· culture · 6 min read

Retro Tech and Dystopia: How 80s and 90s Predictions Shaped Modern Anxiety

How the neon nightmares of 80s and 90s fiction - from cyberpunk novels to VHS-era films - encoded a set of fears that now look eerily prescient: corporate power, ubiquitous surveillance, algorithmic opacity, and computerized warfare. Those old anxieties mutated into modern dread about AI, data extraction, and cybercrime.

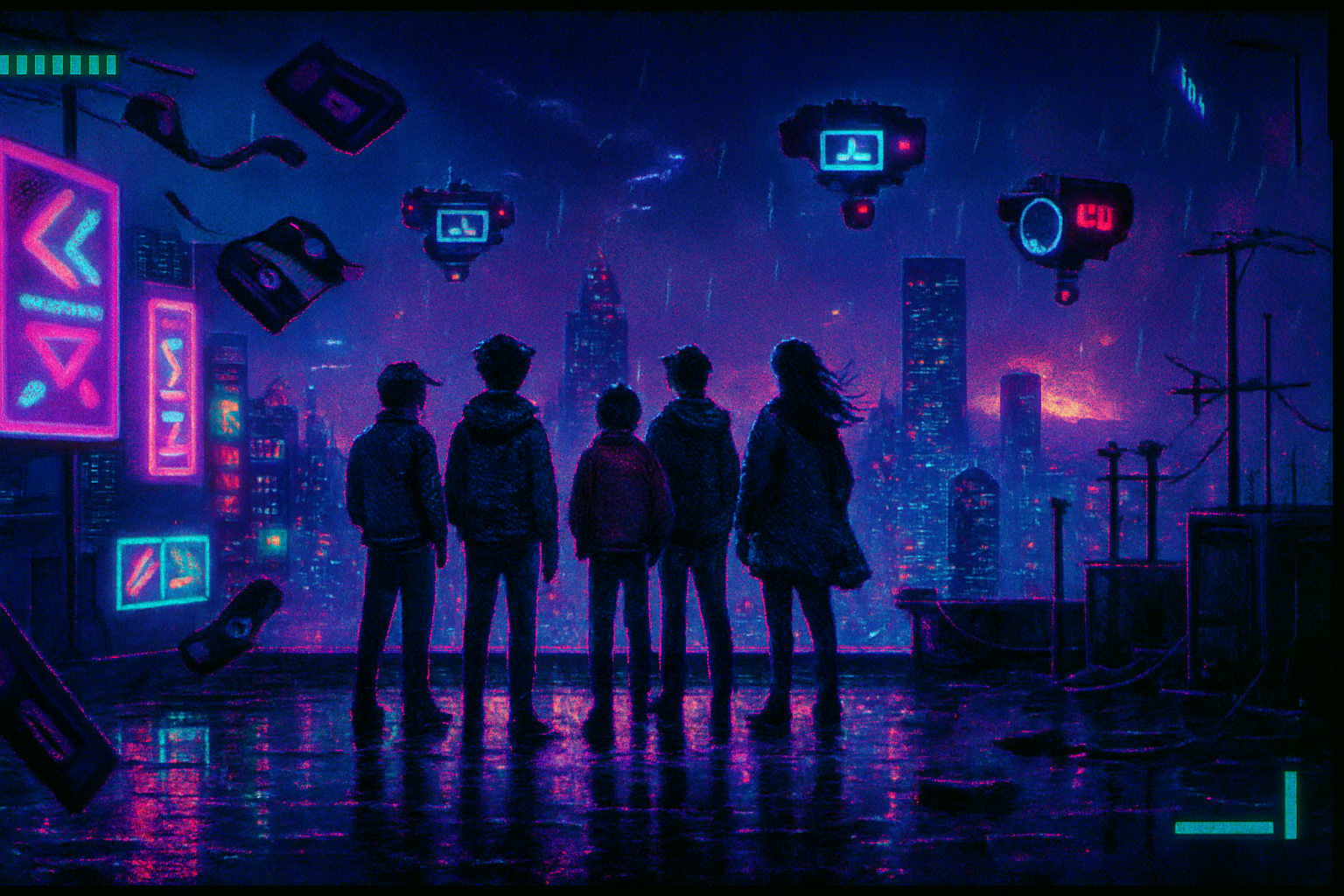

A kid in a flannel jacket once watched a grainy VHS tape of Blade Runner in a single-parent apartment and decided the future would smell of rain and oil. That child graduated into an economy where your movements are priced, your thoughts are predicted, and the rain is still in the forecast. The joke - if you can call it that - is that the prophecy arrived wearing a different logo.

The image that haunted a generation

Retro dystopias were never about gadgets for their own sake. They were about power: who has it, who loses it, and what happens when the machines that mediate that power are designed to amplify inequality. In the 1980s and 1990s a set of recurring images and motifs crystallized in pop culture and literature:

- Neon-lit megacities with gargantuan corporate logos (Blade Runner).

- Networks that feel like other worlds - Gibson’s cyberspace in Neuromancer.1

- Hacked lives and identity theft in films like The Net and Hackers.2

- Autonomous violence and militarized machines (the Terminator franchise).

- Media saturation and corporate messaging run amok (the proto-satire Max Headroom).

These were not mere style exercises. They were allegories for the social and economic transformations then under way: globalization, the rise of transnational corporations, an early internet that promised liberation but delivered new concentrations of power.

What the retro prophets feared - in plain language

The fears encoded in 80s/90s dystopias can be grouped into a few blunt categories:

- Surveillance made banal. Not just eyes in the sky, but systems that convert attention into data. The fear - you become infra-red on a corporate dashboard.

- Corporate sovereignty. Mega-corporations that behave like nation-states, answerable to shareholders rather than citizens.

- Loss of agency through networks. Hackers, viruses, and inscrutable systems that rewrite the rules of identity and consent.

- Autonomous violence. Machines that decide who lives, who dies, and why a handshake is now an algorithm.

Those were metaphors dressed up in techno-fetishism. But metaphors matter. They teach publics what to fear.

From VHS to real-world headlines: the slow march of plausibility

Fiction can feel quaint until reality catches up. Three case studies show the trajectory from cinematic dread to headline-making anxiety.

Mass surveillance - For decades, popular culture imagined ubiquitous observation. That imagination hardened into policy when Edward Snowden exposed mass, indiscriminate intelligence collection in 2013, revealing programs that tracked metadata and communications on a planetary scale.

Data extraction and influence - The 90s fear of stolen identity mutated into a 2010s nightmare when firms commodified attention and behavioral data. The Cambridge Analytica scandal made explicit the capacity to profile, microtarget, and nudge political opinions using harvested social-media data.

Algorithmic opacity and AI - What started as sci‑fi speculation about sentient machines has become a series of more mundane yet insidious problems: opaque decision-making systems for lending, hiring, policing, and content moderation. These systems don’t need malice to be harmful; they only need biases baked into data and incentives that favor scale over fairness.

Each of these is less a single monster and more a networked ecosystem of technologies, institutions, and habits that together shape what citizens experience as normal.

Why the retro aesthetic still matters (and why it misleads)

Retro dystopia persists for two contradictory reasons.

First, it offers an emotional shorthand. Neon + rain = market failure and moral rot. That shorthand helps people understand complex systems quickly.

Second, retro tech provides a scapegoat. It’s comforting to believe a single technology is to blame. It’s tidier than admitting that centuries of political and economic choices - deregulation, underfunded institutions, market incentives - sculpted these outcomes.

So the retro story is half-true. The aesthetics predict the mood of modern anxiety but misattribute causation when they imply that refrigerators, VHS, or early modems are the root cause. They are the vectors - the carriers - not the origin.

How old fears mutated into new ones

The DNA is recognizable. The form has evolved.

Surveillance is now algorithmic and commercial. It’s not only the state watching; it’s companies profitably predicting your next purchase, partner, or protest sign. See Shoshana Zuboff’s account of “surveillance capitalism.”3

Hacking used to mean a raw, countercultural joyride. Today it includes sophisticated cybercrime, supply-chain compromises, election interference, and ransomware that can cripple hospitals and pipelines.

Autonomous systems were cinematic killswitches. Today they’re utilities and administrative tools that quietly displace judgment - credit scoring, parole algorithms, content-ranking systems - with consequences that fall unevenly on the vulnerable.

This mutation has a name: normalization. Once-spectacular fears become background noise until something catastrophic wakes us up - and then we go back to sleep.

The human cost: trust, attention, and civic capacity

The concrete consequences are easy to miss when you fetishize gadgets. But they are real:

- Erosion of trust. When systems are opaque and platforms are optimized for engagement and ad revenue, trust in institutions declines.

- Attention scarcity. The economy of attention reconfigures politics; rage is profitable, nuance is not.

- Civic fragility. Democracies require shared facts and mutual plausibility. When data becomes weaponized, the social fabric frays.

Put another way: retro dystopias warned us that the machinery of modern life could be turned against us. The machinery was sold as convenience. The danger is that convenience became a structural condition.

Not all dystopia is inevitable: what to do next

If the lesson of retro dystopia is grim, the remedy is not theological. It is political, legal, technical, and cultural. Some realistic levers:

- Regulation that targets incentives. Fix the profit motives that reward attention extraction and opaque automation. Consider stronger data-protection regimes and algorithmic transparency mandates.

- Public infrastructure for trust. Fund independent auditing bodies, public-interest data repositories, and civic APIs that give citizens control over public services.

- Design ethics by default. Build systems that value human dignity and auditability over maximum engagement.

- Literacy and narratives. Teach citizens how these systems work - not just via manuals but through stories and cultural artifacts that show how power imbalances feel in daily life.

These are not magical fixes. They are the earnest, bureaucratic work of shaping institutions so technology serves liberty rather than undermines it.

A final, unromantic truth

The kids who watched Blade Runner didn’t predict the exact architecture of our modern fears. They did something more important: they taught a generation to be suspicious of big promises wrapped in sleek interfaces.

That’s a useful inheritance. Suspicion without action is mere cynicism. Action without moral imagination is tyranny. The cultural artifacts of the 80s and 90s handed us both: a lens and a warning. The lens helps us see; the warning tells us where to put our effort.

The retro dystopia that once felt like style now feels like a blueprint. The good news - yes, there is good news - is that blueprints can be revised. They are human documents, after all, and all human documents are amenable to amendment.

Footnotes

William Gibson coined the term “cyberspace” in his 1984 novel Neuromancer, a foundational text for cyberpunk imagery. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuromancer ↩

On 1990s films that dramatized networked fear, see Hackers (1995) and The Net (1995): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hackers_(film), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Net_(film) ↩

Shoshana Zuboff’s The Age of Surveillance Capitalism analyzes commercialized surveillance: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Age_of_Surveillance_Capitalism ↩