Early Internet Era

Lycos went from Carnegie Mellon research project to dot‑com poster child and then to a cautionary relic. This article traces the arc of Lycos’s rise and fall and draws hard lessons every digital startup should heed.

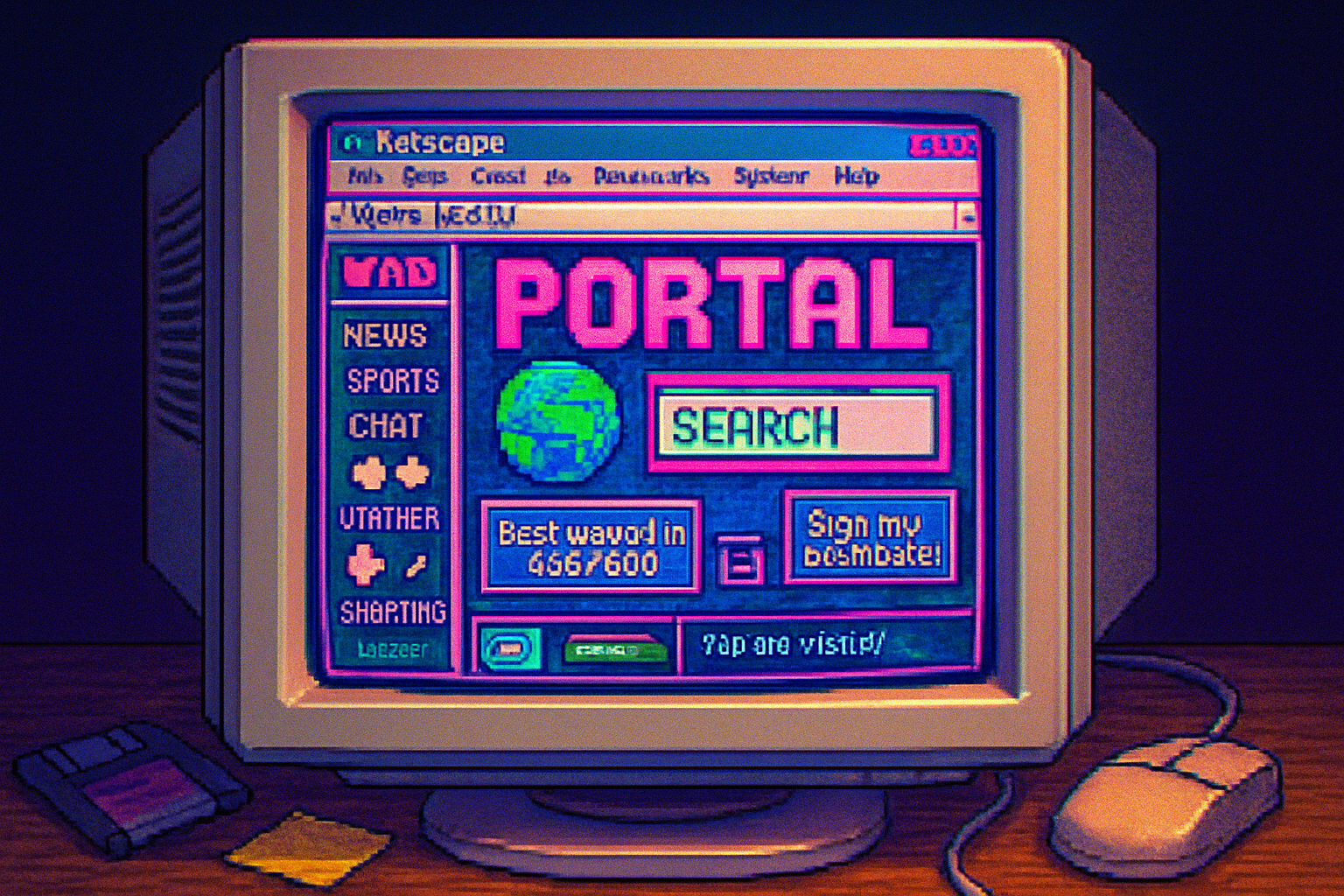

Imagine it’s 1996. You get a dial‑up tone, there’s a hiss from your modem, and a chunky homepage loads with the ecstatic slowness of a sunrise in a pixel world. Lycos sits at the center of your internet universe: search, email, free web hosting, a portal full of content. The name - borrowed from a wolf spider - feels clever and a little ominous. The future looks boundless.

What a difference a few years makes. Lycos, once a pioneering search engine born at Carnegie Mellon, became a poster child for the dot‑com boom and bust. At peak valuations it was treated like a golden calf; within a few years its market worth had been whittled to dust. There’s no single villain here - only a chain of decisions that, together, read like a manual of how to squander an early lead.

A quick timeline (so we don’t argue about dates)

- 1994 - Lycos is born as a search engine project at Carnegie Mellon University [source: the Lycos Wikipedia page].

- Late 1990s - Lycos commercializes and expands into a portal model, acquiring content and community properties.

- 2000 - Lycos is caught up in the dot‑com fever - sky‑high valuations and an acquisitive streak.

- Early 2000s - The dot‑com crash and strategic drift sink Lycos’s value.

For a concise reference you can start with the public timeline on Lycos’s Wikipedia page: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lycos and compare snapshots of its homepage archived in the late 1990s: https://web.archive.org (search Lycos snapshots).

Why Lycos mattered

At the time of its founding, search wasn’t an obvious business the way it is today. Early users navigated directories, portals and bookmarks. Lycos proved that a crawler + indexing + ranking system could turn the mess of the web into something you could query. It was one of the first projects to show that relevance algorithms - not editorial directories - could scale.

That technical insight made Lycos important. But being first is a gift and a trap.

The strategic mistakes (read: how hubris eats product)

Lycos did many things well early on. It also made several recurring errors that are now textbook warnings for startups:

- Losing focus by turning into a portal

- The magic of Lycos was search - fast, useful, algorithmic discovery. Instead of doubling down, management pushed Lycos to become a portal and media company - content, free web hosting services, email, and dozens of acquisitions.

- The portal model can work (see - Yahoo), but it competes on attention, editorial curation and user experience - skills different from building world‑class search. The result? The product DNA that made Lycos special was diluted.

- Acquisitions without integration

- Lycos bought a slew of properties (free web hosts, communities, niche services). Acquisitions can buy growth. They can also buy chaos - incompatible cultures, duplicated tech stacks, and backward integration burdens.

- Purchased attention wasn’t converted into loyal core users. The company ended up maintaining an increasingly heterogeneous portfolio that bled cash and focus.

- Monetization by clutter

- Early monetization favored display ads, flashy banners and portal page real estate. That worked during the boom - for a while.

- But prioritizing immediate ad revenue led to clumsy UX - pages that screamed for clicks instead of delivering utility. When a cleaner, faster competitor came along, users noticed.

- Underestimating the importance of product experience and algorithmic improvement

- Search is an arms race of relevance. Google’s minimalist interface and relentless engineering refinements increasingly outclassed older players.

- Lycos treated search partly as legacy plumbing while betting on new verticals. The investment tradeoffs were fatal - incremental UX and algorithm upgrades couldn’t match competitors who doubled down.

- Timing and market forces

- The dot‑com bubble created insane valuations and bad incentives. Growth-at-all-costs, easy capital, and public markets rewarding eye‑popping top lines made strategic discipline optional.

- When the macro environment corrected, poor unit economics and flimsy integrations were exposed like cheap drywall in a storm.

Concrete moments that mattered

- The expansion into portal services and the spree of acquisitions created short‑term growth but long‑term debt - a Frankenstein product with no coherent spine.

- The sale and re‑sales during and after the dot‑com era compressed Lycos’s valuation dramatically. What had been celebrated as a trophy asset was sold for a tiny fraction of its peak value in the years that followed.

(For a tightly packed timeline and list of acquisitions, see the Lycos article on Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lycos.)

Lessons for founders (each lesson illustrated with a Lycos example)

Focus trumps “portfolio” in early product market fit

- Don’t confuse possible adjacencies with the business you must perfect. Lycos had a search product to perfect; instead it built a patchwork portal.

Acquire only when you can integrate

- Buying users is easy; turning them into loyal customers is hard. Acquisitions should have clear integration pathways - technical, cultural and product - or else they store liabilities, not assets.

Protect the core experience

- If search is your core, make search better every quarter, not every other fiscal year. Customers remember speed and reliability; they remember mercy for their attention.

Monetize without destroying your brand

- Ads pay the bills. Bad ads and obtrusive UX destroy long‑term value. The short gain of banner money is often dwarfed by the long loss of trust.

Beware of market narrative as strategy

- ‘We’ll be the portal, the media company, the community, the everything’ is a seductive chorus during frothy markets. Strategy tied to narrative, not unit economics and product metrics, tends to fail.

Respect the winners’ advantages

- When competitors (like Google) invest relentlessly in a technical moat - algorithms, data centers, user experience - you either match that commitment or find a defensible niche.

A few counterintuitive notes (because history is messy)

Diversification is not always bad. If a company has the managerial capacity and integration systems, buying complementary products can create durable networks. The error isn’t diversification itself; it’s diversification without capability.

Timing matters as much as talent. Had Lycos been more disciplined, it might have survived as a profitable niche player. But timing - both of capital flows and user behavior - amplified mistakes.

The human angle

It’s easy to turn Lycos into a parable about greed and mismanagement. That’s comforting but lazy. The real story is human: engineers who loved building search, managers who wanted impact, investors seduced by headlines, users who loved the convenience of portal pages. When incentives diverge - engineers optimizing for relevance, managers for revenue and investors for exit velocity - products die a slow death of fragmentation.

Lycos’s decline was not an act of villainy. It was a series of small, plausible decisions, each reasonable in isolation and lethal in aggregation. That is the cruelest lesson: markets rarely punish one stupid move. They punish the accumulation of small compromises.

Final, blunt takeaway

If you’re building something early and beautiful, defend its center. The internet is littered with companies that traded a remarkable product for a diluted, uncompetitive portfolio and then wondered why users left. Lycos teaches that strategic clarity, product obsession, ruthless integration discipline, and respect for the user’s attention are not quaint ideals - they are survival mechanisms.

Lycos didn’t fail because it was first. It failed because it forgot what it was first at.

References

- Lycos - Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lycos

- Web archives of Lycos homepages from the late 1990s: https://web.archive.org