· retrotech · 6 min read

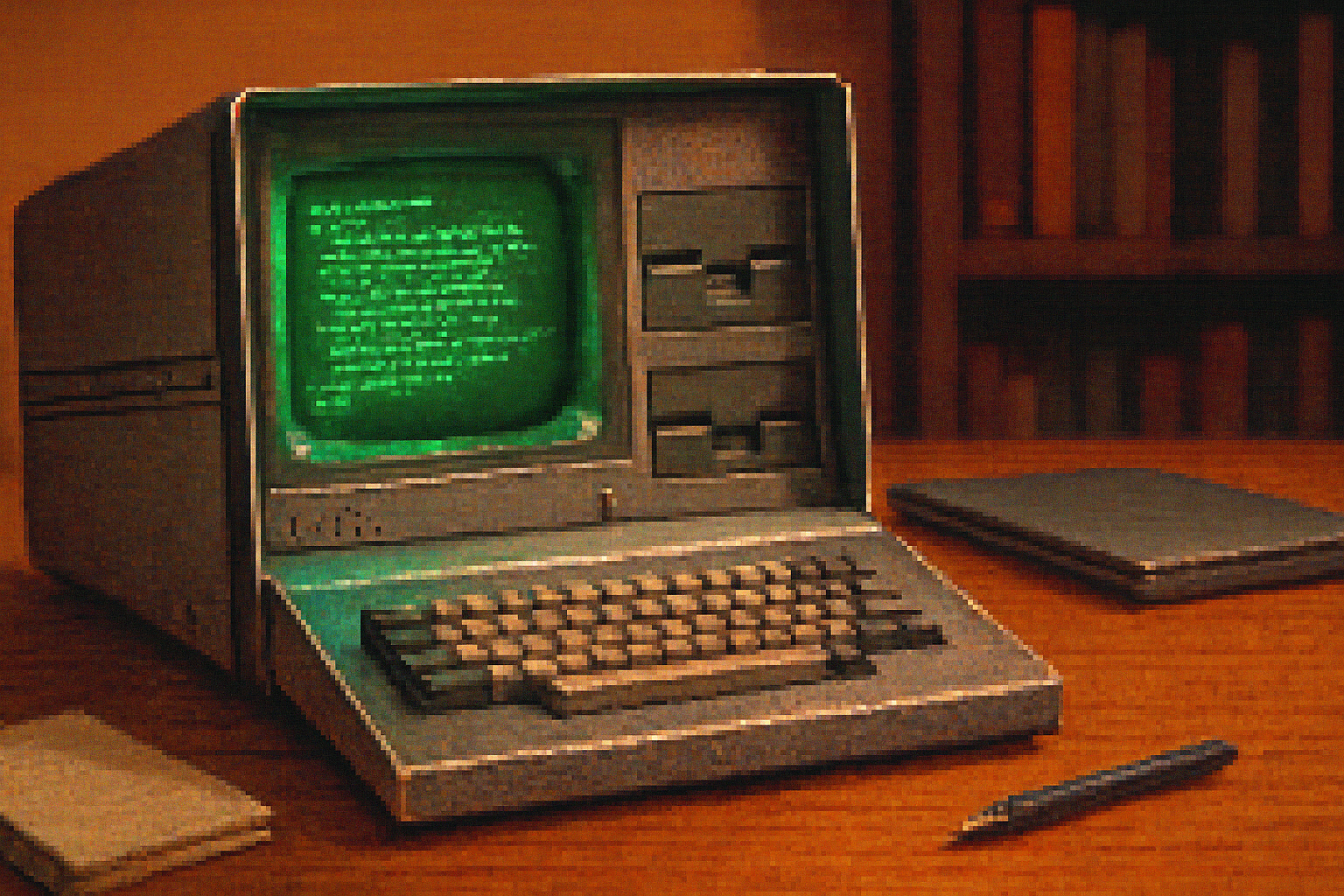

Retro Tech Resurgence: Why the Kaypro II is Making a Comeback

The Kaypro II - a slab of metal, a 9" CRT, and two 5.25" floppies - is enjoying a second life. This piece explores why collectors and hobbyists are drawn to this iconic 1980s 'luggable', what owning one actually means today, and how the machine embodies the broader retro computing revival.

I bought my first Kaypro II at a flea market for a pocketful of coins and a promise: “It turns on, sometimes.” It was heavy, smelled faintly of cigarette smoke and solder flux, and its metal shell suggested it might double as a blunt instrument. I took it home, fed it electricity, and watched a tiny green cursor blink on a 9‑inch CRT. The machine didn’t just boot - it arrived like an archeological artifact that still knew how to speak.

The Kaypro II: a quick field guide

The Kaypro II was introduced in 1982 by Kaypro Corporation as one of the early “luggable” personal computers, aimed at professionals who needed a portable-if cumbersome-office. Built around a Zilog Z80 CPU and running the CP/M operating system, it shipped with 64KB of RAM, dual 5.25” floppy drives, and a bright 9” monochrome CRT tucked into a rugged metal case.

- CPU - Zilog Z80 (typical clock ~2.5 MHz)

- OS - CP/M (the dominant business microcomputer OS before MS‑DOS)

- Storage - two 5.25” floppy drives (no internal hard disk)

- Display - 9” monochrome CRT integrated into the lid

- Notable - shipped with bundled software - apps like WordStar, accounting programs, and utilities were a major selling point

For background and technical detail see the Kaypro entry on Wikipedia and the machine profile on Old‑Computers.com.

Why is the Kaypro II resurging? The human reasons

Modern tech is invisible. Your cloud has no smell, your phone is a glass shard polished between fingers. The Kaypro is the opposite: tactile, mechanical, and very, very present. That radical presence is a huge part of the revival.

Tactile honesty

The Kaypro’s keyboard, its physical drive activity lights, the weight of its case - these are affordances modern devices have deliberately shed. People are drawn to technology that reveals its workings. It’s like preferring a mechanical watch to a smartwatch: you trade convenience for craft.

Constraint as a design virtue

Working within the limits of CP/M and dual floppies forces a discipline that feels refreshing. There is pleasure in producing something useful under constraints: smaller programs, careful file management, and actual planning. For many hobbyists, that discipline is creative oxygen.

Aesthetics and materiality

The Kaypro’s brushed metal shell, chunky keys, and utilitarian typeface have an almost Bauhaus sincerity. In an era of homogenous black rectangles, a Kaypro sits in a room and insists on being seen. It photographs well, too - hence the flood of Kaypro shots on Instagram, Flickr, and retro‑tech blogs.

Repairability and maker culture

Unlike sealed modern devices, Kaypros are accessible. You can open the case, read the circuit traces, replace capacitors, or adapt a modern disk controller. This compatibility with hands-on repair dovetails with the maker movement and the backlash against planned obsolescence.

Social signaling and community

Owning a kayak… sorry, Kaypro, signals membership in a particular subculture: people who read assembly listings for fun, who archive floppies, and who know the difference between BDOS and BIOS. Communities gather on mailing lists, forums, and Facebook groups, and at swap meets and vintage computer fairs like those organized by the Vintage Computer Federation.

Concrete examples: programs, projects, and shows

The Kaypro’s bundled software has been a huge part of its charm. Buyers in the early 1980s found themselves with a surprisingly complete office in a box - WordStar for word processing, SuperCalc‑like spreadsheets, and assorted utilities. Those packages explain why the Kaypro sold so well: you could do real work immediately.

Today hobbyists use Kaypros for:

- Restored, authentic offices - running the original apps on original disks

- Art projects - generating dot‑matrix output for printed artworks

- Teaching - demonstrating early OS design and limited memory programming

- Mods - retrofits that replace the internal electronics with Raspberry Pi systems while keeping the original keyboard and case

If you want to explore the software legacy, the CP/M software archives and the Internet Archive are goldmines.

Practical realities: collecting, restoring, and living with a Kaypro

Buying one is the easy part; keeping it alive is the project. Expect to encounter these common problems:

- Power supplies and electrolytic capacitors - old capacitors leak or lose capacitance, and power supplies can fail or bulge. Recapping and testing the PSU is a standard first step.

- Floppy drives and belts - belts dry out; read/write heads need cleaning and alignment. Surviving floppies can be brittle and grow mold.

- Corrosion and switches - aging connectors and switches may need cleaning or replacement.

- CRT issues - the integrated CRT is robust but not immortal; reflowed solder joints or bad high‑voltage circuits are occasionally implicated in flicker or no‑display conditions.

Restoration tools and techniques you’ll want:

Basic tools - multimeter, soldering iron, contact cleaner, nut drivers

Disk imaging - devices like KryoFlux (for floppy preservation) and software to dump and archive disks

Replacement parts - capacitors, drive belts, common logic chips; communities often trade parts

A practical tip: image original floppies to preserve the software immediately, then run programs in an emulator until the hardware is stable.

Emulation: authenticity vs convenience

If you want the Kaypro experience without hauling 20 pounds of metal up three flights of stairs, emulation is an option. CP/M emulators and Z80 simulators let you run Kaypro software on modern machines - useful for development, disk recovery, and nostalgia with a far smaller carbon footprint. But emulation lacks that particular tactile honesty: the sound of a drive head, the faint hum of a CRT, the subtle satisfaction of a physical media swap.

Where to find one and what to pay

Kaypros show up on eBay, local classifieds, garage sales, and at swap meets. Prices vary wildly:

- Non‑working units - often under $100

- Working but cosmetically poor - a few hundred dollars

- Clean, working machines with original documentation and software - higher, often several hundred dollars or more depending on the market and rarity of accessories

Beware shipping costs - these things are heavy - and the risk of buying “dead” hardware advertised as “untested.” When in doubt, learn the basic diagnostic questions and ask for photos of the power supply and front panel boot messages.

What the Kaypro revival tells us about technology culture

We tend to imagine nostalgia as mere sentimentality - a soft retreat into familiar shapes. The Kaypro resurgence is not only nostalgia; it’s a corrective. It announces, loudly, that technology need not be invisible, proprietary, or disposable. It reminds us that constraints breed creativity, that machines can be loved for their honesty, and that the history of computing is not a museum we visit politely but a toolbox we can reopen and use.

There’s also a political edge. Owning and repairing a Kaypro is an implicit critique of the modern upgrade cycle: instead of a sealed monolith that becomes waste in two years, you have a repairable object that rewards time and curiosity. In that sense, the Kaypro revival is ecological as well as aesthetic.

Final verdict

The Kaypro II’s comeback isn’t driven by a single factor but by the collision of many: tactile appeal, maker culture, aesthetic trends, and a sharp human appetite for authentic constraints. Some collect it as furniture; others as a working time machine. Either way, the Kaypro keeps behaving like what it always was - stubborn, useful, and entirely unwilling to be polite about its presence.

If you’re thinking about joining the revival, prepare for a hobby that is equal parts archaeology, engineering, and historical reenactment. The rewards are genuine: a machine that teaches you to think small, fix things, and appreciate the shabby poetry of old silicon and metal.