· retrotech · 6 min read

The Legacy of Windows Write: A Nostalgic Dive into Early Word Processing

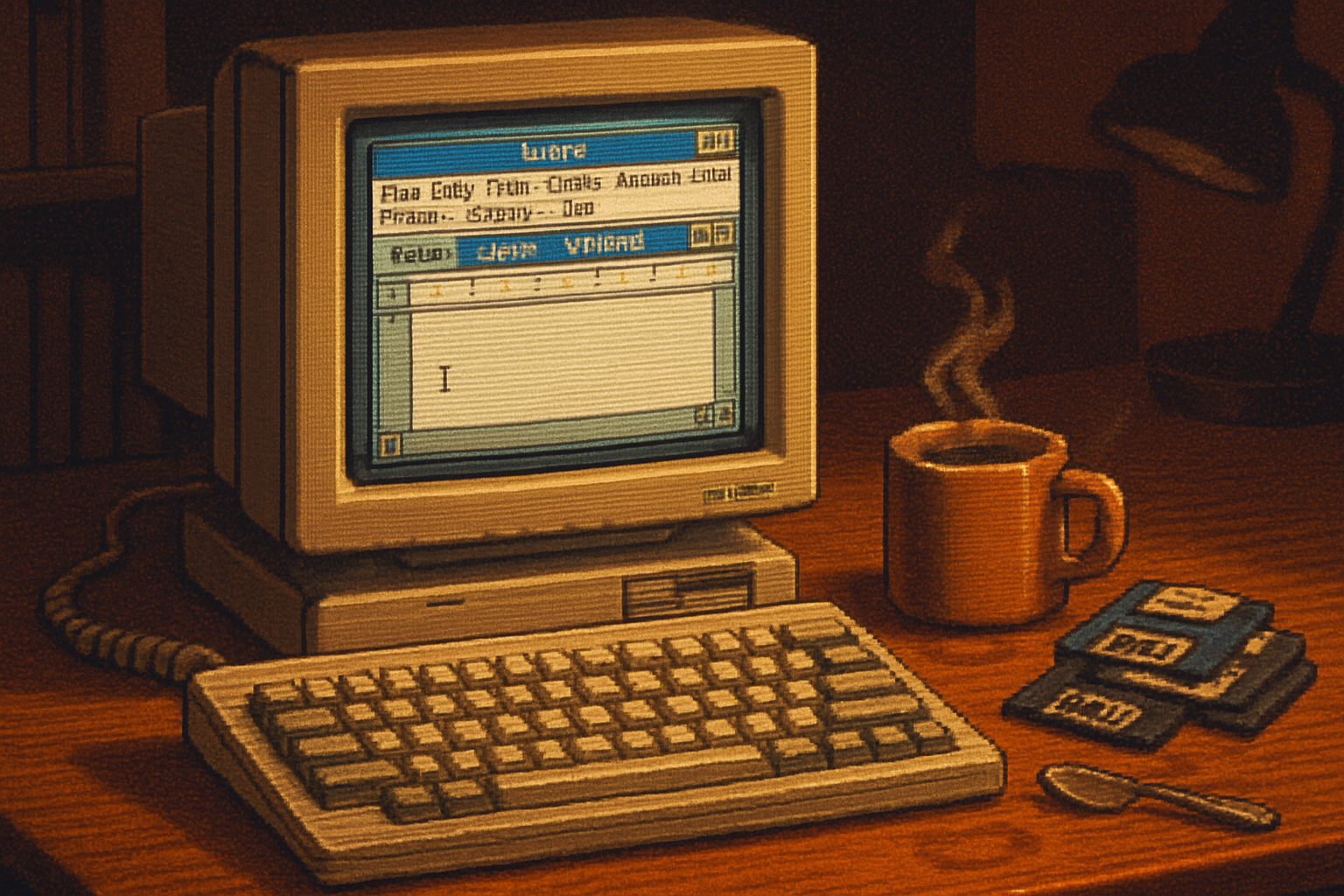

A look back at Windows Write - the simple word processor bundled with early Windows - its role in shaping user expectations, file formats and UI patterns, and why it still sparks nostalgia among early PC users.

A small program with a big memory

If you used a PC in the late 1980s or early 1990s, there’s a good chance you remember opening a plain window, clicking a simple menu and typing words into a clean, unadorned page. That program was often Write (sometimes called Microsoft Write) - the basic word processor that came with early versions of Microsoft Windows. It was never billed as a rival to WordPerfect or Microsoft Word, but it mattered in ways that still ripple through modern software.

This post takes a nostalgic but analytical look at Write: what it was, why people remember it fondly, and how early constraints and design choices from applications like Write helped shape the modern word processing and UI landscape.

What was Windows Write?

Write was the lightweight word processor bundled with early versions of Microsoft Windows. It provided the kinds of features Windows users needed for simple documents: formatted text, font selection, paragraph alignment and basic printing. It launched in the era when graphical user interfaces were still new to many PC users and made text creation feel approachable to people who had previously worked in DOS text editors.

Key points:

- Write appeared in early Windows releases and persisted through several 16-bit Windows versions before being superseded by WordPad in later Windows releases.

- Documents created by Write commonly used the .wri file extension.

- It intentionally traded advanced features for simplicity and low resource use - important on machines with limited RAM and single-digit megahertz processors.

For more on its placement in Windows history, see the Write and WordPad pages on Wikipedia: Write (Windows) and WordPad.

Why Write felt important to users

There are practical and emotional reasons Write left an impression:

Speed and immediacy - On sluggish hardware, a lightweight editor that launched quickly and let you start typing right away felt liberating. No boot into DOS, no command-line flags - just a window and a blinking cursor.

Low friction - The UI was pared down to essentials. Menus were short, controls were familiar. For many users this was their first experience with a graphical text editor and the concepts of fonts, proportional spacing and WYSIWYG (what you see is what you get).

A stepping stone - For home users, students and office workers who didn’t need mail-merge macros or advanced typesetting, Write was “good enough.” It lowered the barrier to producing readable, formatted documents.

Nostalgia - The look and sound of old Windows - the grey windows, the bitmap fonts, the click of early GUI controls - trigger powerful memories. People remember Write not just as a tool but as a part of learning to use a computer.

Design choices that mattered

Early software is interesting because it was designed under strict constraints. Those constraints forced choices that, in hindsight, influenced modern apps.

Minimal UI and task focus - Memory and CPU limits rewarded minimalism. Write’s UI emphasized the document and basic editing, a pattern we still follow in “distraction-free” editors and the simplified mobile document viewers many users prefer today.

Shared UI primitives - Write used the same menu structures, dialog boxes and color/font pickers as other Windows apps. This encouraged a consistent mental model for users - a foundational idea behind platform-based UX guidelines.

File-format pragmatism - To be useful across a variety of applications and versions, early Windows applications often relied on simple or well-documented formats. While Write used its own format (.wri), the era’s experimentation with rich-text representations contributed to later standards such as RTF, which became an important interchange format for rich-text documents.

Immediate printability - The direct print path and expectation that what you saw on screen should resemble the printed page pushed developers to pay attention to device contexts, font metrics and layout - early groundwork for the fidelity users expect from modern document rendering.

From Write to WordPad to rich cloud editors

Write didn’t try to win the feature race. As Windows matured and hardware improved, Microsoft introduced WordPad - a successor that offered richer text-handling (and used the Rich Text Format) - and heavyweight word processors like Word continued to add features for professional users.

The trajectory from Write to WordPad to full-featured desktop suites and finally to cloud-based editors (Google Docs, Office Online) shows a steady expansion of what a “document” can be: collaboration, versioning, embedded media, live fonts and platform-independent rendering. Yet the basic expectations established by early tools - immediate startup, visible formatting, reliable printing - persisted.

Lessons for modern software designers

Studying Write and its contemporaries offers practical lessons:

Design for constraints - Small, focused apps often win users for everyday tasks. Optimize for speed and clarity rather than feature bloat.

Make basic tasks trivial - The discovery of core features (save, print, change font) should be immediate. Early users learned the power of GUIs because apps made the basics simple.

Keep platform conventions consistent - Reusing native controls builds user confidence and reduces learning overhead.

Provide sensible defaults and fallback formats - Interoperability matters. Early experimentation with document formats paved the way for RTF and later standardized formats.

Why the nostalgia matters

Nostalgia isn’t just sentimentality; it reveals what users value. When people fondly recall Write, they often cite:

- A feeling of empowerment - Their first typed letter, homework, resume or school report.

- Simplicity - An uncluttered interface that didn’t get in the way.

- Reliability - Software that did its job without surprises on limited hardware.

Those feelings help explain why many modern apps aim for clarity and low friction - designers are trying to recreate the same approachable experience that early tools provided.

A quick timeline

- Mid-1980s - Write ships with early Windows releases as the bundled word processor.

- Early 1990s - Write continues to appear in Windows 3.x. RTF and richer formats gain popularity.

- Mid-1990s - WordPad and other richer editors appear; Write’s role diminishes as Windows evolves.

(For detailed chronology, see the Windows history pages and WordPad documentation.)

Closing thoughts

Windows Write was modest in ambition but significant in impact. It helped teach millions of users what a word processor could be: immediate, visual and approachable. The lessons from its design - keep the essentials accessible, respect platform conventions, and optimize for the realities of your users’ hardware - remain relevant.

If you remember the grey window and the simple toolbar fondly, you’re not alone. Those early experiences shaped how a generation learned to create, edit and share text - and they left design fingerprints we can still detect in the tools we use today.

Further reading

- Write (Windows) - Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Write_(Windows)

- WordPad - Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/WordPad

- A brief history of Microsoft Windows - Microsoft documentation and histories