· retrotech · 5 min read

The Legacy of Xanga: Lessons in Online Community Building

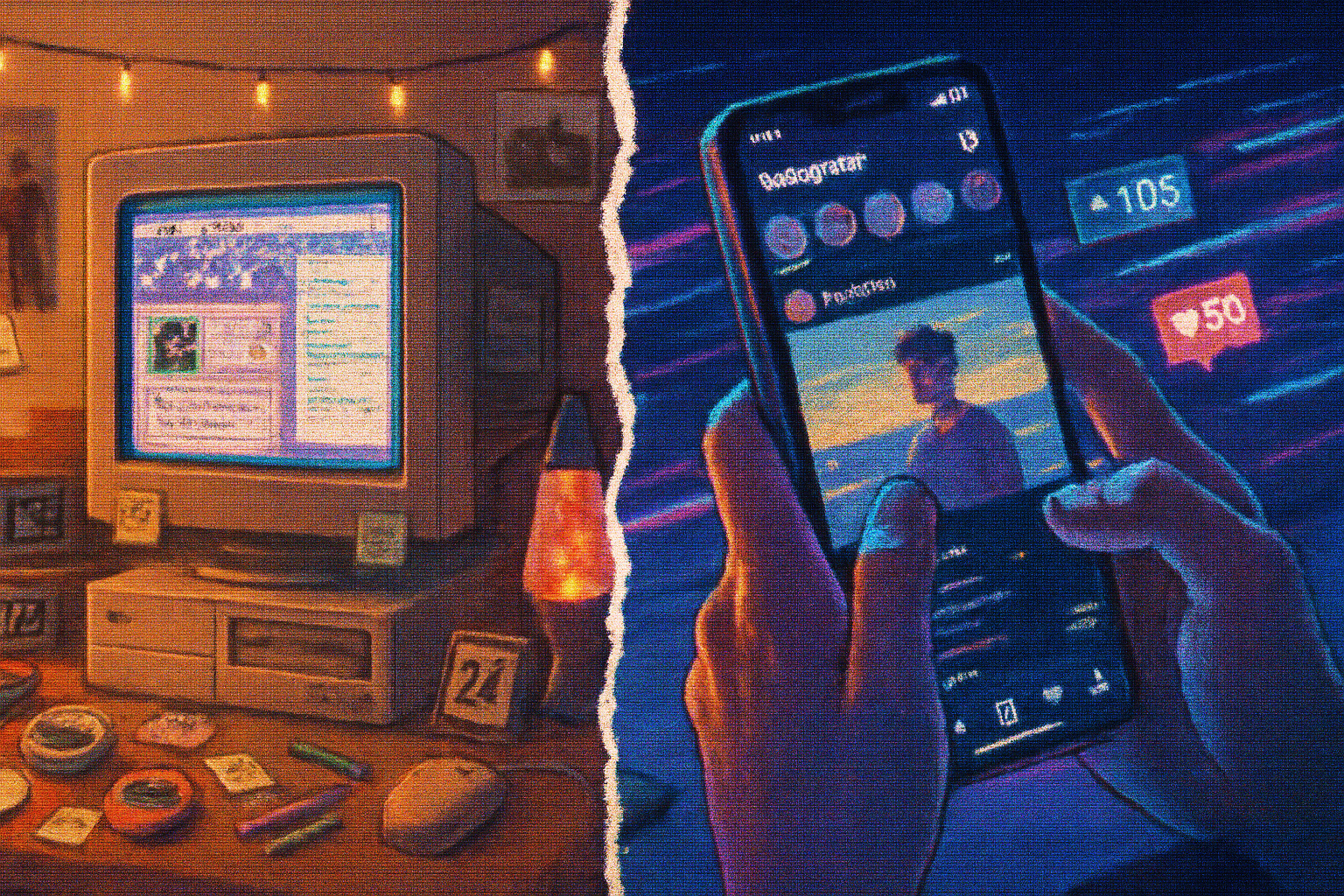

Xanga wasn't just a blogging platform - it was an incubator of intimacy, small-scale civic rituals, and the idea that social software could be both personal and public. This essay examines what Xanga got right (and wrong) and extracts practical lessons for today’s platforms, from attention design to archival stewardship.

I signed up for a blog platform in my teens because that was what people did when they were trying to be interesting and incognito at the same time. The page loaded slowly, the graphic header was proudly terrible, and a handful of friends left comments that read like private letters published publicly. It felt like a tiny town where everyone knew your aliases and your favorite song.

That small-town intimacy is what made platforms like Xanga more than a technology: they were social practices, a set of rituals and expectations that guided how people showed up online. Xanga’s story is partly nostalgic and partly instructive. For anyone building the next generation of social software, it’s a case study in how product choices shape social life.

A quick sketch: what Xanga actually was

Xanga occupied a corner of the early 2000s internet where personal publishing met friend networks. It wasn’t the biggest platform; it didn’t have the fortunes of a later Facebook or the scale of YouTube. It did something more modest and, in retrospect, more interesting: it made it easy to write, decorate, and maintain an ongoing personal space where friends could visit, comment, and leave traces.

For context and timelines, see the Xanga overview on Wikipedia and archived front pages preserved by the Internet Archive.

The human mechanics that mattered

Beneath the pixelated layouts and glittery banners, Xanga hosted a set of social affordances that turned users into communities:

- Intimacy over spectacle. Profiles were written as if for people who already knew you. That lowered the bar for vulnerability and increased trust.

- Persistent, discoverable archives. Posts were retained; old posts were navigable. Your past was not ephemeral noise, it was material.

- Friends lists and comment threads. The friend list was a social map; comment threads were group conversations attached to a timeline.

- Rituals and norms. Posting a weekly update, responding to a survey meme, or leaving a “first comment” were small rituals that produced belonging.

These affordances are subtle. They’re not features that scale automatically; they are habits that a product can help cultivate or destroy.

What Xanga teaches modern platforms

Modern social products are mostly built around attention maximization, algorithmic feeds, and scalable ad mechanics. Xanga offers a contrarian set of lessons - not because it was a perfect model, but because its choices foregrounded social life rather than engagement metrics.

1) Design for slow sociality, not instant virality

Virality feels powerful. Slow sociality is durable. Platforms that reward the quick scroll encourage shallow attention and disposable interactions. Xanga’s emphasis on long-form posts and friend-based discovery made relationships cumulative.

Actionable takeaway: give people spaces where conversations can accrue meaning over weeks and years - threaded comments, persistent edits, and stable URLs encourage depth.

2) Rituals beat gamification

Xanga succeeded where many modern apps fail because it cultivated rituals (weekly posts, memes, shared formats). Rituals create predictable return behavior without dangling points or streaks.

Actionable takeaway: design tools for cultural practices - templated post types, shared probes, collaborative lists - rather than shallow reward systems.

3) Make archives a first-class product

Giving users export tools and clear archival policies treats their histories as assets, not liabilities. When platforms erase or entrench content arbitrarily, trust collapses.

Actionable takeaway: offer robust export/import, clear retention policies, and user-facing archival UIs.

4) Enable partial identity and context

Xanga users often cultivated personas that were neither fully anonymous nor insistently branded. That greyland let people experiment with intimacy.

Actionable takeaway: support pseudonymous profiles, flexible privacy settings, and audience controls that let people choose contextual visibility.

5) Prioritize small networks and social graphs

The friend list was Xanga’s social unit. It wasn’t optimized for maximizing degrees of separation; it was optimized for local density - the people who commented and remembered your past.

Actionable takeaway: encourage small, overlapping social circles (sub-communities, micro-groups) as first-class social units.

6) Normalize norms and governance tools

Xanga’s governance was informal, community-driven, and brittle. That’s a cautionary tale: rules arise organically but platforms must scaffold them with policy, moderation tools, and clear escalation practices.

Actionable takeaway: provide transparent moderation paths, community moderation tools, and ways for norms to become codified without crushing spontaneity.

7) Be careful with monetization that fractures trust

When platforms suddenly lock features behind paywalls or pivot business models, communities can fracture quickly. Xanga’s later commercial choices alienated parts of its core.

Actionable takeaway: if you monetize, do it in ways that preserve the communal fabric - subscriptions for creators that don’t remove communal affordances, optional features rather than whole-platform gates.

Concrete product ideas inspired by Xanga

- “Neighborhoods” - opt-in, persistent micro-communities visible to a chosen friends list.

- Personal archives with timeline playback - let users walk visitors through a curated history of their posts.

- Ritual templates - weekly prompt packs that groups can adopt, creating shared customs.

- Export-as-package - one-click export of your profile, posts, and comments to an interoperable format.

- Pseudonym lanes - allow accounts to hold multiple persona pages with separate follower lists.

Where Xanga misstepped (and how to avoid it)

No platform is a paragon. Xanga’s strengths came with costs:

- Fragile scale - small communities are precious but vulnerable to churn.

- Limited content moderation - early-era norms didn’t anticipate scale problems.

- Business instability - users depend on platforms; platform pivots can be ruinous.

Avoiding these pitfalls means pairing the social design that creates intimacy with robust institutional safeguards: clear moderation, sustainable monetization, and migration paths.

A final, slightly moral point

We like to imagine the early web as an Eden of authentic connection - nostalgia softens everything. But Xanga’s value wasn’t mystical. It was baked into concrete design choices: archives retained, comments threaded, friends visible, rituals encouraged. Those are not expensive features; they are acts of intent.

If you are building a community, you are not merely shipping code. You are curating a place where people will be bored, furious, tender, flirtatious, and outraged. Design for those lives. Design for the slow accrual of memory. Design for the fact that human beings keep their receipts.

References

- Xanga - Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xanga

- Internet Archive - Xanga snapshots: https://web.archive.org/web/*/xanga.com

- LiveJournal and Myspace for contemporaneous context: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/LiveJournal, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Myspace