· culture · 7 min read

The Newton MessagePad: The Forgotten Progenitor of Modern Tablets

The Newton MessagePad was a strange, brilliant, and messy ancestor of today's tablets. This piece traces how its handwriting recognition, apps, and design experiments prefigured features we now take for granted - and why it was canceled before the world was ready.

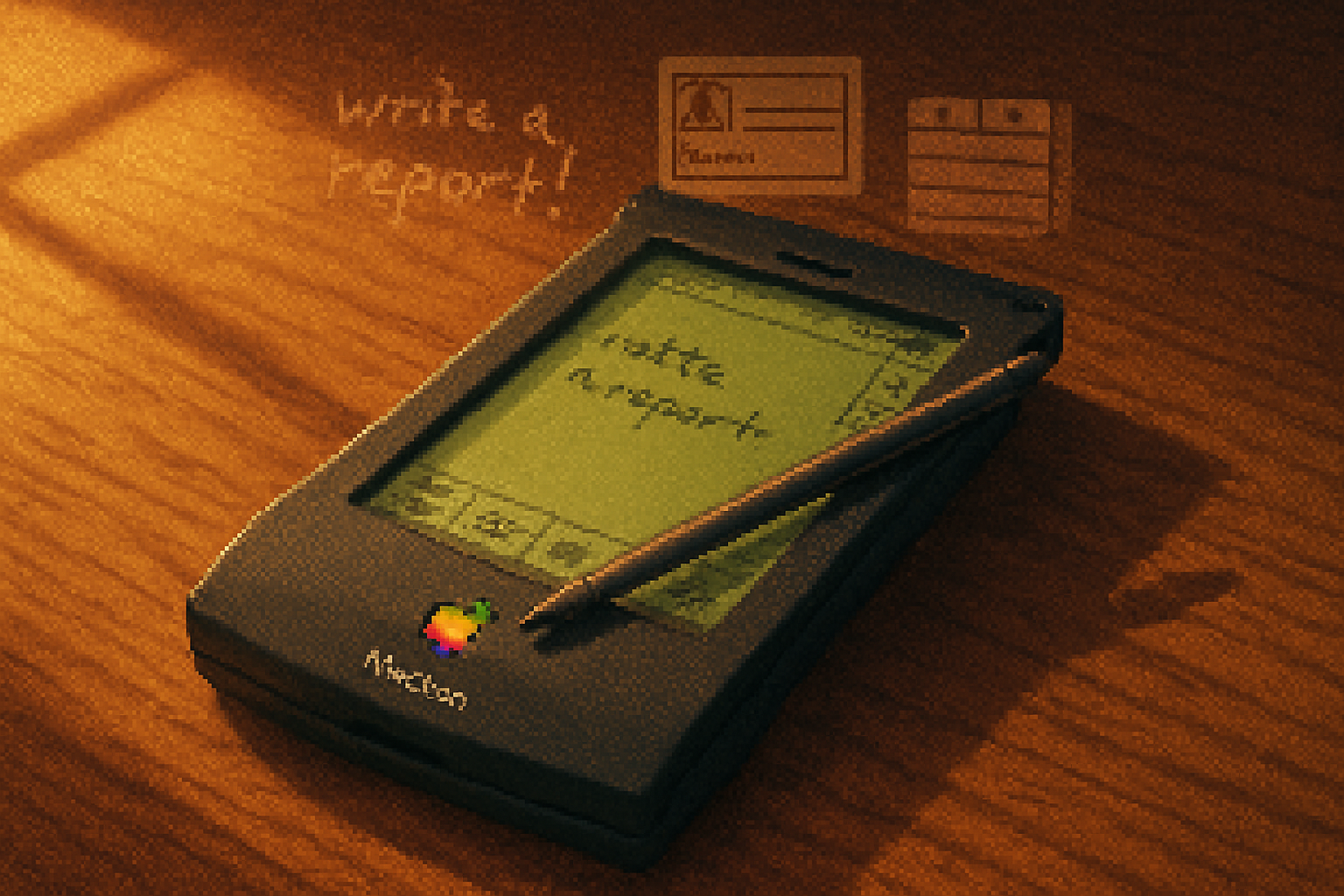

Imagine a mid-1990s office. A manager reaches into a leather bag and produces a slab the size of a paperback, taps it with a stubby plastic stylus and - to the astonishment of onlookers - writes a note that the machine understands. That’s the picture Apple wanted to sell: a portable, personal assistant that could read handwriting, organize your life, and fit in a briefcase.

The reality was messier, and more interesting.

Why the Newton matters (even if you think it doesn’t)

If you think the iPad appeared out of a Steve Jobs-shaped puff of genius in 2010, you’re indulging in technological amnesia. The Newton MessagePad, introduced in 1993, carried three ideas that now look inevitable:

- A touchscreen-first personal computer for everyday people.

- Natural input via handwriting and a stylus.

- An app-centric device with a bespoke operating system designed for mobile constraints.

These were not small choices. They reframed what a computer could be: less a desk-bound calculation engine and more a bedside, handbag, or briefcase companion.

(For a quick overview of its lineage, see the Newton entry on Wikipedia.)[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apple_Newton]

The clever bits: what Newton actually got right

Handwriting recognition - ambitious and fallible

Newton’s headline feature was its ability to accept handwriting and turn it into typed text. The idea was simple in pitch and fiendishly hard in practice: read messy human marks the way a human would. That feature made Newton a rare mix of hardware and AI ambition in a palmtop.

It got better over time. Developers and Apple refined the recognition engines, and later devices were notably more accurate. But early high-profile errors - live demos where a neat note turned into gibberish - made for easy ridicule in the press and late-night TV. The lesson was blunt: pioneering a new input method invites public humiliation as a cost of progress.

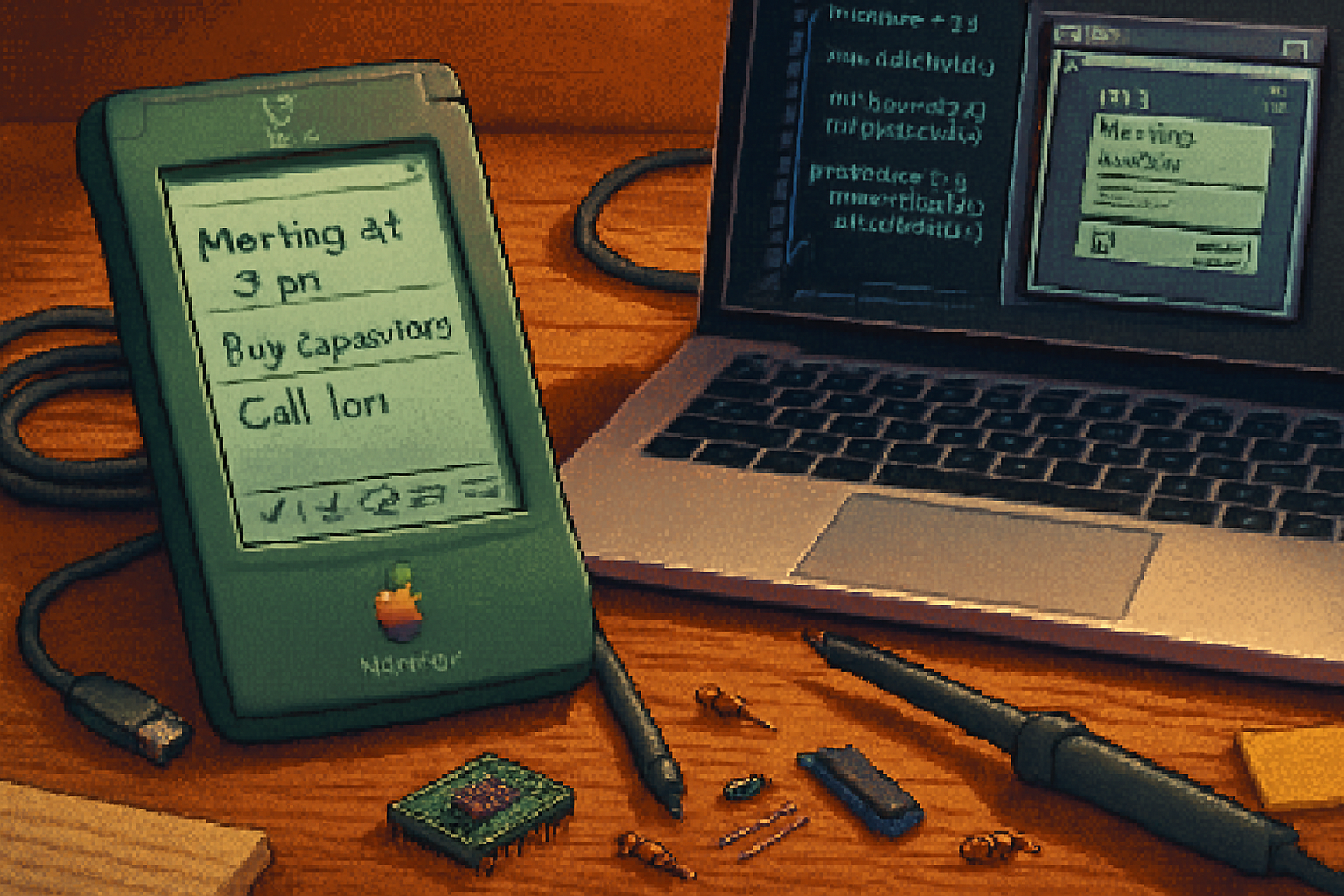

A real operating system for small devices

Newton ran Newton OS, a bespoke environment with its own object-oriented language (NewtonScript) and a design that treated RAM and battery as precious commodities. Rather than shoehorning desktop paradigms into a tiny device, Newton OS tried to invent new metaphors: handwriting fields that knew context, a notes application, a simple messaging/address book, and apps designed specifically for interrupted, mobile use.

NewtonScript, in particular, was a forward-looking experiment: a language optimized for dynamic objects and for devices that could not afford heavy runtimes. That lineage - small, efficient runtimes designed for constrained devices - is visible in many later mobile platforms.

Form factor and stylus-driven UX

The MessagePad family (MessagePad 100, 110, 120, 130, 2000 and others) and the education-oriented eMate 300 showed that Apple was experimenting with size, keyboard attachments, and stylus input long before tablets found their modern silhouette. Accessories, docking stations, and handwriting templates suggested a device that could be both personal and embedded into workflows.

The failures: why Newton became a punchline

The Newton is often remembered as a blockbuster flop. That memory is fair, but incomplete. Its problems were mostly practical rather than conceptual:

- Early handwriting recognition mistakes were widely publicized, turning a visionary feature into a joke.

- Hardware was expensive and battery life was limited by contemporary components.

- The device arrived into a fragmented market of PDAs, palmtops, and laptops; consumers didn’t yet have a clear reason to replace their paper and to-do lists.

- Apple’s own turmoil in the mid-90s - management upheaval and strategic drift - prevented the Newton from getting the consistent stewardship it needed.

In 1998, as part of a company-wide streamlining after Steve Jobs returned, Apple discontinued Newton product lines and shifted focus toward core Mac strategy.

(For a readable history of its rise and fall, Ars Technica’s retrospective remains useful.)[https://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2013/01/the-apple-newton-how-the-original-tablet-almost-succeeded/]

What Newton taught the world - seven concrete legacies

- Tablets are about input, not just display. Newton argued that if we change how people give information to machines - from keyboard to handwriting - we can change what the machines do for us.

- Handwriting as an interface is not dead. Modern iPads support Apple Pencil and “Scribble” handwriting-to-text features; Samsung’s S-Pen lineage is a direct descendant of the stylus idea.

- Mobile-first OS design matters. Newton OS showed you can design an operating system around interruptions, limited memory, and sporadic connectivity - lessons mobile OS makers later internalized.

- Developer ecosystems win. Newton’s limited third-party app ecosystem illustrated that hardware alone can’t make a platform; you need developers and a means to reach users.

- Live demos can make or break public perception. The Newton learned the hard way that early-stage AI features can create lasting reputational damage if showcased prematurely.

- Prototypes teach future product teams what to copy and what to avoid. Many Newton concepts were recycled, improved, and reintroduced decades later more successfully.

- The idea can outlast the product. Even after discontinuation, Newton influenced designers and engineers who moved on to new projects.

A quick catalogue: the most notable Newton models

- MessagePad 100/110/120 (early consumer devices) - introduced handwriting and the concept.

- MessagePad 2000/2100 (later, bulkier, powerful models) - attempted to be a power user device.

- eMate 300 (1997) - a child- and classroom-oriented laptop-shaped device with built-in keyboard and longer battery life.

Each model represents an iteration in Apple’s thinking about who might use such a device and how.

The irony of Jobs and the stylus

When Apple reintroduced the concept of a modern tablet with the iPad in 2010, the company did so without a stylus. Steve Jobs had famously mocked styluses in his iPhone launch: “Who wants a stylus?” The irony is delicious: the Newton had leaned into a stylus, while Apple later insisted touch should be finger-first.

But the story doesn’t end in doctrinal purity. Apple later embraced the Apple Pencil for iPad Pro, acknowledging that for certain tasks - drawing, handwriting, detailed markup - a pen is the better tool. Newton’s stubborn insistence that a pen could be the primary interface was not wrong so much as premature.

(See Steve Jobs’ 2007 comments on styluses as a notable turning point.)[https://www.macworld.com/article/1067543/iphone_keynote.html]

Why the Newton deserves empathy, not mockery

It’s easy to lampoon machines that fail in public. But consider this: the Newton attempted to convert messy, human handwriting into structured data on a 4–6 MHz processor with memory measured in megabytes. It did so decades before the sweeping improvements in storage, compute, and machine learning that make modern handwriting recognition almost effortless.

That combination of human-centered ambition and technical limitations is exactly what defines many foundational technologies. The Manhattan Project failed many times before succeeding; the Wright brothers crashed frequently before staying aloft. Newton is in that family of earnest, necessary failures that educate entire industries.

How Newton’s DNA shows up in devices you use today

- Handwritten notes on tablets (Scribble on iPadOS, note apps that convert handwriting).

- The stylus as a specialized tool (Apple Pencil, Samsung S-Pen).

- App-focused small devices with bespoke OSes (iOS, Android) - mobile-first design, app stores, sandboxing.

- Elegant syncing of contacts and calendars across devices - Newton helped normalize thinking about personal information as something you carry, not something tied to a single machine.

Final verdict: ancestor, not villain

The Newton MessagePad is less a footnote and more a fossil: evidence of an evolutionary branch that taught later designers what to keep and what to refine. Its handwriting recognition misfires gave the industry a cautionary tale about public demos. Its guts - an OS crafted for constrained hardware, a pen-first input model, and a nascent app ecosystem - seeded ideas that reemerged when hardware and networks caught up.

Crucially, the Newton forces us to see technological progress as iterative and human. Visionary design frequently arrives before the rest of the stack is ready: networks, batteries, silicon, developer communities. When the world finally catches up, the idea looks inevitable. When it arrives too early, it gets lampooned and shelved.

The Newton deserved better reviews, and it deserved the goodwill that later devices enjoyed. But it also earned its place in the genealogy of tablets. The next time you pull a pencil-shaped stylus from beside your tablet, take a small, private moment of gratitude for a bulky, stylus-wielding slab that tried, bravely and noisily, to teach computers how to read our handwriting.

References

- Apple Newton - Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apple_Newton

- Smithsonian National Museum of American History - Newton MessagePad (object record): https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_1184378

- Ars Technica - The Apple Newton - how the original tablet almost succeeded:

- Macworld - iPhone keynote transcript (Jobs, 2007): https://www.macworld.com/article/1067543/iphone_keynote.html