· retrogaming · 7 min read

The Evolution of Graphics: How TurboGrafx-16 Paved the Way for Modern Gaming

The TurboGrafx-16 (PC Engine) was a small machine with a big attitude. This article traces how its hardware and media innovations - from compact HuCards to CD-ROM audio - nudged game graphics and design toward the cinematic, colorful, and texture-rich experiences we expect today.

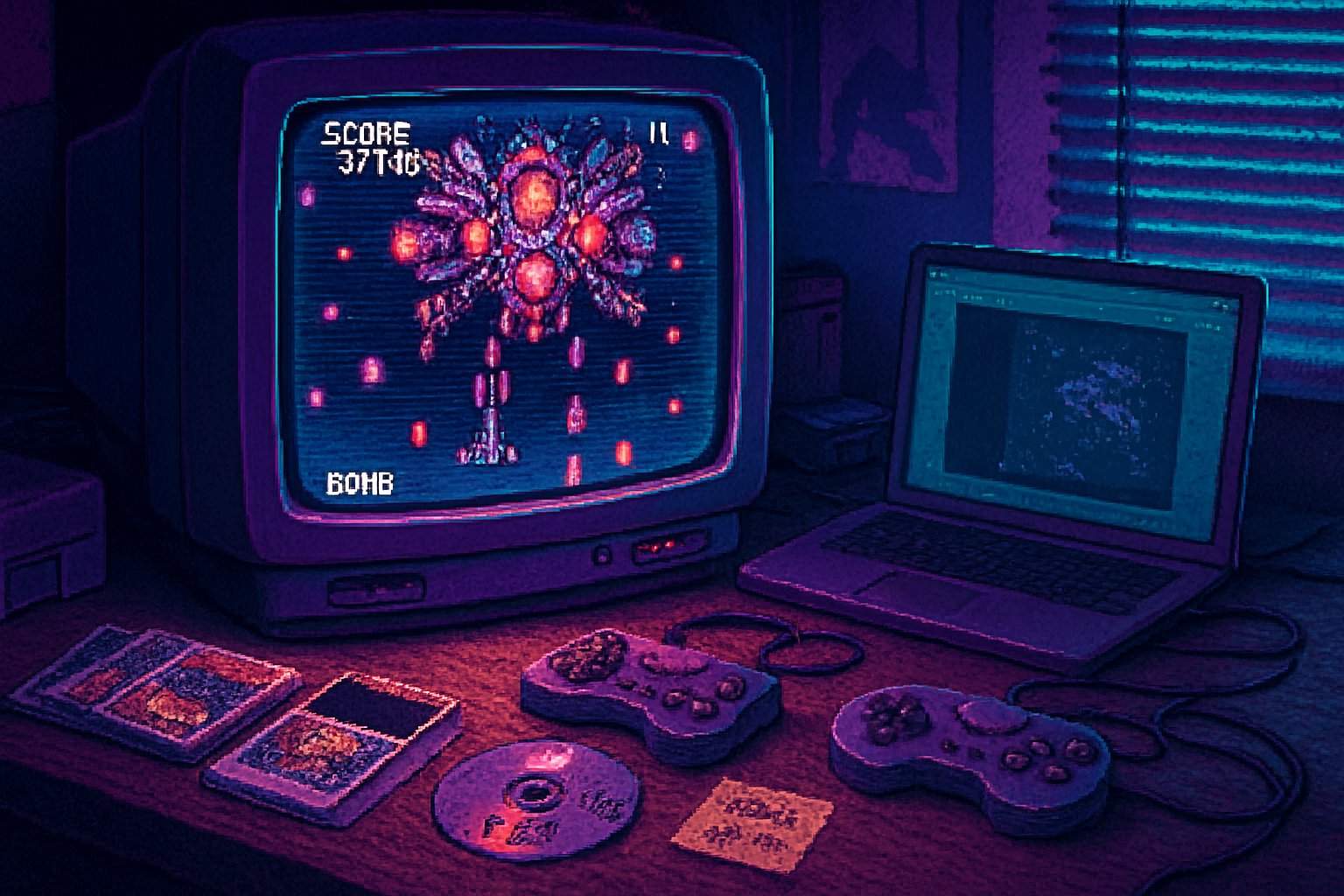

A kid in 1989 slides a shiny, credit-card–thin cartridge into a tiny console and, for a moment, believes the machine just swallowed the future. That little card was a HuCard, and the console was NEC and Hudson’s PC Engine - known in the West as the TurboGrafx-16. The image is telling: a compact object delivering visuals that often outwitted bulkier, supposedly ‘more powerful’ competitors.

The wild claim that needed to be made

The TurboGrafx-16 didn’t win the international console wars. It did something less glamorous and far more important: it forced developers and hardware makers to think differently about how graphics were produced, stored, and experienced. The result was not only prettier sprites; it was a set of practical techniques that nudged game design toward the cinematic and the richly textured - the bread and butter of modern gaming.

Why the PC Engine looked - and felt - ahead

Calling the PC Engine a trendsetter is easier if you understand its three practical revolutions:

- Compact, fast media that changed distribution psychology (the HuCard).

- A video pipeline that favored tile/sprite flexibility and arcade-like ports.

- The CD-ROM add-on that married music, voice, and storage to graphics.

Each of these elevated design possibilities in different ways. Below, we unpack them with concrete examples and the technical choices that mattered.

1) HuCard: small physical size, big design implications

The PC Engine’s HuCard (not a floppy, not a cartridge - a credit-card-sized ROM) looked like it belonged in a wallet. But its impact was cultural and logistical:

- It made distribution sleeker and cheaper, which encouraged experimentation in game length and content variety. See more about the HuCard format here.

- The format reinforced the arcade-to-home ethos. Developers used tight, efficient code and highly optimized graphics to squeeze arcade-quality animations into slim packages.

This enforced economy produced disciplined design. When storage or CPU cycles are scarce, you learn to prioritize: sharper sprites, smarter parallax, richer animation loops. Those priorities became a heritage that influenced handhelds and later cartridge-based systems.

2) A graphics pipeline built for sprites, tiles, and speed

Technically: the PC Engine used a video subsystem and an 8-bit CPU that together handled tile maps and sprites in a way that favored arcade-style presentations. Marketing called it a “16-bit” system in some regions, which was technically debatable (the CPU was HuC6280, an 8-bit processor with features that punched above its weight) - but the core point is the same: the machine produced visuals that looked like they belonged in arcades. See the hardware overview here and the CPU reference here.

What mattered to developers was not the nominal bit-width but this:

- A tile/sprite architecture that allowed dense backgrounds with repeatable tiles and independently animated foreground sprites.

- Hardware horizontal and vertical scrolling that produced smooth parallax effects.

- Efficient sprite handling that let many onscreen objects animate fluidly.

Those capabilities made arcade ports - titles that mimicked or matched arcade fidelity - more feasible on a home console. The PC Engine’s roster includes many arcade ports that retained strong visual identity, such as R-Type, Darius, and various shoot‑‘em‑ups.

3) TurboGrafx-CD: the long tail of storage and audio

The CD-ROM add-on is where the PC Engine’s influence becomes unmistakably modern.

- Suddenly, developers had tens to hundreds of times more storage than HuCards allowed. That meant longer stages, higher-quality music, and recorded voice acting.

- Music stopped being cheap bleeps and became orchestral arrangements or CD-quality tracks. Games like the CD releases of Ys leveraged Red Book audio to produce a soundtrack that felt cinematic. You can read about the TurboGrafx-CD here and about titles like Ys I & II that used CD audio.

The CD era began a shift in expectations: graphics alone no longer created immersion - the combination of art, animation, sound, and length did. That is a direct throughline to modern practices where art, music, and narrative are developed hand-in-hand.

How these choices influenced design patterns

Here are the concrete ways TurboGrafx-16 shaped game design that later generations amplified:

Prioritizing sprite detail over raw polygon counts. The PC Engine showed how much character and readability sprites could have if you focused on palette, shape, and animation. This legacy persisted in handhelds and certain indie aesthetics.

Treating audio as a partner to graphics. Early CD-based releases made voice and layered music a design tool for atmosphere and narrative pacing. Later consoles adopted this as standard.

Lean, optimized content design. The HuCard’s constraints trained a generation of developers to optimize assets and code - an ethic that made ports and indie experimentation more feasible.

Arcade parity as a selling point. The PC Engine’s ability to approximate arcade visuals proved a design and marketing model - give the home player an arcade-like spectacle, and you’ll sell hardware.

Concrete examples - games that showcased the lessons

Bonk’s Adventure - a defining mascot platformer that used large, expressive sprites and colorful backgrounds (the series showcased what large, well-animated sprites could do in the 16-bit context). See Bonk here.

Ys I & II (CD) - an early, effective use of CD audio to transform a soundtrack into a driving, cinematic force that elevated the game’s visuals and pacing. See Ys here.

Castlevania - Rondo of Blood - a technical and artistic showcase for what the CD add-on could do with audio and longer presentation values; its staging inspired later action-platformers. See Rondo of Blood

Shoot-‘em-ups and arcade ports (R-Type, Darius) - these games demonstrated tight sprite handling and smooth scrolling that rivaled arcade hardware of the day.

What the TurboGrafx-16 didn’t do - and why that matters

It’s tempting to mythologize any early success. But the PC Engine lacked the global market reach of Nintendo or Sega, which limited the spread of its direct influence. Still, accurate influence rarely needs to sweep the world; it only needs to point design directions that others pick up. In this case, three of those directions were taken and extended:

- CD-ROM as mainstream add-on (later seen with Sega CD and, more decisively, with PlayStation-era optical media).

- Emphasis on audio as narrative/atmosphere tool.

- Tile-and-sprite efficiency lessons that carried into portable and indie development.

A short, contrarian technical morality tale

If hardware is money, then the PC Engine was a credit card: small, efficient, and uncanny in what it could purchase. Bigger machines won battles for headlines. The PC Engine won a subtler war: it taught designers how to wring cinematic presence out of tight pipelines and modest silicon.

In that sense, the console acted like an annoying, brilliant schoolmaster. It punished inefficiency and rewarded craft. The games that learned the lesson look, sound, and feel closer to what we expect from modern titles than many bulkier contemporaries.

Legacy - what modern developers owe the PC Engine

You can draw direct lines from PC Engine practices to modern game production:

- CD-quality music and voice acting as staples of narrative pacing.

- Focused sprite art and animation techniques that survive in pixel-art indie games.

- Disciplined asset optimization taught by small-media formats, echoed in modern constraints (mobile, indie budgets, download sizes).

Most importantly, it taught a generation that perceived power is often a product of design, not just silicon. That’s a lesson both humbling and eternally useful.

Final thought

The TurboGrafx-16 didn’t build the world we live in today single-handedly. But it did point at a future where storage, audio, and clever graphics pipelines matter as much as raw compute. For anyone who cares about how games look, move, and feel, that’s a legacy worth remembering.

References

- PC Engine / TurboGrafx-16 - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/PC_Engine

- HuCard - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HuCard

- TurboGrafx-CD - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TurboGrafx-CD

- HuC6280 CPU - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HuC6280

- Bonk series - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bonk_(series)

- Ys I & II - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ys_I_&_II

- Castlevania - Rondo of Blood -