· culture · 6 min read

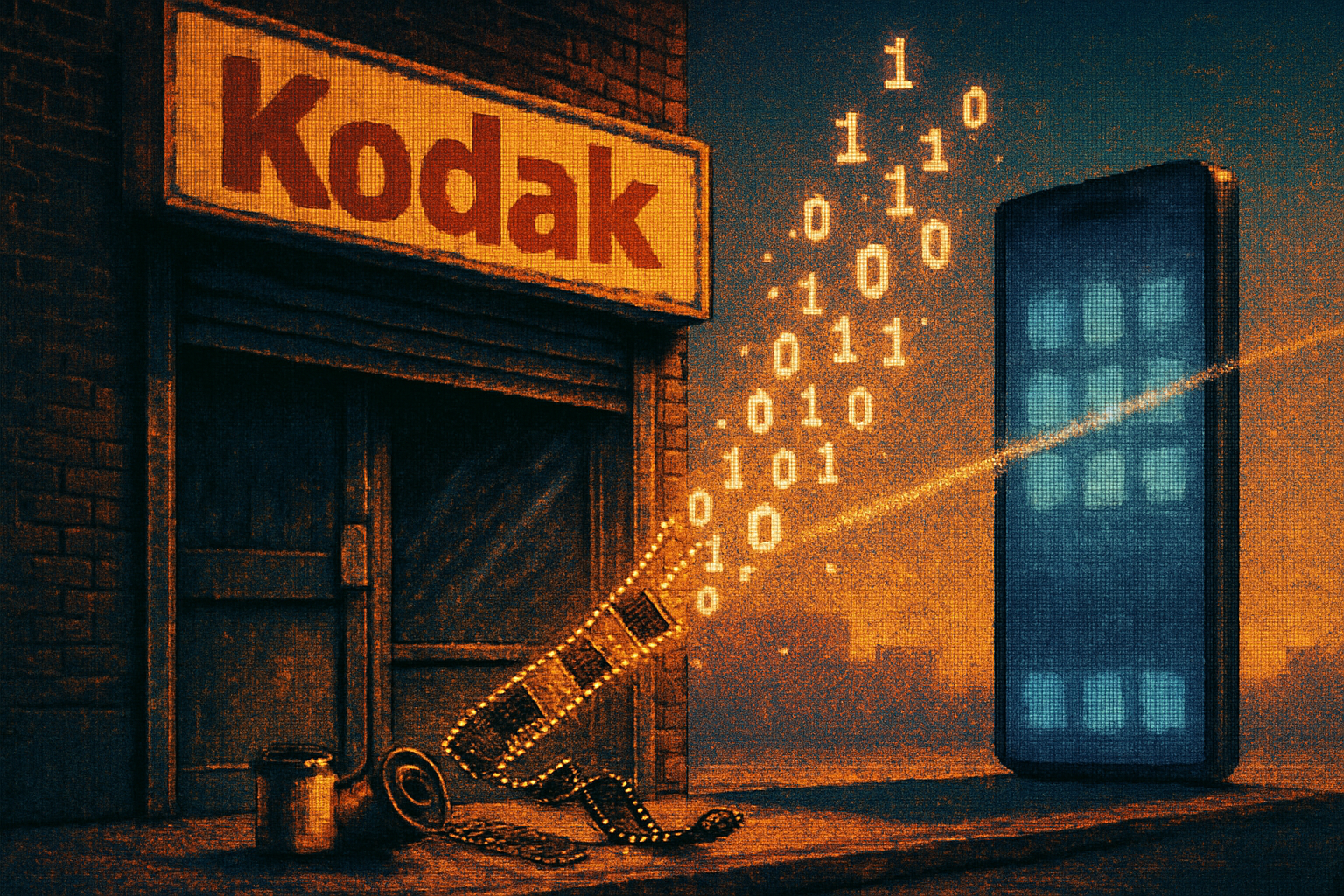

Kodak's Missteps: A Cautionary Tale for Modern Tech Companies

Kodak invented the digital camera, then spent decades protecting film. Its decline is a textbook lesson in how corporate success can calcify into strategic blindness - and what modern tech firms must do to avoid the same fate.

In 1975 an engineer at Kodak lugged a prototype made of tape, a lens and a bulky sensor into a lab and showed it to colleagues. It took 23 seconds to record a black-and-white image. When asked what the thing would do to Kodak’s future, the obvious answer - obliterate it - was politely ignored.

That engineer, Steven Sasson, had built the first digital camera at Kodak. The company that taught the world how to “press the button” and trust a cartridge of chemistry was sitting on a device that would make chemical processes quaint. The rest, as they say, is history: Kodak would eventually file for bankruptcy in 2012 and emerge a much smaller firm, having missed the wave it helped create Smithsonian NYT.

This is not merely nostalgia. Kodak’s downfall is a concentrated lesson for any modern tech company that grows fat on a dominant product while the landscape quietly remakes itself.

A quick, brutal timeline

- 1888–1970s - Kodak dominates photography with film, cameras and a vertically integrated ecosystem (film, processing, kiosks)

- 1975 - Kodak engineer Steven Sasson builds the first digital camera. The company patents digital imaging but treats it as an internal curiosity rather than a strategic priority

- 1990s–2000s - Kodak invests in digital technology but fears cannibalizing a hugely profitable film business. It pursues slow, incremental digital products while protecting film margins

- 2012 - Kodak files for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, unable to transition fast enough before smartphones and cheaper digital cameras commoditized imaging

What really went wrong (the anatomy of the error)

Kodak didn’t fail because it lacked engineering talent. It failed because strategy, incentives and organizational structure conspired to make rational, short-term choices that were catastrophic long-term decisions.

Protection of a cash cow

Kodak’s film business was enormously profitable. Managers were judged on quarterly and annual film P&L. Anything that eroded film sales - including a superior digital offering - looked like self-sabotage to those managers. This is textbook “protect the incumbent” behavior.

The Innovator’s Dilemma in motion

Clayton Christensen’s thesis - incumbents often lose to disruptive technologies because the new tech initially serves smaller or unattractive markets - played out at Kodak. The early digital camera didn’t look like a profitable replacement for film; executives deprioritized it in favor of incremental improvements to existing products Wikipedia: The Innovator’s Dilemma.

Organizational inertia and internal cannibalization fears

Kodak invented digital imaging but often buried it inside the same structures that made film successful. New ventures were starved of autonomy, resources or P&L independence so they could compete for internal budgets on the same terms as core businesses.

Misreading ecosystems and software

Kodak thought cameras were primarily hardware and chemistry problems. It underestimated the shift toward software, services and ecosystems (photo-sharing platforms, mobile apps, smartphone integration). When the smartphone turned every consumer into a competent photographer, Kodak’s consumer hardware mattered less.

Poor portfolio and option management

Kodak treated technology investments as projects to be justified like capital expenditures, not as optionality that should be nurtured even if initially loss-making. That left it with few meaningful bets when the market shifted.

What managers get wrong when they say “we innovate”

- “We invest in R&D” - but only to improve the cash cow.

- “We have skunkworks” - but the skunkworks report to the same divisional head who owns the old business.

- “We follow the market” - often a euphemism for following revenue, not change.

Kodak ticked these boxes. The language of innovation was used as window dressing while the real decisions preserved the existing economic model.

Lessons for modern tech companies (do these, not that)

If you run a large tech firm today, Kodak’s corpse should be a warning lamp on your dashboard. Here’s a practical playbook:

Create independent, full-P&L units for disruptive bets

- If a new technology could reduce revenue for your flagship product, don’t force it to fight with that product under the same boss. Give it autonomy.

Accept controlled cannibalization

- Encourage product teams to launch offerings that can replace existing ones. Reward leaders for long-term migration success, not short-term retention of legacy sales.

Measure learning as a KPI

- Not every bet will pay off. Make measured bets and evaluate them on the speed of validated learning, not just near-term revenue.

Embrace platform thinking and software-first design

- Hardware without a service or software moat is an easily commoditized asset. Think ecosystems - how does the product improve with every additional user?

Run red-team scenarios and pre-mortems

- Force teams to create credible worst-case scenarios where the core product becomes obsolete, then design contingency pivots.

Keep option-value capital available

- Don’t fence off all capital to the most profitable product. Reserve a portfolio of exploratory R&D that can be scaled if conditions change.

Hire cognitive diversity and institutionalize dissent

- Create formal mechanisms for contradicting the dominant narrative. Incentivize internal adversaries to be candid.

Focus on platform lock-in and recurring revenue

- Kodak sold moments. Modern firms sell access, services and data flows - recurring models survive disruption better.

Tactical checklist (a 9-point war room starter)

- Inventory - list every tech/feature that could degrade your flagship’s core revenue.

- P&L separation - create separate financial statements for disruptive experiments.

- Cannibalization policy - pre-approve frameworks that let teams cannibalize legacy revenue under controlled metrics.

- Learning dashboards - build metrics for hypothesis testing and learning velocity.

- Ecosystem mapping - chart your product’s place in user workflows and adjacent networks.

- Acquisition vs. incubation rules - decide when to buy an insurgent and when to build one inside.

- Scenario drills - run pre-mortems quarterly on “what if our main product is replaced.”

- Incentive realignment - tie exec compensation to long-term migration, not short-term profits alone.

- Communication playbook - when pivoting, own the narrative - be honest about why cannibalization is necessary.

Counterexamples worth studying

- Netflix cannibalized its DVD business with streaming, choosing to destroy a strong revenue source to win a bigger market. That decision required brave leadership and tolerance for short-term pain.

- Apple pivoted from personal computers to a tightly integrated hardware+software+services ecosystem, which made it resilient against commoditization.

These companies didn’t have perfect foresight. They had the courage to favor future value over present comfort.

Closing image (a lesson in humility)

Kodak was not stupid. It made rational choices within a set of incentives that rewarded preservation. The tragedy is how ordinary those choices were: a dozen executives making defensible, conservative calls that added up to strategic ruin.

If you lead a modern tech company, imagine your flagship product as a magnificent horse. You can polish the saddle and feed the horse more oats - or you can notice the highway full of cars. Loving the horse is fine. But worshiping it is a managerial failure.

Kodak’s story is not a morality play about hubris versus virtue. It is a procedural manual of what normal corporate behavior looks like when disruption arrives. Read it, internalize it, then design your organization to behave un-normally when the world changes.

Sources and further reading

- On the first digital camera and Steven Sasson - Smithsonian Magazine -

- Kodak bankruptcy coverage - The New York Times -

- Analysis of Kodak’s strategic errors - Bloomberg -

- Context on Kodak’s corporate history - Britannica -

- Christensen’s framework (Innovator’s Dilemma): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Innovator%27s_Dilemma

- Wired on Kodak’s invention and neglect of the digital camera: https://www.wired.com/2012/01/kodak-digital-camera-invention/