· culture · 7 min read

The Last Tape: A Journey Through the VCR Apocalypse

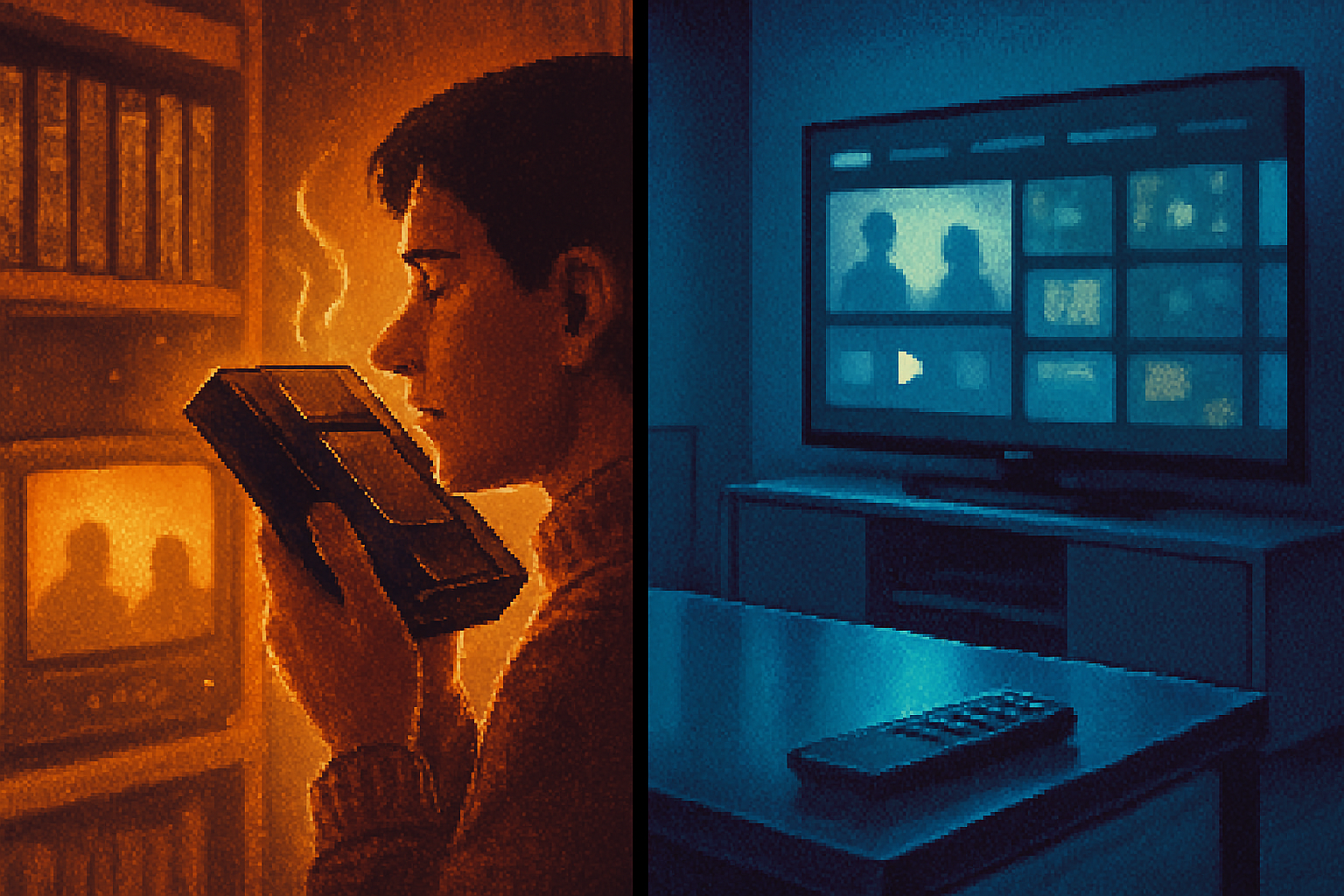

A nostalgic, investigative look at how the VCR shaped 90s culture - from rental-store rituals to time-shifting - and why the age of magnetic tape ended so quickly. An argument about what we lost when physical media surrendered to streaming, and why that matters now.

It begins with a pencil.

Not metaphorically. If you grew up in the 90s, you know the sight: a dusty living-room table, a chewed Bic and a cassette whose innards had sighed to a halt. Precision, patience, a twist of plastic - and the tape wound back into submission. That tiny act - elementary, domestic, mildly heroic - tells the whole story of the VCR era: it was tactile, improvised, and intimately ours.

The VCR was more than a machine. It was a cultural anchor. It rewired time and interior life: you could record last night’s news, fast-forward through commercials, or rent a movie and make an evening of it without asking for permission. Then, almost overnight, those rituals were declared obsolete. This is the story of how a device that dominated living rooms vanished - and what its death says about media, memory, and taste.

How a clunky box became the family hearth

The videocassette recorder (VCR) arrived out of an odd industrial race: Sony’s compact designs and JVC’s VHS format duked it out in the 1970s and early 80s. VHS ultimately won the format war for reasons that were as much social as technical - longer recording time, looser licensing, and slightly better industry alliances - turning the VCR from a niche professional tool into a ubiquitous household appliance [https://www.britannica.com/technology/videocassette-recorder; https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/how-vhs-beat-betamax-180967811/].

By the 90s the VCR had matured into something like American civic furniture. Owning a VCR meant:

- Time-shifting television (the ritual of recording a show and watching it later).

- The rental economy (one city block could host three video stores with different curations).

- The rise of new viewing habits - repeated viewings, homemade compilations, and the art of pausing at the precise moment a movie says something that mattered.

Video rental stores deserve a paragraph of their own. They were retail meets recommendation engine: clerks with guilty pleasures, hand-lettered signs, late-fee tedium, and the faded “Be Kind, Rewind” morality operating like a civic ethic. Blockbuster’s rise transformed these rituals into a national chain and a kind of cultural grammar around what to watch and when [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blockbuster_LLC].

Rituals the VCR made possible

The VCR made private time public in a new way. A few of its civilizing habits:

- Time-shifting - You could watch your broadcast content on your schedule.

- Home archiving - Birthdays, local parades, amateur documentaries; many family histories exist because of VHS.

- Discovery through serendipity - Shelf-browsing generated recommendations that algorithms now covet.

- The communal event of renting - movies were part of negotiation and identity - what you chose to bring home said things about you.

These rituals felt trivial until they were gone.

The slow-motion footnotes that became an avalanche

Say “VCR decline,” and most people imagine a sudden replacement by Netflix and streaming. That’s a convenient myth. The real death was a concatenation of technical, economic, and industrial decisions, each one eroding the VCR’s throne:

- The DVD’s arrival - Compact discs of moving images arrived with sharper picture, no rewinding, better menus, extra features, and smaller packaging. Consumers recognized the qualitative leap almost immediately. Studios pivoted; shelf space narrowed for tape [

- Economics and manufacturing - DVDs were cheaper to produce at scale, cheaper to ship, and easier to stock in stores. For studios, margins improved.

- Piracy and digital replication - Digital formats made copying simpler and cleaner; the industry responded by embracing formats that supported new business models (and new protections).

- Distribution shifts - Retailers and rental chains rapidly adopted DVD because customers asked for it. The inertia of the industry was toward anything that reduced friction.

- The rise of Internet distribution and services - Netflix (founded in 1997) started as a DVD-by-mail service and would later exploit broadband to deliver streaming. Streaming didn’t topple VHS; it simply completed a transition that DVDs had already started [

Put simply: the VCR was outcompeted on convenience, fidelity, and economics. The tape’s physical inconveniences - fragility, tangles, rewind time, lower resolution - became anachronisms.

The last tape: cultural casualties and collateral gains

When a technology disappears, you get both losses and gains. The narrative that streaming is purely progress is too neat.

What we lost:

- Ritual and serendipity - Browsing a shelf is not the same as scrolling an infinite algorithmic grid. Physical curation had accidental discoveries.

- Material provenance and ownership - A VHS sits on your shelf and says, I was chosen. Streaming says, we can take it away.

- Local economies and social hubs - Independent video stores were neighborhoods’ cultural salons.

- Some archival durability - Magnetic tape decays, but digital files vanish too - when a studio pulls a title or an online service shutters, access disappears unless someone archived it.

What we gained:

- Instant access and convenience - No rewinding, no late fees, enormous catalogs at your fingertips.

- Better picture and sound - a genuinely better viewing experience for many.

- New business models that enabled more diverse production (and also, a new monoculture of winners).

The great paradox - better technology, poorer rituals

The VCR’s defeat reminds us of a recurring human pattern: we accept more efficient systems while forgetting the informal economies and rituals they replace. The VCR created private rituals (rewinding, labeling tapes) and public ones (rental nights). Streaming replaced those with algorithmic discoverability, curated playlists, and data-driven recommendation engines. The results are ambivalent.

Streaming is not neutral. It mediates taste with machine logic and corporate catalogs. When a film is removed from a platform or when licensing decisions favor the newest franchise, cultural memory narrows. Deletion in the digital age often feels less dramatic than a tape being snapped in half, but it can be more total: there is no second-hand shelf to rescue what’s been delisted.

Preservation, access, and the politics of media

There are fierce practical consequences. Archivists warn that magnetic tape decays and that digital formats require active preservation strategies. Both media demand care; neither is immortal. What adds urgency now is DRM and corporate control. Physical media can be hoarded by collectors; digital media can be made unavailable because of licensing or corporate failure. The lesson: forces of preservation are social, not purely technological. Libraries, museums, and communities matter [https://www.loc.gov/preservation/caring-for-collections/preservation-basics/audio-and-video/].

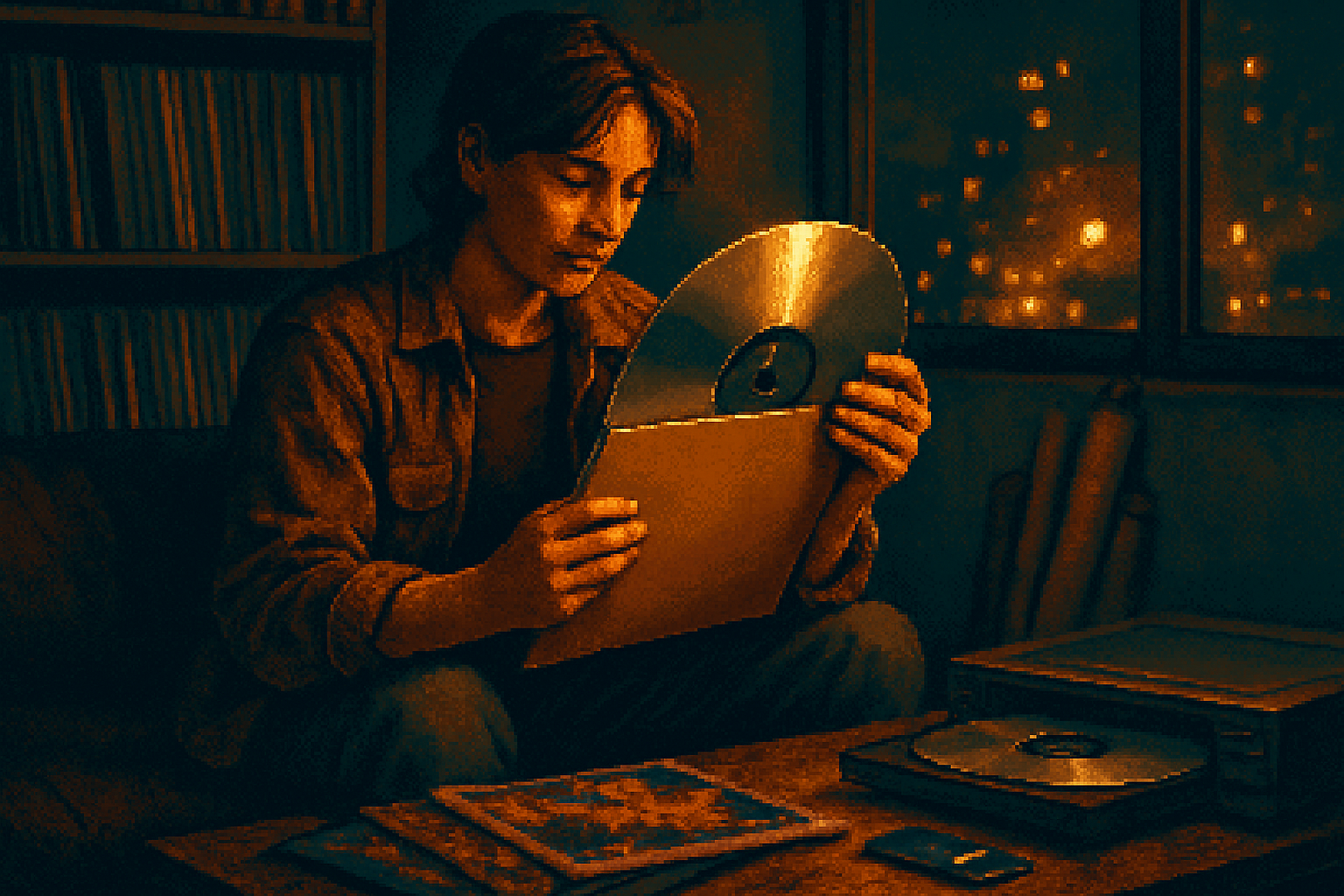

Nostalgia, fetish, and the boutique afterlife

If you think the VCR died without a funeral, look again. There’s a flourishing collector culture around VHS: boutique labels, art projects, and micro-pressings celebrating analog flaws. Nostalgia keeps alive an appreciation for the tactile and the imperfect. It’s not just sentiment; it’s a critique of a world in which choice is increasingly mediated by opaque algorithms.

Films like Be Kind Rewind caricatured the affection people had for rental stores, but there’s truth in the caricature: networks of social value and taste were embedded in those fluorescent aisles [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Be_Kind_Rewind].

What the VCR’s death teaches us now

- Technological convenience can hollow out civic rituals. Convenience is not value-neutral; it shapes how we relate to culture.

- Ownership matters. Physical objects anchor decisions and memories in ways licensed digital files do not.

- Preservation is proactive. If we want diversity and memory preserved across formats, public and nonprofit institutions must intervene.

- Cultural infrastructure requires care. Local media stores, archives, and community curators are part of the commons and need support.

A final spool of tape

We tell myths about technological inevitability because they comfort us. VHS did not “lose” because it was bad; it lost because a better and cheaper medium appeared, because business incentives realigned, and because consumers - rationally - adopted the superior product. But in that tidy story there’s a leftover ache: the tactile, domesticated rituals of the VCR are hard to monetize and easy to forget.

The last tape is not merely a relic. It’s a warning: the technologies we accept without question change not only what we watch, but how we remember and who we become. If you want to keep something from disappearing, you must either own it, archive it, or subsidize the social institutions that steward it.

And if you still have a VCR and a box of tapes in the attic, don’t throw them away. Tape is impermanent - but so is streaming. The difference is that a tape gives you something to hold while you decide what to do next.

References

- “Videocassette recorder,” Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/technology/videocassette-recorder

- “How VHS beat Betamax,” Smithsonian Magazine: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/how-vhs-beat-betamax-180967811/

- “DVD video,” Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/technology/DVD-video

- Blockbuster (company), Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blockbuster_LLC

- Netflix, Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Netflix

- “Be Kind Rewind,” Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Be_Kind_Rewind

- Library of Congress - Preservation basics for audio and video: