· culture · 6 min read

The Fallout of Nostalgia: How 80s and 90s Dystopian Visions Are Influencing Today’s Generations

How neon-soaked visions from the 1980s and 1990s - from cyberpunk noir to post-apocalyptic road movies - have been retooled for a generation confronting climate collapse, precarious economies, and surveillance social media. This piece traces the aesthetic and psychological through-lines, explains why these stories resonate, and considers their political and personal consequences.

A teenager in a thrift store holds a cracked VHS of Blade Runner and, a little sheepishly, asks an older clerk if it’s a comedy. The clerk laughs - not at the kid, but at the idea that those grim, rain-drenched futures were ever meant to be funny.

That exchange encapsulates something odd about our moment: the pop-cultural products of the 1980s and 1990s - neon, duct-taped leather jackets, synth soundtracks, bleak cityscapes - are back in vogue. Not just as aesthetic candy. They have returned as a lingua franca of anxiety: stylized, seductive, and oddly consoling.

This essay tracks that return. We’ll look at the roots of 80s/90s dystopian imagination, why its tropes fit perfectly with today’s anxieties about climate, economics, and social media, and what it means for a generation raised on nostalgia-tinged dread.

Where the nightmares came from

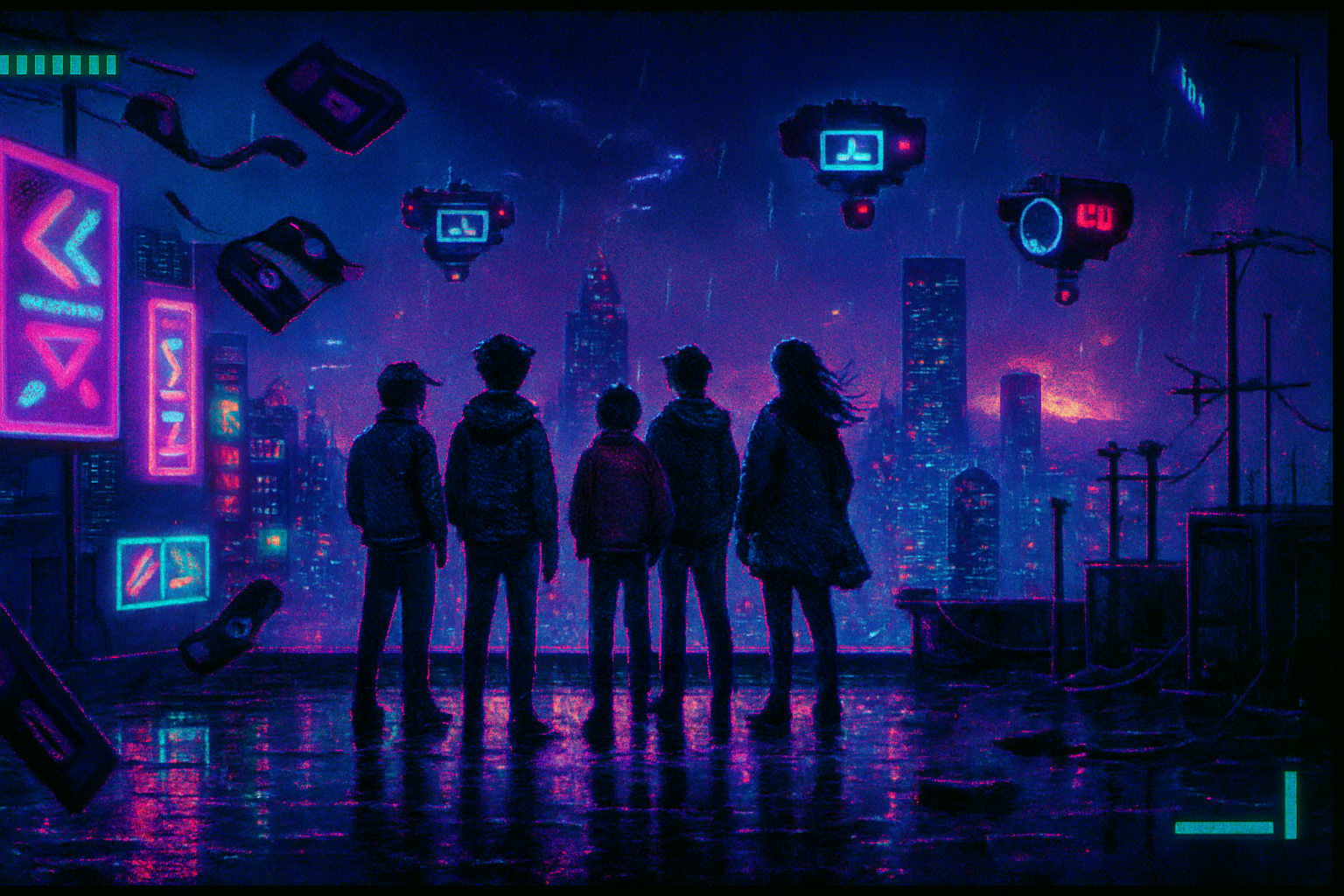

The late Cold War decades produced a distinct strain of speculative fiction: high-tech noir, bioapocalypse, and the forlorn road-movie. Think neon rain in Blade Runner, the fuel-starved deserts of The Road Warrior, the homicidal machines of The Terminator, and the fed-up bureaucratic satire of Brazil. In literature, cyberpunk - William Gibson’s Neuromancer chief among them - gave us a style where capitalism had been electrified into a new mythology.

Those works weren’t merely bleak for shock value. They were, in part, a reaction to rapid technological change, the erosion of familiar institutions, and economic dislocation. They imagined futures in which human dignity and agency were squeezed by corporate power, anonymous systems, and environmental collapse.

The aesthetics came back - and multiplied

Fast-forward. The 2010s and early 2020s saw a twofold renaissance. On one level came pure nostalgia: shows like Stranger Things recycled 80s kitsch (walkie-talkies, malls, Mulder-like sensibilities) into mainstream gold. On another level, the darker half of those decades - cyberpunk and post-apocalypse - mutated into new forms: synthwave music, vaporwave visuals, and video games like Cyberpunk 2077 polished the 80s/90s palette and made it aspirational.

Meanwhile, narrative dystopia itself proliferated. YA franchises like The Hunger Games turned adolescent alienation into blockbuster politics. Television shows such as Black Mirror updated the techno-dread for an always-connected age. The old nightmares were repackaged - shinier, bingeable, and algorithmically recommended.

Why those old nightmares fit today’s fears

Nostalgia is often written off as a soft emotion: syrupy, comforting. But when the past is a brand for present dread, nostalgia becomes a vector. There are three big reasons 80s/90s dystopian tropes resonate now.

Climate as slow-motion apocalypse. The 80s and 90s offered apocalyptic shorthand - nuclear winter, ruined highways, poisoned skies. Those images were allegory then; they’re documentation now. The scientific consensus on climate impacts is tightening the knot of anxiety among young people - the experience of impending, systemic loss maps neatly onto the aesthetics of environmental collapse. (See UNICEF on how climate touches children’s rights and futures:

Economic precarity and fractured social contracts. The late 20th century anxieties about deindustrialization and corporate power have been realized and amplified by precarious work, gig economies, student-debt burdens, and housing crises. The dystopian economy in a film - a city of late-night ads and gated enclaves - no longer feels like fantasy because many young adults experience its outlines firsthand.

Social media as a surveillance apparatus and vector of meaninglessness. The most chilling 80s/90s works imagined systems that watched you, catalogued you, and traded your life for profit. Today, platforms do this in earnest. If you want a conceptual bridge between cyberpunk and modern life, read The Age of Surveillance Capitalism by Shoshana Zuboff. The result: a generation raised on feeds, notifications, and attention markets recognizes the nervous systems those early fictions tried to warn about.

The psychology: why dread is comforting

This sounds perverse. But dystopia feels oddly reassuring in hard times. Why? Because dystopian stories provide a grammar for anxiety. They name threats, show trajectories, and (often) offer resistance. When reality is chaotic and amorphous, a coherent nightmare is preferable. It gives agency: if you can recognize the monster, maybe you can fight it.

There is empirical evidence that extreme climate worry affects mental health. The American Psychological Association and other organizations have documented climate-related anxiety and stress responses - a real, generational grief that dystopian narratives help narrativize (see APA’s 2017 coverage on climate and mental health: https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2017/03/climate-change-mental-health).

Cultural effects: politics, activism, and cynicism

The consequences are mixed.

Fuel for activism. Dystopia can be a call to action. Images of ruined cities radicalize; they give urgency to climate movements, mutual aid projects, and anti-surveillance organizing. The costume of mourning becomes a uniform for protest.

Politics of resignation. Conversely, constant immersion in bleak futures breeds fatalism. If collapse is inevitable, why bother voting? Why invest in long-term community building? That resignation is a political victory for those who profit from passivity.

Aestheticizing suffering. There’s a thin line between using dystopian imagery to critique systems and aestheticizing trauma. Vaporwave and synthwave can make the grotesque look pretty. That’s emotionally efficient-but ethically fraught.

How the narratives get transmitted

These stories don’t just appear spontaneously. There are several transmission mechanisms at work:

- Platforms and algorithms that amplify the familiar - remake, repackage, repeat.

- Marketing and merch that convert dread into revenue (neon jackets and collectible VHS boxes are easier to monetize than policy change).

- Education and community storytelling - zines, online forums, and streaming fan cultures keep the mythos alive and evolving.

What to do about it: practical moves for people and institutions

If the past’s nightmares are shaping the present’s moods, we can either be trapped by them or use them deliberately.

For individuals:

- Translate anxiety into action. Join a local climate group, support tenant unions, or volunteer for civic projects. Narrative gives direction; action gives agency.

- Limit doom scrolling. Dystopia is contagious when consumed in endless loops. Curate your intake.

- Seek collective rituals that aren’t just performance - mutual aid is both practical and healing.

For creators and institutions:

- Tell stories with moral clarity. Dystopia is potent when it clarifies culpability and points to alternatives.

- Avoid aestheticizing suffering without consequence. If you depict collapse, give space to rebuilding.

- Fund media literacy. Teach how algorithms amplify fear and how to read representations critically.

The final reckoning

Nostalgia brought the 80s and 90s back to life because those decades had learned to dramatize the anxieties of technological and economic upheaval. Today’s youth inherit both the style and the substance of those stories - their visuals, their narrative grammar, and their emotional cadences.

That inheritance is double-edged. It can radicalize, galvanize, and clarify. It can also anesthetize, aestheticize, and paralyze. The crucial task is to keep the stories from doing the thinking for us.

Look at the kid with the VHS again. The laugh from the clerk can be warm or scornful. The better response is to hand the tape back and ask: what are we going to do tonight to make the future less like that film and more like something we might actually want to live in?