· retrogaming · 7 min read

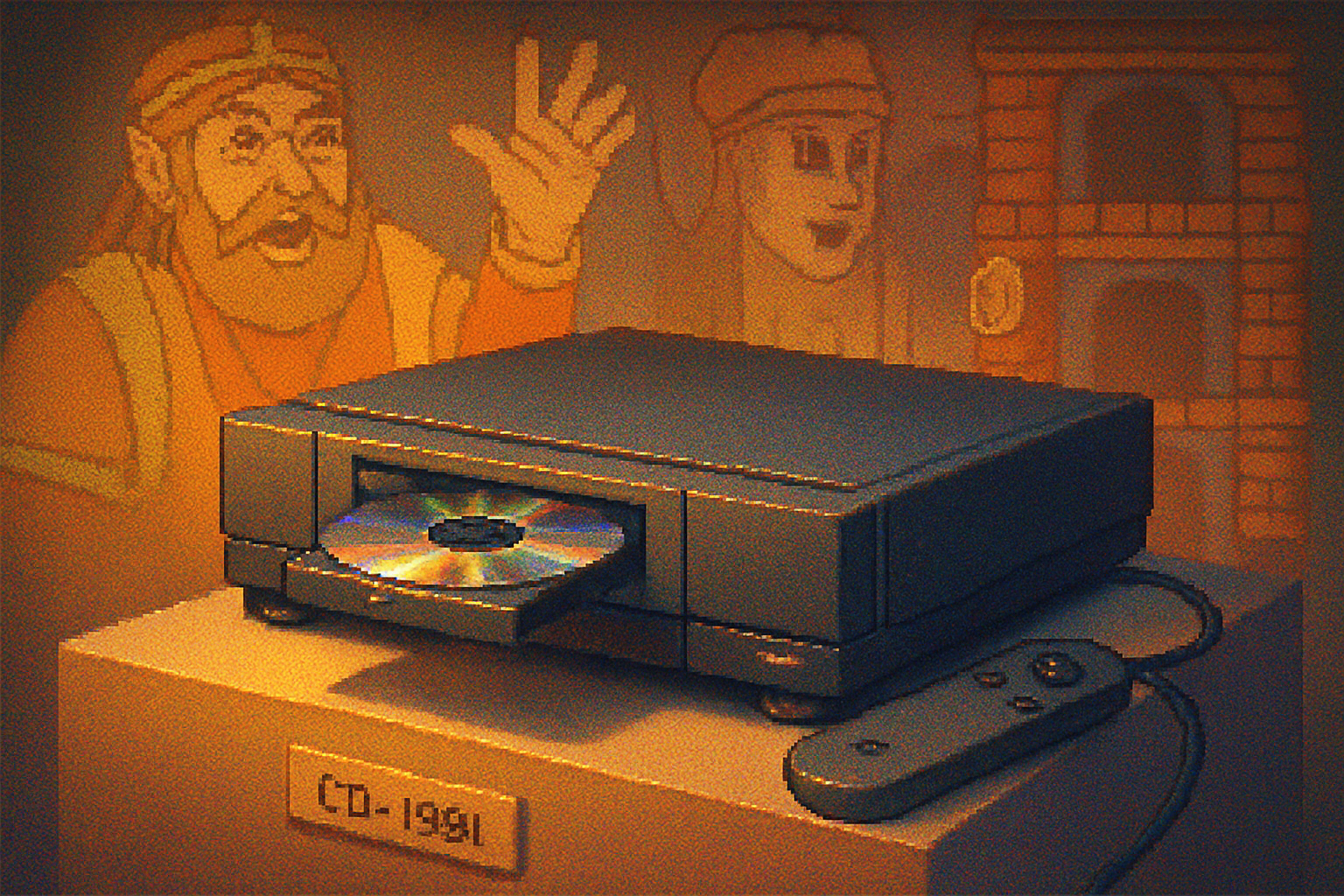

The Rise and Fall of the Philips CD-i: Why Emulators Might Be the Future

A deep retrospective on the Philips CD-i: how an ambitious multimedia console became a cautionary tale, and how emulators are now the most realistic path to preserving and re-experiencing its controversial library.

A bizarre, ambitious experiment

In the early 1990s, Philips - a global electronics giant - tried to pivot the CD-ROM format into an all-in-one multimedia entertainment platform: the Compact Disc Interactive, better known by consumers as the Philips CD-i. Marketed not just as a games console but as a multimedia appliance (education, encyclopedias, interactive video, music and games), the CD-i promised to bring the future of interactive media into living rooms.

That future never quite arrived. The CD-i’s library is remembered more for infamy than impact: awkward licensed games, baffling FMV experiments, and a handful of interesting but under-supported titles. Yet in recent years, emulators and preservation projects have given the platform a second life - prompting renewed interest and raising bigger questions about the role of emulation in preserving gaming history.

How the CD-i came to be

Philips began developing CD-i as a way to extend the compact disc into richer interactive media. Unlike the consoles from Nintendo and Sega that were squarely focused on gaming, Philips pitched the CD-i as a cross between a set-top multimedia device and a home computer. The system used CD-ROMs as media and offered full-motion video playback and multimedia authoring tools for a variety of non-game applications.

For a thorough timeline and technical overview, see the Philips CD-i page on Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philips_CD-i

Hardware and the developer story (short)

The CD-i was built around the idea of being an open multimedia platform rather than a tightly curated gaming console. That meant:

- CD-ROM media with FMV and audio streaming capabilities.

- A system architecture and middleware focused on interactive ‘titles’ rather than sprite-based action games.

- A controller and UI designed for menus and educational software as much as for action gaming.

Those design choices made the CD-i compelling for some multimedia developers but unattractive to many traditional game studios who preferred either the low-level control of cartridge systems or the growing CD-based consoles with strong game-oriented toolchains.

The licensing deals that would haunt the system

One of the most notorious parts of the CD-i story is how Philips ended up with the rights to produce games starring Nintendo characters like Mario and Zelda. In short: Philips and Nintendo briefly partnered on a CD-ROM add-on for the Super Nintendo that fell through; Philips retained some licensing rights and later used them for its own titles. The result was a clutch of high-profile licensed releases - most famously Link: The Faces of Evil, Zelda: The Wand of Gamelon, and Hotel Mario - that were widely panned for their gameplay and production values.

For context on the Zelda CD-i notoriety and how it shaped the console’s reputation, see Kotaku’s piece: https://kotaku.com/the-legend-of-zelda-on-the-cd-i-are-so-bad-theyre-legend-5824825

Why the CD-i failed (the short list)

Several factors combined to doom the CD-i as a mainstream gaming platform:

- Poor market positioning - It tried to be everything - a computer, a CD player, an educational device and a game console - and ended up being none of them convincingly.

- Weak first-party gaming lineup - Philips had few blockbuster titles to drive adoption, and many of the games it released were middling.

- High price and confusing SKUs - Different CD-i models were priced variably and marketed inconsistently across regions.

- Technical and development friction - Game studios found the platform unfamiliar and difficult compared with cartridges or other CD consoles, so third-party support was limited.

- Public perception - The odd licensing releases and some embarrassingly poor titles made the CD-i an easy target for critics and late-night jokes, which hurt sales further.

The result was a platform that never achieved a strong market foothold and slowly faded as the 1990s progressed.

A strange legacy: memes, cult love and the ‘so-bad-it’s-good’ factor

The CD-i’s most persistent legacy is cultural rather than commercial. The off-brand Zelda cutscenes, the earnest but clumsy FMV experiments, and peculiar licensed products produced an unusual mix of nostalgia, mockery and genuine fascination. Clips and remixes from CD-i games live on across the internet and introduced the system to generations who never saw one in a retail aisle.

That notoriety has created a small but active community of collectors and fans who rescue, document, and celebrate the oddities of the format.

Emulation: resurrections, restorations and the preservation imperative

As original hardware becomes rarer, emulation has stepped in to help collectors, researchers and curious players access legacy software. Emulators recreate system behavior in software, allowing CD-ROM images and dumped firmware to run on modern PCs and devices. For projects like the CD-i, emulation is attractive for several reasons:

- Accessibility - Emulation lets people experience titles without needing dusty, failing hardware.

- Preservation - Discs degrade, physical players break. Digital preservation via accurate dumps and emulation helps keep titles playable.

- Research and restoration - Emulators make it feasible to debug, patch, translate or remaster games that otherwise would be locked away.

Long-standing emulator projects (and broader multi-system emulators such as MAME) are important reference points for preservation work: https://www.mamedev.org/

Technical and legal hurdles unique to the CD-i

Emulating the CD-i is not as simple as copying a single ROM file. The platform depends on multiple pieces that must be dumped and emulated accurately:

- Firmware and system BIOS that were often proprietary.

- Unique CD-i file systems and multimedia codecs used for FMV and audio.

- Hardware idiosyncrasies and timing quirks that some software depended on.

- Copy-protection and licensing complications for titles using third-party encoders.

Legally, emulation itself is generally legal, but distributing BIOS firmware, commercial CD images, or copyrighted proprietary assets without permission is not. Many preservationists follow the stance that archiving must be done ethically: dump from media you own, preserve historically significant content, and, when possible, work with copyright holders. When rights-holders disappear or won’t cooperate, preservationists argue that emulation is the only realistic way to prevent cultural loss.

The Internet Archive and other digital preservation bodies have taken steps to make historical software available to researchers and the public, though the legal picture remains complex: https://archive.org

Emulators in action: what revival looks like

For the CD-i, emulation work has yielded several real outcomes:

- Restored video and audio assets from damaged discs, allowing historians to reconstruct games.

- Rehosted and playable versions of oddball titles for scholars and curious players.

- Fan-led fixes, translations, and mods that make obscure titles more accessible and better understood.

Even the most ridiculed CD-i titles benefit from this approach: studying them helps us understand commercial licensing missteps, early FMV design, and the cultural forces that shaped 1990s interactive media.

What this means for retro gaming

The CD-i story illustrates a wider truth about retro gaming: many platforms we now value were near-forgotten in their time, and many of those libraries risk irretrievable loss without active preservation. Emulators make this work possible and democratically available, but they also force us to confront thorny ethical and legal questions:

- Who owns digital cultural artifacts decades after their commercial life ends?

- When a console fails commercially, is there an obligation for curators or the public to preserve its work?

- How should preservationists balance respect for copyright with the need to prevent cultural erasure?

For the CD-i specifically, emulation is arguably the most practicable option for preserving and studying its output. Original hardware will remain valuable to collectors and as a tactile reference, but emulators provide the platform for broad, long-term access.

Closing thoughts

The Philips CD-i was neither the triumphant multimedia revolution Philips envisioned nor a complete failure without merit. It sits somewhere in between - an ambitious experiment that went wrong in ways that are instructive and, in some cases, strangely charming. Emulation doesn’t erase the CD-i’s failings, but it does let us examine them more closely, preserve their artifacts for posterity, and give a new audience access to a curious chapter of gaming history.

If there’s a lesson here for retro enthusiasts, historians and preservationists alike, it’s this: systems that seemed irrelevant or embarrassing in their era can become vital historical documents. Emulators give us the tools to read those documents - but if we want those documents to survive, we must do the messy work of dumping, documenting, and defending their existence before the physical media and the people who remember them are gone.