· retrotech · 6 min read

Infoseek vs. Google: A Clash of Search Titans

A comparative look at how two search outfits-Infoseek, the hopeful 1990s portal, and Google, the academic upstart-chose radically different paths. One chased advertising and portals; the other optimized relevance, scale, and a new ad model. The result: very different destinies and lessons for building enduring technology.

A young internet user in 1998 might have used Infoseek on the way to Yahoo!, then clicked an animated banner promising free screensavers and a ‘Go’ portal. Two years later that same user typed a query into a stark white box and got an answer so good they stopped caring about screensavers.

This is a tale of two instincts: one company built a façade to monetize attention, the other built a better way to find things. The first flamed out; the second rewired the world.

Origins: a portal and a paper

Infoseek arrived early. Launched in 1994 by Steve Kirsch, it was one of a cluster of mid-90s search services-AltaVista, Yahoo!, Lycos-trying to make sense of the rapidly growing web by blending search with editorial curation and advertising [Infoseek].

Google’s story began in a Stanford dorm room in 1996. Larry Page and Sergey Brin weren’t trying to build a portal or sell banner impressions; they were solving a ranking problem. Their innovation-PageRank-measured a page’s importance using links like academic citations, producing dramatically better relevance than existing keyword-frequency methods [PageRank paper].

- Infoseek - portal-first, commercial instincts, early mover.

- Google - research-first, algorithmic breakthrough, academic pedigree.

Technical approaches: prominence vs. relevance

Infoseek’s ranking relied more on text matching, on-site signals, and commercial arrangements-typical for search services at the time. Many early engines treated the web as a collection of keyword-stuffed documents and adjusted results to surface advertiser-friendly or editorially curated pages.

Google rewired that frame. PageRank turned the graph of the web into a signal. Links became votes, and the algorithm married that structural signal with content-based features. The result: fewer noisy hits, more directly useful results.

The difference is like two librarians. Infoseek’s librarian reads the index cards and also answers because his friend pays him to. Google’s librarian ignores club membership and follows citations to the book everyone else keeps mentioning.

Reference: Brin & Page’s original paper explains the design in crisp form [The Anatomy of a Large-Scale Hypertextual Web Search Engine].

Business models: portals, banners, and the birth of intent advertising

Infoseek’s revenue instinct was obvious in the 90s: build a portal, aggregate eyeballs, sell display ads and promotions. The portal model traded on attention and a curated front page. That approach thrived in an era when broadband was immature and user attention was consolidated.

Google took a different tack. It held out on heavy-handed display monetization and instead focused on getting queries right. Only after winning users did Google create AdWords and later refine paid search into auction-based, intent-driven ads. Ads were contextual, tied to user queries, and measurable. That alignment of ad format and user intent proved far more valuable than splashy banners [AdWords].

Short version:

- Infoseek - attention-first, portal play, display-driven.

- Google - query-first, product-led, monetization second-and better matched to intent.

Experience & product philosophy: clutter vs. clarity

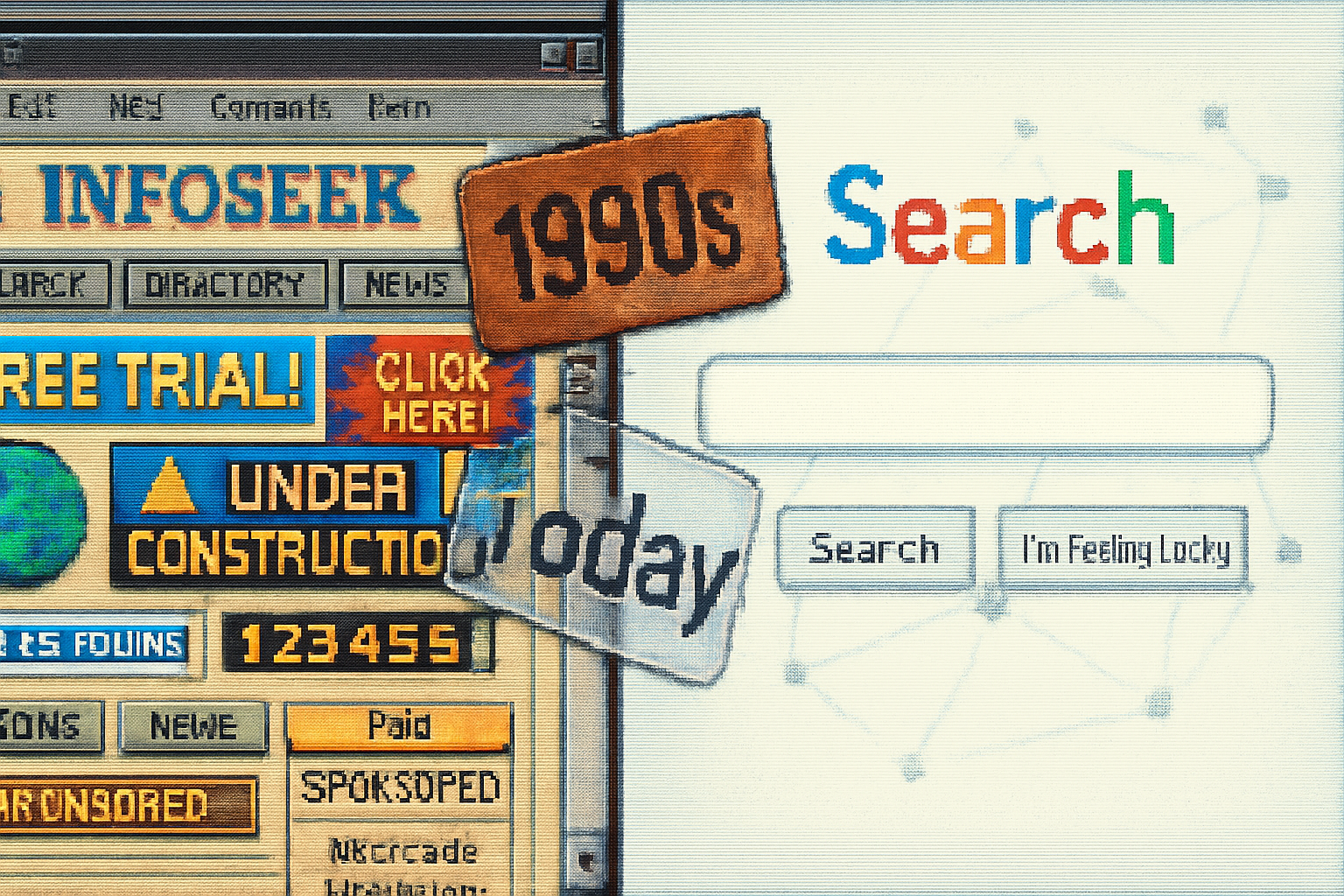

Compare screenshots from 1997 and 2002 and the message is stark. Infoseek’s pages read like a trade show: boxes, links, promotions, and the faint smell of sponsored placement. Google’s homepage? A single input and the quiet confidence of a tool that trusts the product.

Simplicity wasn’t aesthetic masochism. It was product discipline. A cleaner interface reduced friction and let Google iterate fast on relevance metrics, A/B tests, and new features like snippets and caches. Meanwhile, portals were busy optimizing around eyeballs.

Corporate strategy, partnerships, and timing

Infoseek’s fate was also shaped by bigger corporate moves. In 1998 Infoseek became part of Disney’s GO Network, a move that folded a search engine into a content-and-portal conglomerate [Go.com]. Portals wanted scale and content; entertainment companies wanted distribution. The web was still socially and commercially immature, and corporate consolidation seemed logical.

Google resisted those temptations. It stayed focused, independent, and tightly controlled its product roadmap. That allowed it to scale infrastructure, attract engineering talent, and keep product and monetization tightly coupled.

Timing mattered too. Google arrived when the web’s link graph had enough structure to make PageRank truly effective. By then users were starting to expect search to be useful, not just a portal gateway.

Culture and engineering: disciplined craftsmanship vs. commercial urgency

Infoseek’s team needed to be marketers, deal-makers, and engineers. That’s a hard trio to harmonize. Portals often rewarded growth metrics and partnerships more than deep engineering craft.

Google’s culture-rooted in research, hiring elite engineers, and obsessing over metrics-pushed relentless improvement in crawling, indexing, ranking, and infrastructure. The company invested heavily in distributed systems and efficiency, which paid off as query volumes exploded.

Why Infoseek faltered

Several factors combined:

- Misaligned incentives - Portal economics rewarded attention aggregation and short-term ad deals rather than long-term investment in ranking quality.

- Corporate dilution - Being absorbed into a media portal (GO Network) shifted priorities toward content and cross-promotion [Go.com].

- Product clutter - A user experience optimized for ad units and partner links eroded the core value of good results.

- Competitive crowding - The late 90s saw fragmentation-AltaVista, Lycos, Yahoo!-and a winner-takes-most dynamic that favored a superior search experience.

Put simply: Infoseek played to the 1996 playbook while the web evolved into a place that rewarded precision and scale.

Why Google won-beyond luck

Google’s success wasn’t accidental or merely timely. It followed from a set of durable choices:

- Algorithmic superiority - PageRank transformed relevance and made Google measurably better for many queries [PageRank paper].

- Product-first focus - Simplicity and obsessiveness about quality kept users loyal.

- Monetization fit - AdWords tied ads to user intent, producing higher value per query than banner-centric models [AdWords].

- Engineering scale - Investments in distributed systems let Google handle growth without collapsing under its own success.

- Cultural coherence - Hiring from research circles, emphasizing metrics, and preserving a founder-driven road map.

These elements amplified each other: relevance created users, users created queries, queries were monetizable in a way banners never matched.

Legacy and the lessons for builders

Infoseek’s disappearance isn’t an indictment of 90s entrepreneurs; it’s a case study in strategic mismatch. The company did what 1995 logic rewarded: make a portal, sell attention. The web’s economic and technical vectors shifted under its feet.

Takeaways:

- Product-market fit changes. What sells today can be obsolete tomorrow.

- Monetization must align with value. Ads tied to intent (search) beat ads tied to attention (banners) in the long run.

- Technical differentiation can be defensible and durable-if it’s paired with disciplined execution and culture.

- Corporate mergers that dilute product focus often kill emergent tech advantages.

For historians of tech, Infoseek is a cautionary footnote; for product people, it’s a lesson in choosing which instincts to follow.

Closing: a last, sharp point

Infoseek tried to be where the eyeballs were. Google asked: what happens if the answer appears so fast and so right you stop thinking about portals at all? The latter question is what shaped the modern web. One company chased attention. The other engineered relevance. One faded into a portal graveyard; the other built the map.

References

- Infoseek - Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Infoseek

- Google - Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Google

- The Anatomy of a Large-Scale Hypertextual Web Search Engine (Brin & Page, 1998): https://infolab.stanford.edu/~backrub/google.pdf

- Go.com / GO Network - Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Go.com

- Google AdWords - Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Google_AdWords