· retrotech · 6 min read

Angelfire: The Forgotten Pillar of Internet Communities

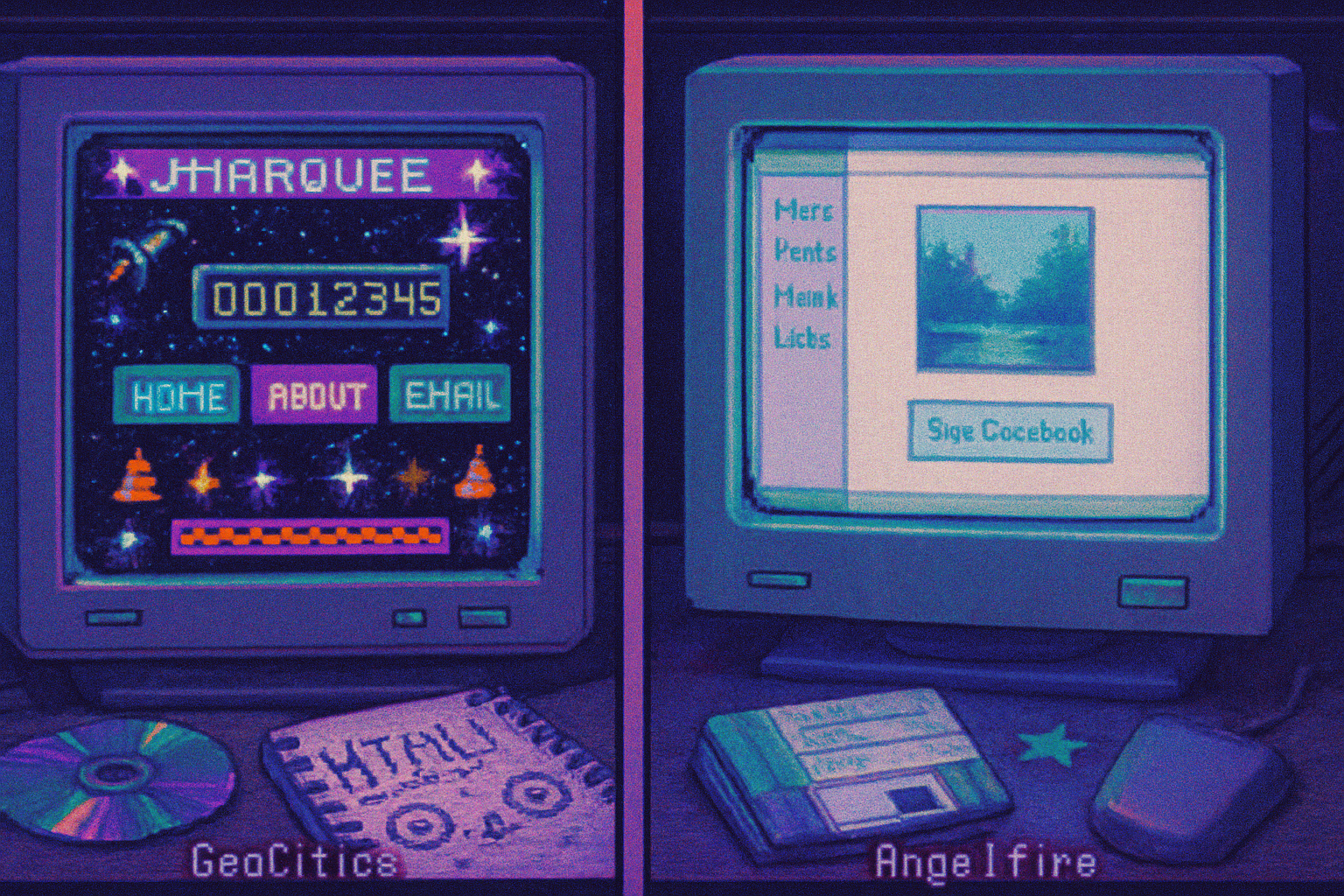

Before timelines, likes, and algorithmic feeds, Angelfire pages-glitter GIFs, guestbooks, and hand-coded fan shrines-were where friendships were made and communities learned how to be social online. This piece traces how those small, home-made corners anticipated the social networks we use today and why their lessons still matter.

I still remember the sensation: a tiny animated star zipped across the top of a stranger’s Angelfire page, a guestbook entry below reading “added you! :)” and a list of links that led me through three fandoms, a poetry zine, and someone’s painstakingly hand-coded Johnny Depp shrine. It felt like trespassing into someone’s attic and being handed a cup of tea.

That attic, of course, had a hit counter and an autoplaying midi. It was Angelfire.

The scene before the feed

Angelfire arrived toward the late 1990s as one of a handful of free web-hosting services that turned the wild, static web into a patchwork of personal stages. Users could create full pages with raw HTML, drop in a guestbook widget, paste glittering GIFs, and trust that the page would live - imperfectly, lovingly - on the public internet for anyone with a dial-up connection and a taste for Comic Sans.

If you think social media began with a single app, try thinking of it as the slow accretion of countless personal pages, each one a micro-community. Angelfire sites were not platforms in the modern sense; they were canvases. But those canvases started doing something that platforms would later monetize: they became places for people to find one another, exchange signals of friendship, and coordinate belonging.

(For a concise overview of Angelfire in the context of late‑90s hosting services, see the Angelfire entry on Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Angelfire.)

Guestbooks, hit counters, and the earliest social mechanics

Modern social networks stitch together a handful of simple mechanics - profiles, comments, follower lists, public content - and Angelfire pages were where many of those mechanics first matured in public view.

- Guestbooks = comments/walls - Visitors left timestamps, shout-outs, and crude conversational threads in guestbooks. Those entries were explicit, archived, and public - the web’s primitive comment section.

- Personal pages = profiles - A page with photos, favorite lyrics, and an “about me” section was a pre-Facebook profile. It said who you were and signaled who you wanted to meet.

- Link pages = social graphs - Link exchanges and “friends” pages built networks. People curated roll lists and linkbacks as deliberate social signals.

- Hit counters = vanity metrics - Users watched counters tick like early analytics - not for ad dollars, but for reassurance that someone, somewhere, had seen them.

- Message boards and scripts = groups - Many Angelfire sites plugged in forum scripts or linked to Perl/CGI message boards. These were structured spaces where ongoing conversation and identity-building happened.

These features weren’t invented on a whiteboard. They evolved from practice. The social idea was simple: make a small corner of the internet and invite people in.

How communities actually formed (not just ‘liked’)

The social life on Angelfire and similar hosts wasn’t driven by algorithms. It was driven by ritual and craft:

- Fandom micro-economies - Fans built companion sites for bands, TV shows, and actors. They exchanged fan art, torrent-naïve music discussions, and episode analyses. These sites were often the earliest organized fandom hubs.

- Roleplay and creative collaboration - Text-based roleplaying communities grew on user pages, using linked profiles and threaded guestbook exchanges to sustain long-running stories.

- Local and school networks - High-schoolers used Angelfire pages as personal portfolios and class hubs - a public but intimate space where friendships were announced and tested.

- Link rings and shout-outs - Reciprocal linking created a navigable social web. If you were linked on someone’s “friends” page, you’d get linked back, and a mini-network would emerge.

These practices produced durable human outcomes: friendships, offline meetups, long-term collaborations. They weren’t ephemeral because an algorithm decided so; they were maintained by people who cared about the small things - a custom banner, an image gallery, a weekly update.

Why Angelfire matters to the history of social media

We tell the story of the internet as a linear march toward platforms. That’s convenient, but it obscures a crucial truth: many of the primitives of social software were worked out on these DIY pages, in public.

- Agency and customization - Angelfire empowered users to control layout, copy, and linking in ways that modern platforms often prevent. That freedom produced identity experiments that felt authentic because they were crafted, not templated.

- Slow, archival sociality - Guestbooks and pages built implicit archives. Conversations aged visibly, becoming artifacts rather than vanishing into feeds.

- Local moderation and norms - Community standards emerged from user culture. Without centralized moderation, groups learned to enforce norms or self-segregate - messy, but instructive.

Clay Shirky’s early essays about the politics of groups and the affordances of social software help explain why these small, self-governed communities mattered: groups form around shared practice and tools that reduce coordination costs [https://www.shirky.com/writings/group_politics.html].

The darker corners (yes, there were trolls)

Nostalgia can sanitize. The Angelfire era had its downsides:

- Gatekeeping and cliques - Small communities sometimes hardened into exclusionary cliques.

- Harassment and permanence - Public guestbooks could be sites of bullying with no easy recourse.

- Fragility - When hosts changed policies or died, entire communities vanished - a problem of centralized dependency.

Still, these harms were often local and tangible. When something went wrong, you usually knew who to talk to - the site owner - and communities found ad-hoc responses.

Preservation, nostalgia, and the archaeological impulse

When GeoCities was shut down and later memorialized, people realized how ephemeral this creative work was. Projects like the Wayback Machine tried to rescue fragments of those pages (https://web.archive.org/), and digital historians have used saved Angelfire pages to study early online life.

Nostalgia for Angelfire isn’t just about glitter GIFs. It’s about the memory of agency: the pleasure of building your own corner of the web and watching a community gather there.

Design lessons for modern platforms

If you design communities today, Angelfire has a few uncomfortable lessons:

- Let people craft identity. Heavy templating lowers friction but also flattens expression.

- Preserve conversation. Visibility and archiving make communities legible and accountable.

- Encourage small groups. Platform-wide virality is intoxicating; small, sustained groups create depth.

- Make data portable. Users should be able to export their work; when hosts die, communities shouldn’t vanish.

In short: combine the craft and ownership of old personal pages with the usability and safety of modern systems.

Conclusion - what Angelfire still whispers to us

Angelfire pages looked messy because they were human. They weren’t optimized for attention economies or ad targeting; they were optimized for people who wanted to say, “This is mine.” That impulse - to create, to invite, to archive - is the quiet ancestor of everything we call social media today.

We remember platforms as monoliths. But the social web was built by attics: tiny, idiosyncratic rooms where people practiced being social online. The lesson is simple and stubborn: give people space to build, and they’ll build a world you didn’t expect.

References

- Angelfire - Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Angelfire

- GeoCities - Wikipedia (context on hosting-era culture): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/GeoCities

- The Wayback Machine (Internet Archive): https://web.archive.org/

- Clay Shirky - “Group Politics and Social Software”: https://www.shirky.com/writings/group_politics.html