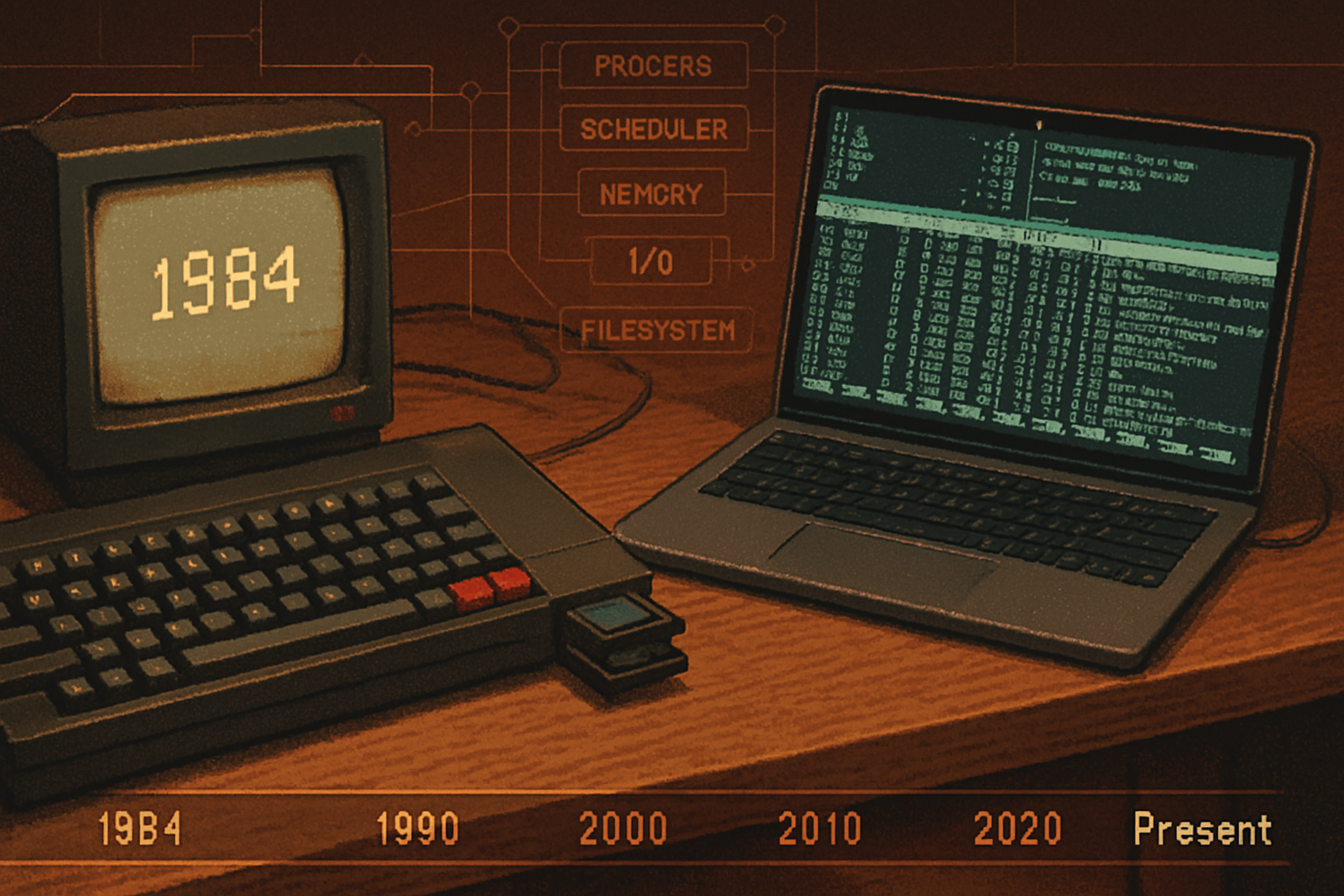

· retrotech · 6 min read

Why the Sinclair QL Deserves a Modern Revival

The Sinclair QL, with its counterintuitive genius - cheap, small, multitasking, and modular - offers a design philosophy that could inspire a new generation of devices combining clarity, thrift and hacker-friendly expandability.

It begins with a cartridge that smells faintly of hot plastic.

I remember seeing one slide into a small silver box in 1984 - a curious little ‘microdrive’ click, a whir, and a machine that promised business computing for the price of an expensive calculator. It failed in many practical ways: dodgy firmware, a storage medium that would eat data like an impatient shark, and a launch so rushed it felt like a prototype shoved out the door. But beneath the chaos there was a coherent idea: make useful computing cheap, compact, and extensible. That idea still matters.

The case for the QL - more than nostalgia

Most people remember the Sinclair QL (Quick and Low-cost) as an ambitious misfire. Fair enough. But if you strip away the failures - the flaky microdrive, the rushed ROM, the marketing missteps - what’s left is an unusually modern philosophy for a mid‑1980s machine:

- Lightweight, integrated hardware that expected the user to extend it, not to buy a tower of peripherals.

- A focus on compactness and affordability without pretending to be disposable fashion.

- An early embrace of multitasking and an opinionated OS aimed at professionals.

- A hacker-first culture - built to be opened, tinkerable, and extensible.

Those design priorities read today like a checklist for sustainable, human-scale computing.

What the QL got right (and why those things matter now)

1) Minimalism that encourages creativity

The QL didn’t try to be everything to everyone. It shipped with built-in programming tools (SuperBASIC) and a few productivity packages, and expected developers and users to build on that foundation. That’s a healthy constraint. In an age where devices try to hide complexity behind endless apps and cloud lock-in, a clearly opinionated, local-first platform is refreshing.

Analogy: the QL is like a small kitchen with a few excellent knives rather than a mansion with rooms full of single-use appliances.

2) Room for expansion

Sinclair’s approach was modular. The QL’s ports and expansion bus invited third parties (and home tinkerers) to add capabilities. Modern IoT and edge devices would benefit from that same spirit: default simplicity with periphery freedom.

3) Multitasking in a tiny package

Long before multitasking was a checkbox on every spec sheet, the QL shipped with a pre-emptive multitasking OS (at least in intent). That shows a design that anticipated real work, not just games and hobbyist scripts. A revived QL philosophy might reward modern devices that do a few things concurrently and elegantly, rather than dozens poorly.

4) Cheapness as design, not a marketing tag

Cheapness for the QL wasn’t about shaving features to maximize margin; it was about rethinking which features were essential. This is a lesson for hardware designers who confuse “feature creep” with “value.” Affordable, purposeful devices can be more democratic than all‑bells luxury boxes.

How a modern QL revival could look

The idea isn’t to build a museum piece with a failing magnetic tape loop. It’s to translate the QL ethos into sensible modern components and open policies.

- Hardware - A compact aluminium shell, a tactile keyboard, modest modern CPU (ARM or RISC‑V), a small SSD or hot‑swap microSD cartridge bay that echoes the microdrive but with real reliability.

- Software - An open, small-footprint OS inspired by QL principles - deterministic, local-first, lightweight multitasking, with a built-in scripting language and a curated set of productivity apps.

- Expandability - Exposed GPIOs, an expansion bus for HAT-style modules (Wi‑Fi, LoRa, DACs), and a friendly serial/USB console for tinkerers.

- Persistence - Instead of Microdrives, use removable encrypted flash ‘cartridges’ or USB-C pocket SSDs that click into a slot and are hot-swappable.

- Community tooling - A modern equivalent of the QL’s Active Third‑Party scene - SDKs, emulators, and package repos that lower the bar for making useful add-ons.

Concrete product ideas

- The QL Pocket - A clamshell device with a mechanical keyboard, e-paper or low‑power color display, focused productivity apps, and a modular bay for storage or radios. Think: purposeful laptop for writers, students, and sysadmins.

- The QL Hub - A tiny, headless edge server for homes and small businesses - local-first sync, backup, and automation, with a physical cartridge for quick system restore or app bundles.

- Modular dev kit - A no‑nonsense board with exposed headers, a small OS image preinstalled, and community‑approved modules so makers don’t reinvent the wheel every time.

Why indie designers and retro fans will care

Two converging cultural currents make a QL-style device plausible now:

- Retro computing has become a design value. People don’t just want the look of the old machines - they want the constraints and the creativity those constraints permit.

- A backlash against cloud monoculture. Users increasingly want devices that keep control, are repairable, and don’t vanish if a company shutters an online service.

A QL revival channels both: the romance of vintage tactile design combined with modern openness and durability.

The challenges (so we’re not dreaming recklessly)

- Brand and IP - The Sinclair name carries weight, but rights are fragmented. Any revival would do well to be explicit about licensing.

- Nostalgia vs. practicality - If a product leans too hard on nostalgia, it becomes a novelty. It must solve real problems.

- Market fit - The mainstream market prizes convenience and ecosystems. A revival should target makers, educators, privacy-minded users, and retro enthusiasts first.

A pragmatic route to revival (step-by-step)

- Build an open reference design (hardware and OS) and release it under permissive licenses.

- Ship a small batch ‘prototyping kit’ with modern cartridges and dev docs to seed communities.

- Encourage emulation and modern clones of the QL’s ideas (not a pixel-perfect museum), and support porting of beloved QL apps.

- Use crowdfunding to validate demand and fund a small run, with stretch goals for certified third‑party modules.

Lessons from history: what the Sinclair story teaches designers

The QL’s failure wasn’t an ideological one; it was operational. Haste and unreliable storage sunken a bright, economical concept. But the lesson is constructive: design cannot be separated from delivery. If you build a device that endorses tinkering, ship it with robust basics - sane storage, clean firmware, thoughtful defaults.

Think of the QL as an ancient apple tree: it produced sour fruit when harvested too early, but there’s good stock in the roots.

Final argument: why designers should steal from Sinclair

Design thinking is cyclical. The current hardware zeitgeist - where repairability, local-first software, and expressive minimalism are prized - is the QL’s native habitat. Reviving the Sinclair QL’s design philosophy would not be an exercise in kitsch. It would be a return to values many modern devices have forgotten: clarity, humility, extendability, and the belief that a piece of hardware can encourage exploration instead of enclosure.

If you’re a designer, a maker, or someone who remembers that computing can be a craft as much as a service, steal this: build cheap things that invite improvement, not lock them away. The QL’s mistakes are instructive. Its instincts are underrated.

References