· retrotech · 6 min read

The Controversial Legacy of Early Photoshop: Empowering vs. Misleading Artists

Early Photoshop felt like magic: layers, selection tools and the clone stamp turned anyone with a scanner into a studio artist. That same toolkit also rewired our relationship to truth in images. This opinion piece examines how early Photoshop both liberated and misled artists, and why the debate about what counts as 'real' art still matters.

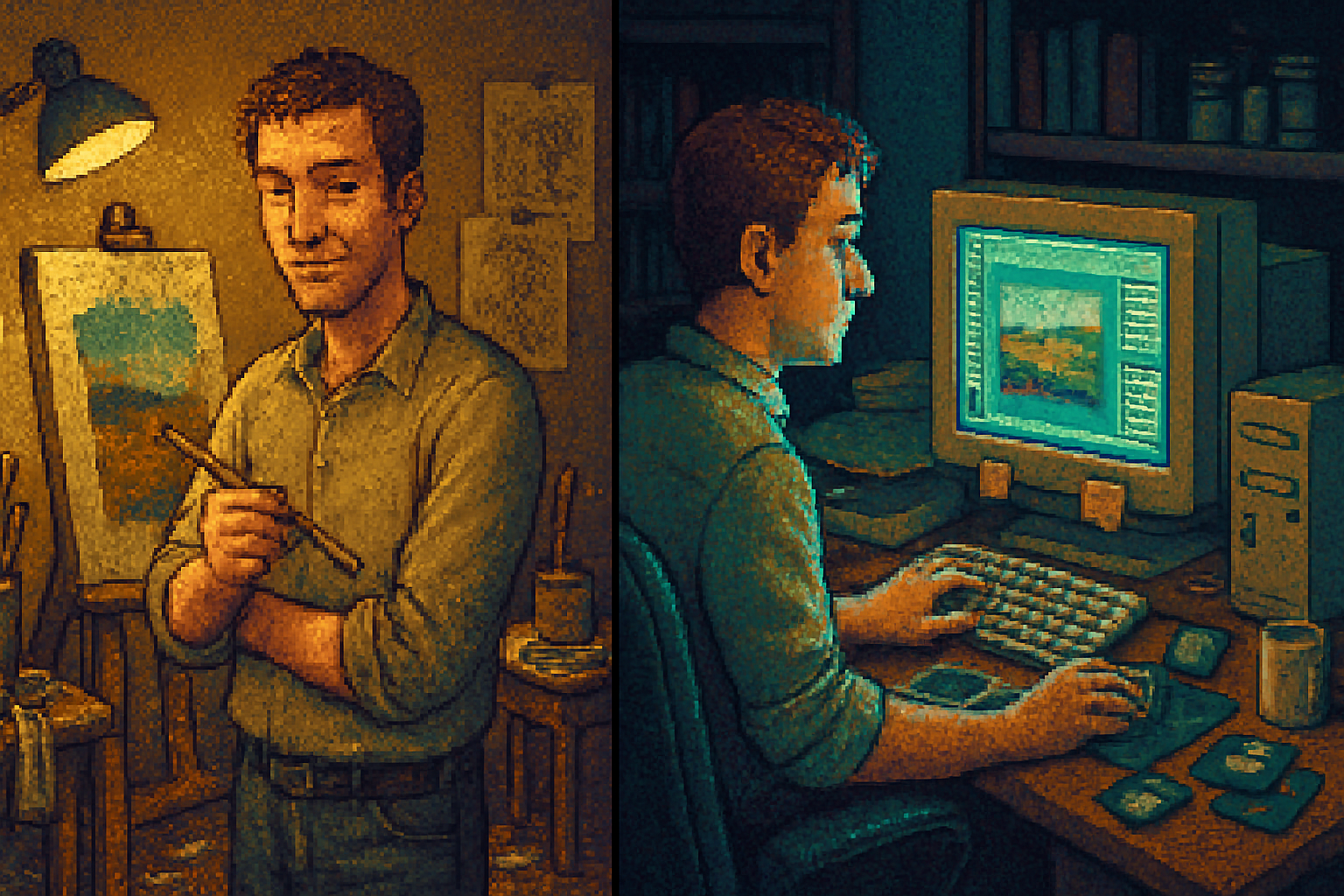

I remember the first time I watched someone use the clone stamp on a scanned photograph. It was mesmerising - a seamless patching of skin and sky that felt less like editing and more like conjuring. The person at the computer looked like a sculptor, except the clay was pixels and the chisel was a cursor.

That conjuring is the origin story of a controversy that has only grown louder. Early versions of Photoshop didn’t invent image manipulation. They democratized it. They put a 19th‑century darkroom’s power into the hands of anyone with a modem and a few dollars for software. The result was ecstatic, messy, brilliant - and ethically ambiguous.

A quick history note (so we know what we’re arguing about)

Photoshop arrived in 1990 and, over the next few releases, added features that rewired how people made images: layers (which appeared in Photoshop 3.0), selection tools, and retouching tools such as the clone stamp. These features lowered technical barriers and increased creative possibility almost overnight. For a concise timeline, see Adobe/Photoshop histories and the version history summary on Wikipedia.

The obvious upside: empowerment, speed, new aesthetics

Let’s be frank. Photoshop was liberating in ways that matter:

- Democratization - You no longer needed a full studio, an expensive camera or a long apprenticeship to compose complex images. A motivated teenager with patience could outwork a traditional studio apprentice.

- Iteration at scale - Layers and nondestructive workflows let artists experiment without mortgaging every early idea. Courage follows from being able to erase mistakes.

- New aesthetics - Photomontage, collage, and hybrid forms that blend painting, photography and graphic design flourished. Early digital painters - a lineage that runs through Craig Mullins and countless concept artists - used Photoshop to create work impossible with traditional tools alone.

- Cross-pollination - Photographers learned painterly techniques; illustrators adopted photographic realism. The entire visual ecosystem learned new tricks fast.

These are not small advantages. Photoshop accelerated skill acquisition and diversified who got to make visible work.

The shadow side: where empowerment becomes mendacity

But every tool has consequences. The same interface that enabled fine art also enabled mendacious retouching and persuasive deception.

- Journalistic ethics - Once subtle edits could erase or rearrange facts, the bedrock of photojournalism - that a photo indexes reality - was cracked. Discussions about manipulation and truth in images predate Photoshop, but the software made casual falsification trivial. See debates around photographic manipulation in journalism

- Advertising and body image - Airbrushed impossibilities migrated from high‑end magazines into mainstream expectations. The clone stamp and healing brush were deployed to make human bodies conform to an algorithm of desirability - and that algorithm became lethal for many people’s self‑image.

- The slippery slope to propaganda - If you accept small, undetected changes for aesthetic reasons, you lower the bar for politically motivated distortions. The history of image-based persuasion is old; Photoshop made it cheaper and faster.

This is not hyperbole. The ethical failures are not merely aesthetic; they affect memory, politics and social norms.

So: is ‘real’ art about technique, intent, or visible labor?

The controversy ultimately rests on a vocabulary problem. When people complain that Photoshop makes art “not real,” they usually mean one of three things:

- Technique authenticity - The work lacks visible manual trace - no brushstrokes, no camera grain, no smudges.

- Intentional honesty - The image claims to document reality but has been altered in ways that mislead.

- Labor valorization - Skilled handcraft is romantically prized; automation and shortcuts are dismissed as lesser craft.

Each claim is defensible. But each is also porous.

- Technique authenticity confuses medium with message. A photorealistic digital painting can require as much discipline and eye as an oil study. The absence of a palette knife doesn’t make a good idea bad.

- Intentional honesty is the clearest boundary - passing manipulated images as documentary is bad. But if a photographer or artist is transparent about technique, the conversation shifts from “fraud” to “aesthetic choice.” Transparency is the simple ethical lever.

- Labor valorization often hides class snobbery. If software compresses drudgery - background replacement, color correction - should we worship the part of practice that was never interesting in the first place?

A few concrete fault lines

- Advertising vs. fine art - Advertisers lie. That’s their business model. When advertising tactics bleed into documentary or fine art without disclosure, friction and outrage are predictable and justified.

- Competition and the creative economy - For commercial photographers, Photoshop reduced turnaround times and increased client expectations. The result: higher productivity demands and, sometimes, lower pay for labor that clients expect to be instantaneous.

- Education and craft - Design programs adapted quickly; fine art curricula lagged. The result was a generation of artists whose default toolbox included digital techniques, which changed both process and pedagogy.

Rules of thumb for artists and viewers

Here are pragmatic guidelines that respect both the liberating power of tools and the need for ethical clarity:

- Declare your intent. Is this a documentary image, a composite, a study? Label it.

- Respect domain expectations. Photojournalism and scientific imagery deserve stricter standards than conceptual art or advertising.

- Teach craft and thinking together. Tool fluency without conceptual rigor produces clever but hollow work.

- Make provenance legible. File histories, captions, and process shots are small nudges that rebuild trust.

The long tail: Photoshop’s legacy is now everyone’s problem

The early debates about Photoshop were a prelude to larger anxieties about authenticity in the digital age. Deepfakes, generative AI, and real‑time manipulation are intellectually continuous with the clone‑stamp era: they extend the same capability curves, but faster and often with less visible labor.

If Photoshop taught us anything, it’s that tools change culture. They reconfigure trust before institutions catch up. The moral conversation around images has to focus less on banning tools and more on designing norms and incentives. We need legal and cultural guardrails - and better visual literacy in the public.

Final provocation

Photoshop did two things at once. It gave artists superpowers and it made deception cheap. Those facts are both true. The hard work is deciding which truth matters in which context.

Is the answer stricter policing, more transparency, or a cultural acceptance that “real” art is not bound to visible labor? I don’t think there is a single answer. But I do think we can stop pretending that a tool alone can make an image honest or dishonest. Honesty is a practice.

What do you think? Where should we draw the line between creativity and realism? Share a story of a time Photoshop changed your idea of what an image could be.