· retrogaming · 6 min read

Controversial TurboGrafx-16 Titles: The Games That Pushed Boundaries

A look at the TurboGrafx-16 / PC Engine releases that raised eyebrows - from blood-slick horror to occult pinball to Japan-only adult CD-ROMs - and how those controversies helped shape attitudes toward violence, sexuality, and localization in games.

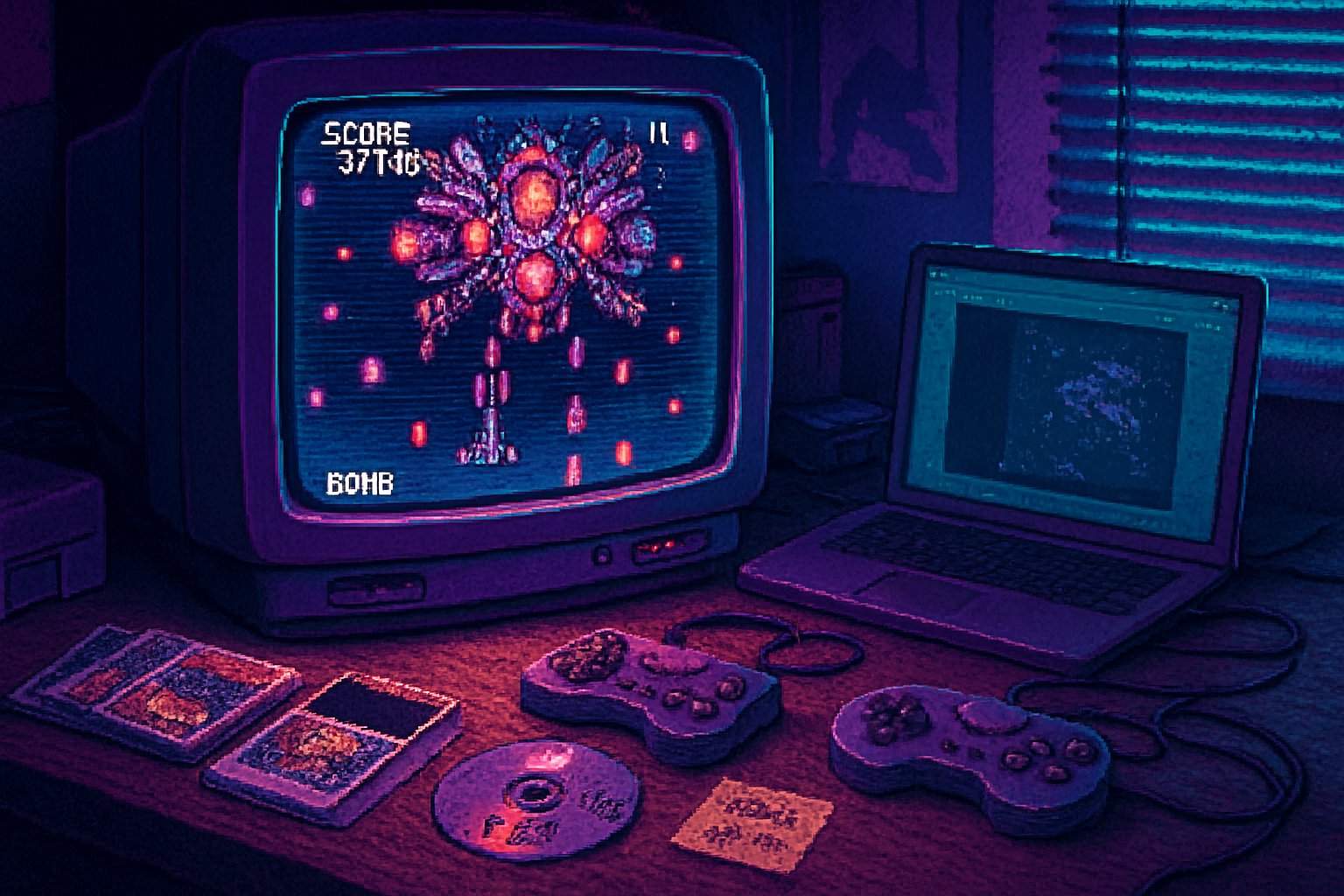

I remember a rental-store shelf from 1991: a dim fluorescent strip, a row of VHS boxes, and a single videogame case whose cover seemed to have been designed by a mad cartoonist with a taste for entrails. That was the moment the TurboGrafx-16 stopped being “another console” and became a small, scandalous window into how far games could go.

This is not nostalgic gushing. It’s an examination: which TurboGrafx-16 / PC Engine titles actually provoked outrage, why they did, and what - if anything - their controversies mean now.

The context: TurboGrafx-16 vs. PC Engine (and why it matters)

A quick clarification before we get sentimental: the TurboGrafx-16 is the western branding of NEC’s PC Engine. The machines were hardware cousins, but their libraries diverged. In Japan the PC Engine and especially its CD-ROM add-on hosted a large number of mature, experimental, and outright erotic titles that never saw western stores. Conversely, western TurboGrafx-16 marketing leaned family-friendly, and many of the risqué or graphic titles were either never localized or quietly altered.

Read that sentence twice. It explains most of the weirdness we’re talking about.

Sources: general background on the platform and its library are covered on the PC Engine page and related histories (PC Engine - Wikipedia).

The obvious: Splatterhouse - horror that refused to be cute

Why it raised eyebrows

Splatterhouse was not subtle. It was a straight, pulpy homage to 1970s/80s giallo and grindhouse horror - cracked skulls, chain-sawing baddies, and a protagonist who looks like he borrowed his faceplate from a low-budget slasher flick. The TurboGrafx-16/PC Engine port brought that visceral, gory arcade sensibility into living rooms.

What made it controversial then

- Graphic aesthetics - decapitations and grotesque enemy designs were rare in mainstream home consoles at the time.

- Atmosphere over restraint - Splatterhouse wore its gross-out cards on the table, not unlike a slasher movie trying to be a game.

Cultural footprint

Splatterhouse was part of a slow creep: video games could be horror in tone and content, not just in name. It pre-dates the ratings debates that dominated the ’90s but fed the public sense that games had escaped the sandbox.

Reference: Splatterhouse (video game) - Wikipedia.

Devil’s Crush - pinball with demonic art direction

Why it raised eyebrows

Devil’s Crush is a pinball game. It is also a shrine to occult, infernal, and very gothic iconography: skulls, altars, shrieking gargoyles and a soundtrack that sounds like it was recorded in a candlelit crypt. For a family-room console, that aesthetic felt transgressive.

What made it controversial then

- Visual religiosity - some retailers and consumers bristled at the overtly satanic imagery, even if the gameplay was essentially marble-flipper physics.

- Packaging and marketing dissonance - the box art and in-game visuals suggested a product aimed at older teens or adults, which clashed with the TG-16’s family-friendly persona.

Cultural footprint

Devil’s Crush is a reminder that controversy doesn’t need explicit sex or gore. Symbolism - religious or political - can make a game feel dangerous. That atmosphere helped broaden what game designers thought audiences would accept.

Reference: Devil’s Crush - Wikipedia.

The Japan-only darker side: CD-ROM eroge and the PC Engine’s adult library

Why it raised eyebrows

Thanks to the PC Engine CD-ROM format, developers could add voiced scenes, animated cutscenes, and adult imagery. Japan’s market included numerous erotic and mature visual novels / RPG hybrids - the so-called eroge - that pushed sexual content far beyond what western console audiences expected.

What made it controversial then

- Cultural mismatch - Titles that were acceptable in niche Japanese markets looked shocking to Western eyes when (rarely) glimpsed or when screenshots circulated.

- Platform perception - the PC Engine’s library of erotic titles made an odd contrast with the TurboGrafx-16’s western brand image.

Representative examples

- The Dragon Knight series and similar adult-oriented RPG/adventure games existed on Japanese PC and console platforms and showcased how the CD-ROM add-on could be used to produce highly explicit scenes.

Cultural footprint

These releases mattered because they exposed developers and consumers to the idea that consoles could host content aimed squarely at adults. That played into later conversations about ratings, retailer policies, and regional localization decisions.

Reference: discussion of the PC Engine’s adult titles and examples (PC Engine - Wikipedia; Dragon Knight (series) - Wikipedia).

Why did these controversies matter? (Spoiler: they helped make modern games tolerable)

- They expanded the notion of what videogames could be

Games stopped being cartoonish diversions and became media that could pursue tone - horror, erotic drama, anti-religious satire - with teeth.

- They forced industry decisions on localization and retail

Developers and publishers had to decide: alter the game, bury it in Japan, or fight to release it uncut. Those choices shaped the kinds of games western audiences saw.

- They created pressure for clearer content-labeling systems

The 1990s rating debates (and the eventual creation of the ESRB) are commonly linked to Mortal Kombat and Doom, but the groundwork included many earlier titles that showed content could shock. For the debate, every bloody sprite and every suggestive cutscene counted. See: Entertainment Software Rating Board - Wikipedia.

Reference: broader overview of controversies in games (Video game controversy - Wikipedia).

How these cases look today

- Splatterhouse - Viewed as a cult classic, campy and sincere. The shock is muted, but the design still feels brash.

- Devil’s Crush - Appreciated for its ambition - the occult aesthetic is now a selling point for collectors.

- PC Engine eroge - Still problematic for many; historically interesting for scholars studying censorship, localization, and changing norms surrounding sex in games.

What’s changed: context. Violence and sexual content are far more visible today. The controversies of the TurboGrafx/PC Engine era read now as early skirmishes in a much larger cultural war about who games are for.

Design lessons from the edge

- Tone is design. A single art-direction choice can shift a product from ‘toy’ to ‘text.’

- Platform branding matters. A console’s perceived identity can mute or amplify controversy.

- Localize or die. The choices publishers make about edits and markets shape cultural memory.

If you want to shock gamers in 2026, gore and occult imagery aren’t the only routes. Ambitious storytelling, uncomfortable perspectives, and formal experiments do the job - and they’ll be controversial in more interesting ways.

Final thought - controversy as pedigree

The TurboGrafx-16 and PC Engine didn’t win the console wars. But their boundary-pushing titles left a small, important legacy: they showed that consoles could host work meant for adults and that art-direction alone could ignite debate. In that sense, controversy isn’t just an awkward footnote. It’s pedigree - proof the medium was growing up.

If you find yourself nostalgic for those garish covers and lurid CD jackets, know this: the outrage they provoked helped create the ecosystem that allows a studio today to release a bloody, haunted indie or a frank, adult story - and have it taken seriously.