· retrogaming · 7 min read

From Controversy to Cult: The Most Polarizing Philips CD-i Games

The Philips CD-i promised a multimedia revolution and delivered a handful of games that infuriated Nintendo fans and enchanted later generations. This post examines the most controversial CD-i titles - why they sparked outrage, how they were made, and why they now enjoy a strange, persistent afterlife among retro gamers.

I remember the first time I saw the CD-i Zelda cutscenes: my cousin’s VCR had better acting. The living room went quiet - not because we were impressed, but because we weren’t sure whether we’d just witnessed a game or an avant‑garde puppet show gone wrong.

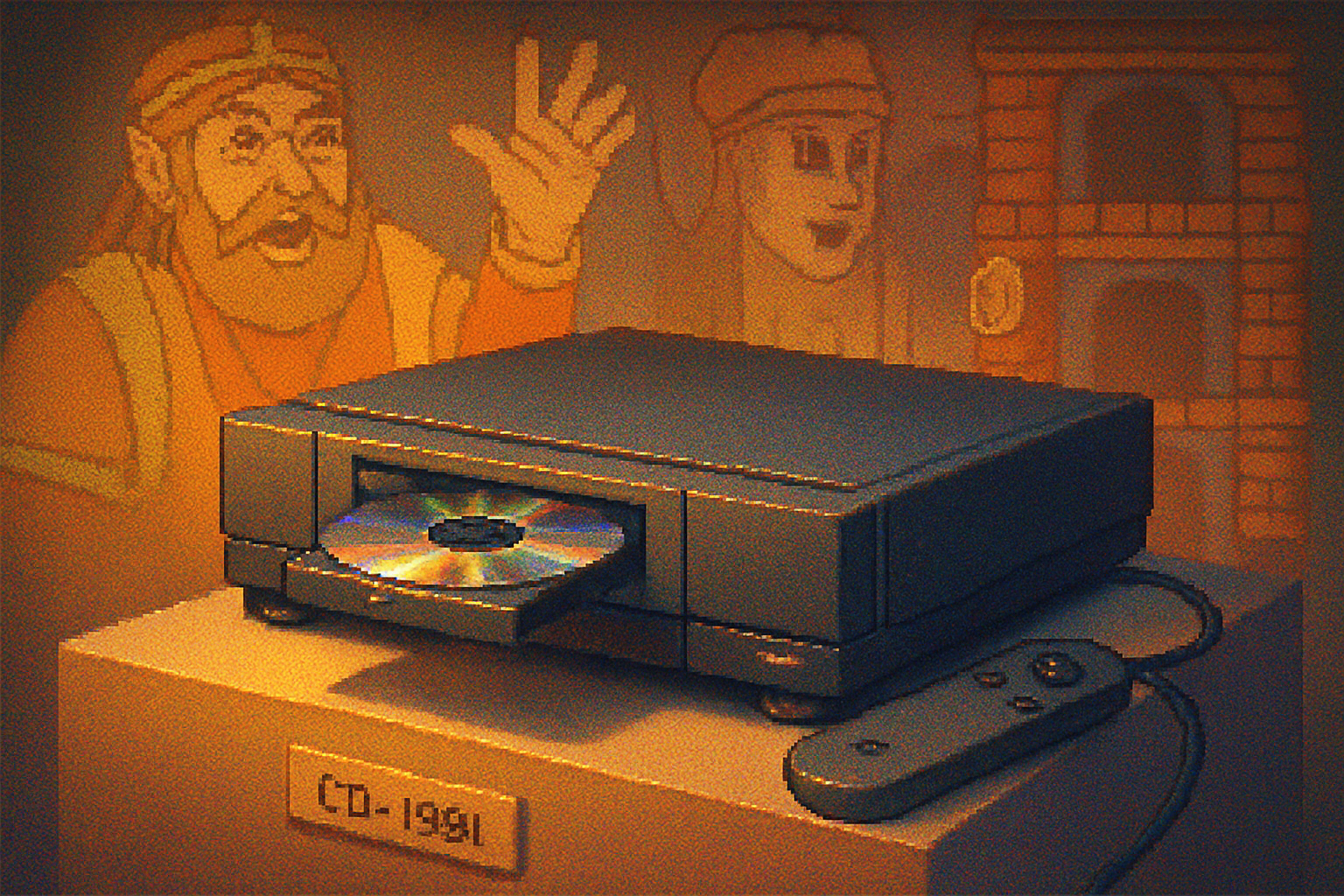

Philips’ Compact Disc Interactive (CD‑i) sits in gaming history like a badly rewritten footnote: ambitious, confused, and impossible to ignore. The system promised “multimedia” dreams - interactive encyclopedias, educational software, and yes, licensed Nintendo characters - but what arrived on store shelves was a ragged mix of earnest experiments and spectacular misfires. Some of those misfires became lightning rods for controversy; decades later they’ve become cult objects, meme fodder, and the subject of earnest attempts at reappraisal.

Why do a handful of Philips CD‑i games still trigger heated debate? The reasons are a braid of legal oddities, creative mismatch, technical constraint, and the peculiar human tendency to love the thing that vexes us. Below I unpack the most polarizing titles, explain the controversies, and ask what they tell us about how we remember (and misremember) the past.

Quick context: how did Nintendo characters end up on a Philips console?

Short version: badly negotiated deals and corporate fumbling.

- In the early 1990s Nintendo explored a CD‑based add‑on for the SNES with Sony. That partnership collapsed. Philips, briefly an alternate partner, later retained rights to use some Nintendo characters for non‑console products as part of the settlement. The result - a handful of legitimately licensed Mario and Zelda games for a system Nintendo didn’t want associated with its brands [

This bureaucratic footnote is crucial. The CD‑i Zelda games and Hotel Mario weren’t bootlegs. They were authorized. Which only made the disconnect between Nintendo’s brand and the CD‑i’s execution sting more.

Most polarizing CD‑i titles

Below are the games that produced the most heat - whether for being tonally wrong, technically incompetent, or proudly bizarre.

1) Zelda: The Wand of Gamelon (1993)

What it is: A side‑scrolling action game with dozens of hand‑drawn animated cutscenes and full voice acting.

Why it inflamed fans:

- The visuals and voice acting in the cutscenes were widely mocked for awkward animation and hammy delivery.

- Gameplay is clumsy compared with Nintendo’s Zelda standards - poor collision, slow controls, and a structure that feels foreign to what players expected from the franchise.

- It carried the Zelda name but not the Zelda sensibility. Fans felt the tone betrayed the series’ DNA.

Retrospective take:

- Meme fuel - lines and expressions from its cutscenes are staples in “so‑bad‑it’s‑good” collections. See the infamous animation studio work in multiple YouTube compilations and retrospectives.

- Cultural artifact - some historians and fans now treat it as an object lesson in licensing, brand mismatch, and early ’90s multimedia aesthetics [

2) Link: The Faces of Evil (1993)

What it is: A companion side‑scrolling CD‑i Zelda game, made by the same team and sharing the same oddball cutscene style.

Why it inflamed fans:

- It doubled down on the failings of Wand of Gamelon - story beats that misread Link’s character, awkward animation, and clunky platforming.

- Many players judged it harsher because it was the other half of the pair and therefore confirmed the pattern.

Retrospective take:

- While there’s grudging admiration for the ambition (CD‑i pushed full animation and voice at a time when most games had none), Faces of Evil is usually invoked as an example of how not to handle beloved IP [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Link:_The_Faces_of_Evil].

3) Zelda’s Adventure (1994)

What it is: An isometric adventure with FMV sequences rather than the animated shorts of its siblings.

Why it inflamed fans:

- Technical limitations made the game feel slow and opaque; load times and pixelated FMV didn’t help.

- The title deviated yet again from what Zelda fans expected - it’s a different genre, with baffling puzzles and an awkward perspective.

Retrospective take:

- Slightly kinder reassessment than the side‑scrollers, because it aimed for a more serious tone and attempted a different game design; still largely considered undercooked [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zelda%27s_Adventure].

4) Hotel Mario (1994)

What it is: A Mario puzzler in which each level is a hotel (yes, plumber‑themed hospitality), punctuated by bizarre FMV cutscenes.

Why it inflamed fans:

- Mario’s voice, mannerisms, and the cutscenes felt off-many players found them dissonant and unfaithful to Nintendo’s characterizations.

- Gameplay boiled down to sliding doors and awkward collision detection - not worth the brand name it carried.

Retrospective take:

- Hotel Mario is the other half of the CD‑i’s licensing mystery - it proved beyond doubt that just because you have Mario’s sprite doesn’t mean you have Mario. It’s both detested and beloved - detested for being wrong, beloved for being weird enough to watch repeatedly [

Honorable mentions: Burn:Cycle and FMV experiments

The CD‑i also hosted earnest FMV and multimedia attempts like Burn:Cycle and A Fork in the Tale. Those weren’t controversial in the same outraged, meme‑worthy way as the licensed games, but they divided audiences.

- Some players admired the cinematic ambition and early experiments with interactive movie mechanics.

- Others criticized shallow interactivity and FMV limitations. The result - niche cult followings rather than mainstream infamy.

What made these games controversial - beyond bad acting

Let’s be blunt. The outrage wasn’t simply about ugly pixels and hammy voice acting. There were structural reasons these titles became lightning rods.

- Licensing without stewardship - Nintendo’s characters were used without Nintendo’s usual quality control. That’s branding malpractice.

- Expectation mismatch - fans applied Nintendo standards to games made by teams who had different priorities and fewer resources.

- Technical constraints - the CD‑i was not a purpose‑built game console; it prioritized audio and video playback over tight input responsiveness.

- Cultural timing - the early ’90s was a transitional moment - developers were learning to merge animation, voice, and interactivity. Failures were loud because the medium was experimenting publicly.

These ingredients turned a few mediocre games into cultural incidents.

How critics and gamers view them today

There are two broad camps in 2025: derisive historians and nostalgic archivists.

- The derisive view - These games are examples of hubris - a tech company thinking licensed IP can paper over design and production failures. Critics point to them as cautionary tales about brand dilution.

- The nostalgia/archival view - The CD‑i titles are cultural artifacts that tell us about an era when multimedia meant something different. The cutscenes, strange voice acting, and earnest FMV are studied, remixed, and turned into memes. They’re raw material for nostalgia and videogame folklore.

Across both camps there’s grudging agreement: they’re historically interesting. And that matters. Bad art can still illuminate the decisions, economics, and hubris of its time.

The justice of time: cult, memes, and preservation

Controversy doesn’t die; it transmutes. The CD‑i’s most notorious games migrated from outrage to meme to curated relic. Why?

- The internet loves a trainwreck, especially one with memorable lines and uncanny animation expressions.

- Preservation efforts and retro communities have rescued CD‑i titles from obscurity, making them easier to revisit and reassess.

- Curiosity beats contempt - players eager to see the oddities for themselves became the game’s best marketers.

Play one of these titles in 2025 and you’ll likely smile, cringe, and think. That’s a valuable reaction. It’s engaged. It’s cultural.

What they teach us about licensing and creative control

There’s a thin moral here and it’s not cute: licensing intellectual property is not a substitute for craft. The CD‑i saga shows that:

- Brand guardianship matters. When IP leaves the hands of creators who understand its cultural logic, odd things happen.

- Technical platforms shape creative output. A device built for video will not automatically produce great games.

- Historical artifacts are useful. Even bad or weird media teach us about the economics and aesthetics of their era.

Final thought

If controversy is a bell, the Philips CD‑i games rang it loud. They were not simply bad; they were illustrative - of corporate missteps, of early multimedia bravado, and of how communities turn embarrassment into affection. The CD‑i didn’t kill an industry. But it produced a handful of titles that continue to irritate, amuse, and instruct.

In the end, controversy became a kind of cult. The games are still terrible in the way you expect. And yet - like a misread poem or a badly sung folk song - they get replayed. We watch them not because they’re perfect, but because they show us a moment when the future of games was being fumbled into being.

References

- Philips CD‑i - Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philips_CD-i

- Zelda - The Wand of Gamelon - Wikipedia:

- Link - The Faces of Evil - Wikipedia:

- Zelda’s Adventure - Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zelda%27s_Adventure

- Hotel Mario - Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hotel_Mario

- Polygon retrospective on the CD‑i: https://www.polygon.com/2014/4/11/5591348/philips-cd-i-history