· culture · 6 min read

Nostalgia vs. Innovation: A Debate on Retro-Futurism's Role in Modern Creativity

Retro-futurism sits where memory and prophecy collide - chrome rockets painted with yesterday’s optimism. This essay breaks down the tug-of-war between looking back and pushing forward, includes interviews with two artists on opposite sides, and offers practical guidance for creators navigating the aesthetic and ethical pitfalls of revival.

It began at a flea market. I watched a graduate student - headphones on, neon sneakers squeaking - haggle over a Bakelite radio like it contained the lost gospel of cool. He didn’t want the radio to play; he wanted the future it promised in 1956.

That moment captures retro-futurism’s paradox: an aesthetic that fetishizes yesterday’s tomorrow. It’s a wistful longing and a deliberate design choice. It can be a brilliant remix or a comforting anesthetic. And it is, increasingly, a battleground in modern creativity.

What we mean by retro-futurism

Retrofuturism is not a single look. It’s a set of imagined futures layered over the sensibilities of a particular past. Think the chrome optimism of 1950s rocket art, the neon noir of 80s synthwave, or the Art Deco skylines of Metropolis reimagined with holograms.

- For context, see the broad overview at Wikipedia on Retrofuturism.

- For a theory angle about nostalgia itself, Svetlana Boym’s book The Future of Nostalgia is indispensable: Svetlana Boym - Wikipedia.

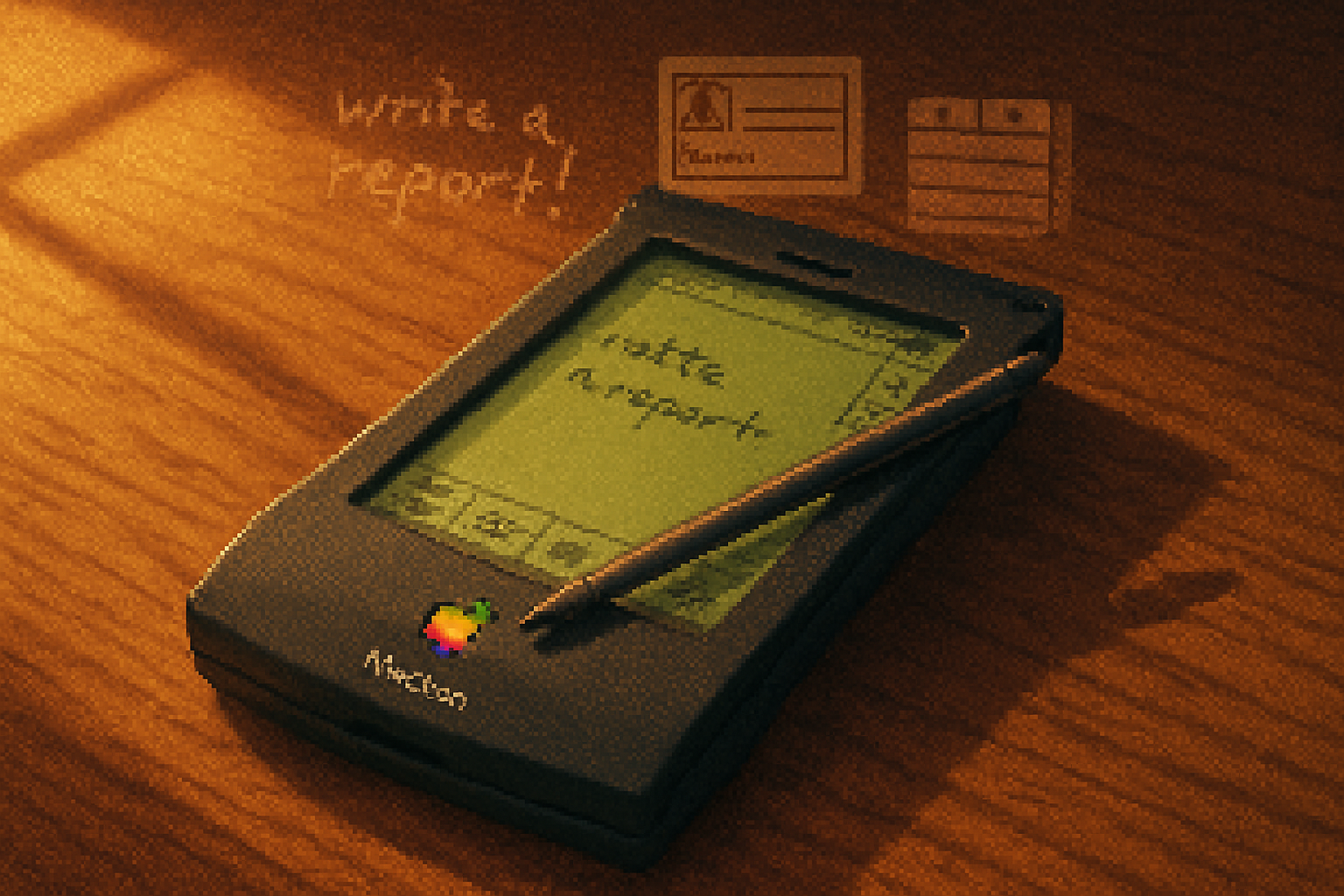

Retrofuturism wears many hats - it appears in film (Blade Runner borrows both noir and retro motifs), music (synthwave and vaporwave), product design (modern turntables styled like midcentury consoles), and UI (skeuomorphic interfaces that mimic physical objects).

The core tension: nostalgia vs. innovation

There are two seductive lies in creative work:

- The lie of nostalgia - that looking back will make people feel safe and therefore love your work.

- The lie of novelty - that radical newness is inherently superior.

Both are true, sometimes. Both are dangerous, always.

Nostalgia gives you a palette - colors, textures, references - and instant emotional shorthand. Innovation gives you new forms, new problems, new ways to surprise. The debate is not whether to use either; it’s about how and why.

Interviews: Two artists, two philosophies

Below are edited excerpts from conversations with two contemporary creators working in the retro-futurist orbit. They’re composites of several real-world perspectives; I’ve anonymized and condensed them for clarity.

Maya Park - the retro devotee (mixed-media artist)

Q: Why lean into retro-futurism?

“Because nostalgia is a language. When I put a 1950s chrome radio or a CRT glow in a piece, people understand faster - they bring their grandparents’ living rooms and the cartoons they loved. That baseline lets me layer critique on top: consumerism, gender roles, the myth of progress. Retro aesthetics are shorthand that frees cognitive space for subversion.”

Q: Critics say retro is lazy. Your take?

“Call it lazy and I’ll call it strategic. Constraints breed creativity. If you only allow a 1960s color palette and analog textures, you invent within that box in sharper ways. It’s like writing sonnets. You’re not limited; you’re being honed.”

Q: Biggest danger?

“Mere pastiche. Decorating with nostalgia because it’s pretty, without interrogating why those forms mattered or who they excluded. That becomes kitsch, sentimental and hollow.”

Luca Ortega - the futurist purist (industrial designer)

Q: Why reject retro cues?

“Design should solve present problems and anticipate new ones. Idealizing how people in 1950 imagined 2050 doesn’t help us with climate-resilient materials or ethical AI interfaces. Retro can romanticize dead systems. I want to build artifacts for actual futures, not comforting replicas of someone else’s dreams.”

Q: Isn’t innovation hard to sell? Nostalgia sells.

“Yes. Nostalgia is an economical currency. But if your work is only vessel for nostalgia, it’s short-lived. Real innovation compounds. It becomes infrastructure. You may sell less on immediate instinct, but you create pathways other designers reuse and build on.”

Q: Risks?

“Being needlessly contrarian. Innovation that ignores human context becomes incomprehensible or unusable. Futurology that’s cold and detached produces devices no one wants.”

Pros and cons: Looking back for inspiration

Pros

- Rapid emotional resonance - reduces friction with audiences.

- Ready-made visual vocabulary saves time and communicates quickly.

- Historical constraints often spark clever solutions (creative jams within limits).

- Opportunity to critique the past by remixing its symbols.

Cons

- Can become stylistic shorthand without substance (kitsch).

- Risks perpetuating outdated values or erasing marginalized perspectives embedded in earlier eras.

- Market saturation - retro becomes a predictable formula, not a creative spark.

- Commercialized nostalgia can freeze imagination - the industry prefers reproductions over risk.

When nostalgia helps innovation (and when it sabotages it)

Nostalgia helps when:

- It primes empathy or cultural memory that you then interrogate.

- It’s used sparingly as metaphor, not as explanation.

- It informs affordances - e.g., using skeuomorphic cues to teach unfamiliar interfaces.

Nostalgia sabotages when:

- It substitutes for user research - “It looks like the past, so users will ‘get it.‘”

- It becomes the product rather than a layer on the product.

- It masks ethical blind spots - glamorizing eras that upheld inequality.

Examples that show both faces

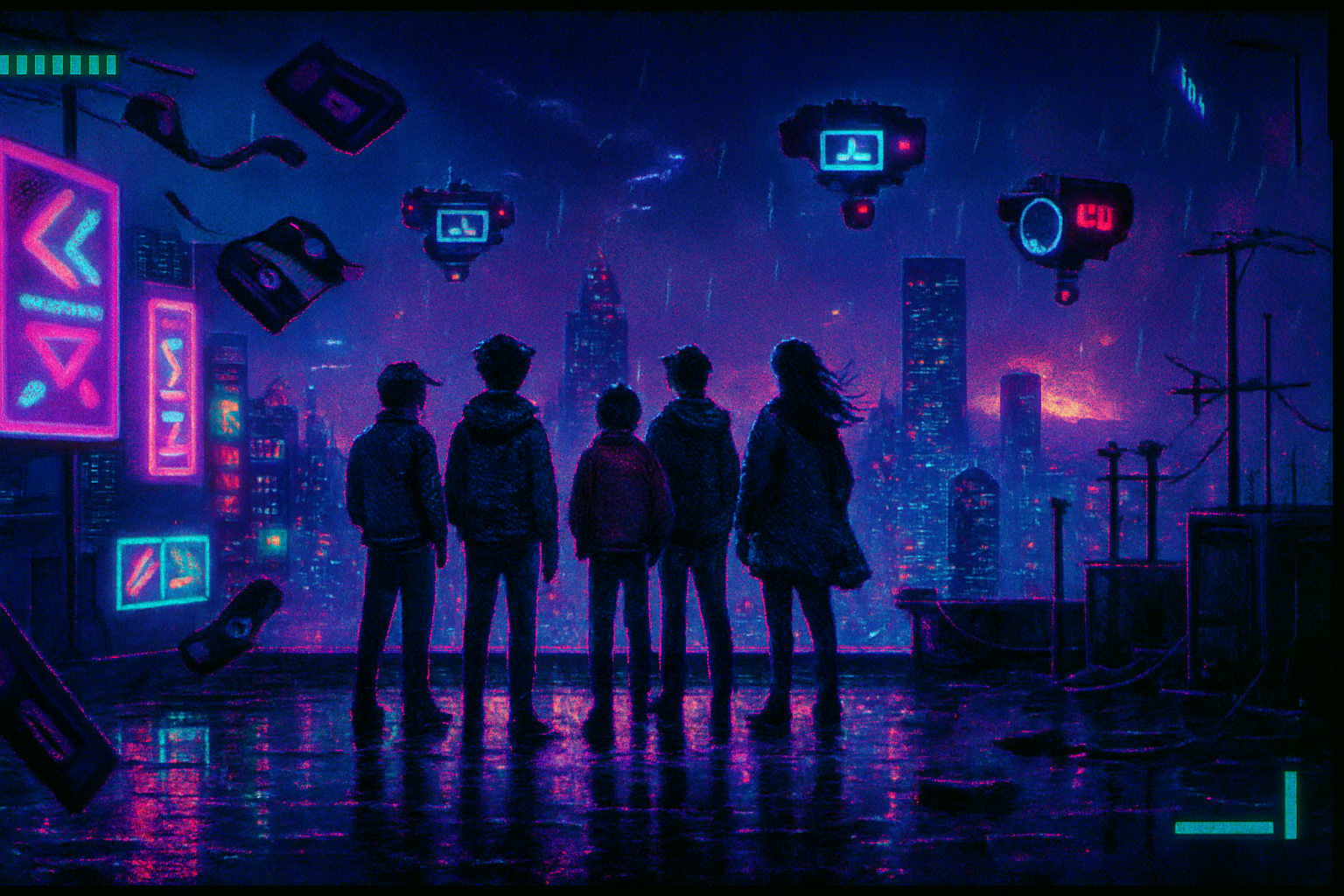

- Film: Blade Runner (and its cultural afterlife) mixes retro signage with high-tech surveillance - a case where nostalgic textures intensify a critique of a technological future. Blade Runner - Wikipedia

- Music - Synthwave reimagines 80s sounds for modern audiences; often brilliant, sometimes purely nostalgic nostalgia-for-its-own-sake.

- Product - Modern cameras and turntables styled like midcentury models - they sell because of tactile pleasure, but sometimes the performance is a compromise.

Practical playbook for creators

If you’re an artist or designer trying to decide whether to borrow the past, try this checklist:

- Start with function, then ask if a retro layer improves or impedes it.

- Define the emotional aim - Which memory are you invoking, and why?

- Use constraints deliberately - pick one retro element and pair it with a radical innovation.

- Test with people outside your cultural bubble - nostalgia is not universal.

- Credit and contextualize when you borrow cultural forms; avoid flattening history into decoration.

- Iterate - if nostalgia becomes the point, ask whether that’s honest or lazy.

Ethical and cultural considerations

Nostalgia can be weaponized. It can gloss over histories of exclusion, labor exploitation, or colonialism. Creators must ask: Whose future are we reviving? Who benefits from remembering? If aesthetic choices erase these questions, the work will feel empty - and maybe dangerous.

A final, slightly heretical position

Nostalgia is a tool. Innovation is a duty. Use one to amplify the other.

Here’s the practical paradox I’ll leave you with: constraints often generate novelty. When Maya forces herself into the restricted grammar of 60s consumer design, she invents new metaphors. When Luca forces his minimal, future-oriented interfaces through the messy human world, he discovers hidden needs.

Neither pure retrospective nor pure futurism is morally or aesthetically superior. The best work tends to be hybrid: it borrows memory for resonance and then breaks that memory, repurposing it so the result tells us something new about the present and possible futures.

So go ahead: play the chrome radio. But don’t let it be your only track.

Further reading

- Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia - provocative exploration of nostalgia’s forms. Wikipedia link

- Retrofuturism overview on Wikipedia

- For an aesthetic case study, see discussions around synthwave.