· retrotech · 6 min read

The Sinclair QL: A Controversial Figure in Computing History

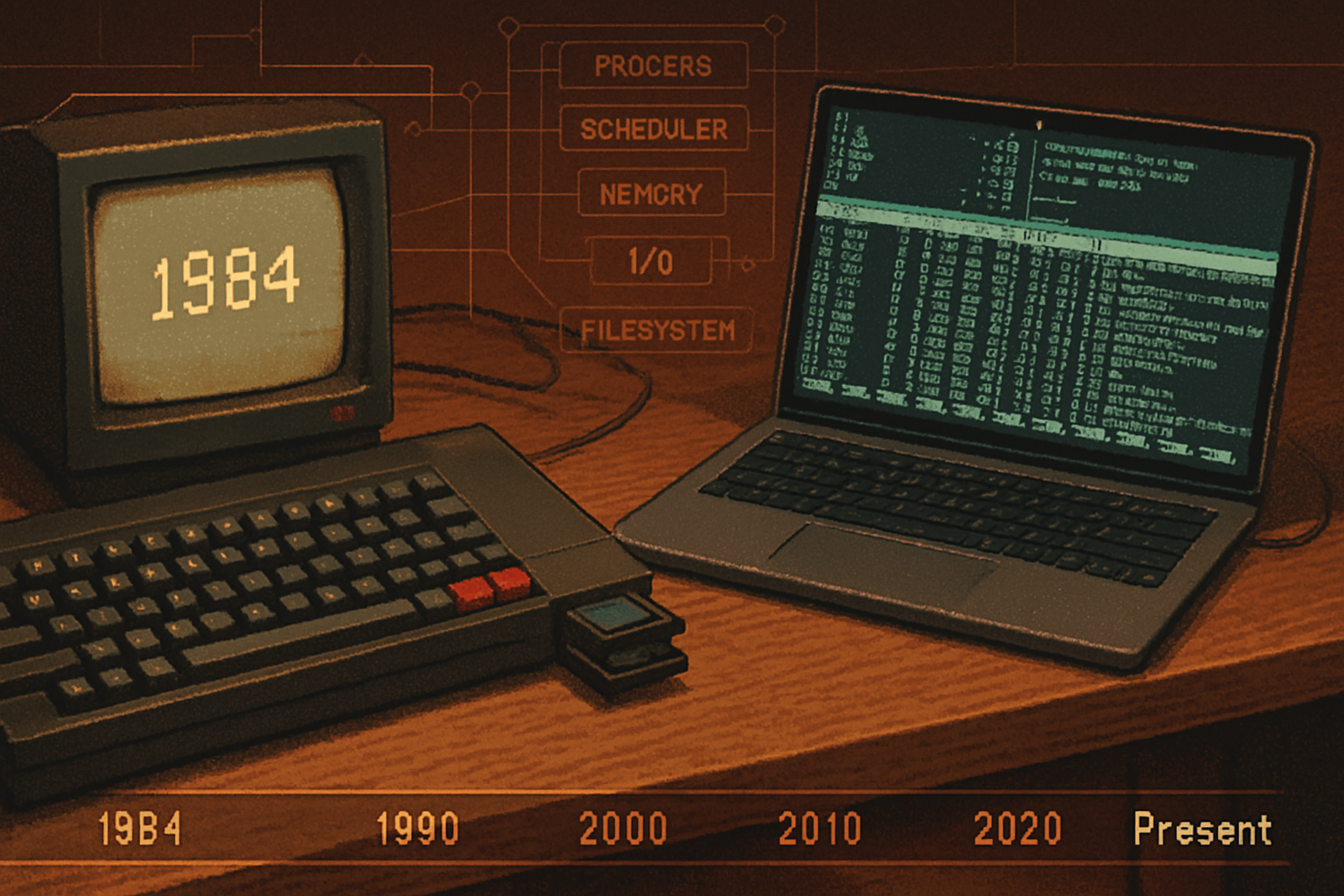

The Sinclair QL promised to leapfrog business microcomputing in 1984 - but rushed launch, flaky microdrives, and buggy ROMs made it a cautionary tale. The QL changed what consumers demanded from personal computers: stability, real storage, and a working OS out of the box.

An engineer in a suit once announced a miracle in a glass-and-chrome showroom and handed you a miracle that leaked. That was the QL: brimful of cleverness, marketed as a business workhorse - and equipped with a tape-loop storage system that behaved like a temperamental cuckoo clock.

The Sinclair QL (Quantum Leap) arrived in early 1984 with a crisp sales pitch: more power than your home micro, affordable for small business, and a new operating system for serious work. What arrived in many users’ hands was…ambition outpacing polish. The controversy that followed wasn’t just about one machine; it helped reframe what buyers would come to expect from personal computers.

What the QL promised - and why people believed it

Sinclair had earned enormous consumer trust with low-cost, high-impact machines such as the ZX Spectrum. That success made the QL feel inevitable: a step up from bedroom hobbyism to small-office professionalism. The spec sheet was compelling on paper:

- Motorola 68008 CPU (an economical cousin of the 68000) running at 7.5 MHz

- 128 KB RAM built-in, expandable

- Built-in networking/serial I/O and networking ambitions (QLAN)

- Two built-in Microdrive tape-loop cartridges for mass storage

- A ROM-based operating system (QDOS) and the interactive SuperBASIC

The promise: a relatively inexpensive “business” micro that could run spreadsheets, word processors and connect to printers - without the enterprise price tag.

The core criticisms at launch

When launch-day users tried to turn promise into work, several flaws were impossible to ignore. These issues fall into two clusters: performance architecture and reliability/quality.

1) Performance - more theory than practice

On paper the QL’s 68008 should have felt fast compared with 8-bit micros. In practice the real-world experience was more complicated:

- The 68008 uses the 68000 instruction set but with an 8-bit external data bus. That reduced the throughput advantage and introduced significant bottlenecks compared with full 16/32-bit designs.

- The system’s memory and I/O architecture, plus the overhead of the ROM-based environment, meant tasks - particularly disk (microdrive) I/O and graphics - were slower than users expected.

- SuperBASIC and bundled ROM software were useful but not optimized for heavy business workflows; CPU and I/O bottlenecks were revealed under real workloads.

The result: the QL felt clever but not convincingly faster than many existing alternatives - a bitter pill for buyers promised a “quantum leap.”

2) Reliability and quality - the fatal wound

This is where the QL’s reputation suffered the most.

- Microdrives - Sinclair’s low-cost cassette-like tape-loop cartridges were inventive but fragile and error-prone. They offered higher capacity than cassettes at the time but were notoriously unreliable, slow, and prone to data loss. For a machine pitched at small businesses, fragile storage was unforgivable. See

- ROM bugs and firmware issues - Early QDOS/SuperBASIC ROMs had bugs. Patching ROMs was awkward; band-aid solutions and rejected promises eroded consumer trust.

- Launch readiness - Evidence suggests Sinclair pushed machines out quickly to meet market windows and publicity timetables. The result was a product that felt shipped prematurely - hardware and software teetering at the edge of acceptability.

- Poor third-party software availability for business use at launch further weakened the QL’s value proposition.

Together these problems read like a lesson in prioritizing launch over longevity: a seductive product that, for many, did not survive first contact with real workloads.

Why the controversies mattered beyond Sinclair

The QL’s failure wasn’t just a PR embarrassment for one company. It shifted consumer and industry expectations in durable ways.

Consumers learned to expect three things

Real, reliable storage out of the box. Microdrives taught buyers to distrust exotic, proprietary storage when inexpensive disk drives (floppy disks) proved far more dependable. The market increasingly favored machines that shipped with or supported reliable disk systems.

A working OS and usable software at launch. A computer that can’t run useful applications immediately is a financial risk. The QL made buyers insist that new models be usable and stable, not merely showpieces for clever hardware.

Product maturity over novelty. The QL’s mix of cleverness and fragility made buyers more skeptical of headline-grabbing features that prioritized novelty (and lower cost) over robustness.

Manufacturers took note

By 1985–86, alternatives that emphasized maturity gained traction. The Commodore Amiga and the Atari ST arrived with more solid storage options (floppy drives), stronger multimedia and real-time capabilities, and ecosystems that felt ready for work and play. They benefited from buyer wariness of half-baked launches.

- Commodore and Atari emphasized shipping systems with working OSes and better storage options.

- Software houses became more cautious about platform bets - a platform’s stability and user base mattered more than headline specs.

The press and the market grew more skeptical

Reviewers and business buyers began to treat press previews and showroom demos with more cynicism. The honeymoon era of euphoric coverage for every spec sheet faded; reviewers demanded end-to-end validation (hardware, OS, storage, software) rather than vanity metrics.

The QL’s quieter afterlife: community, hacks, and legacy

The QL didn’t die outright. A dedicated community patched ROMs, created disk interfaces, and built third-party hardware and software. Those efforts salvaged useful life from the machine and demonstrated the resilience of hobbyist ecosystems. But by then the mainstream had moved on.

In retrospect, the QL’s legacy is mixed but instructive:

- It showed how innovation without operational durability can blow up a product’s promise.

- It accelerated a market preference for real storage, polished OSes, and mature ecosystems.

- It reinforced that timing a launch for marketing reasons - rather than shipping a robust product - is a strategic gamble that often fails.

Lessons that still matter (and sting)

The QL reads like a cautionary fable for modern product teams. Strip away the 1980s hardware and replace it with cloud services or consumer hardware, and the moral is unchanged:

- Novelty can’t substitute for reliability. Consumers will forgive a lot, but not repeated data loss.

- Shipping early to impress investors or press is fine - as long as customers don’t get the short end of the stick.

- Ecosystems matter. If developers and third parties can’t build reliable applications for your platform, your hardware becomes a very expensive sculpture.

Sinclair gambled on ingenuity and cost-leadership. The gamble produced a beautiful, brittle machine: admired by tinkerers, loathed by businesses whose ledgers went missing.

Final thought - why the QL still matters

The QL didn’t kill Sinclair, and it didn’t kill computing’s forward march. But it helped harden consumer expectations. After the QL, buyers became less willing to believe brilliant demos and glossy brochures; they wanted the product that actually worked on Monday morning. That’s a small mercy for anyone who has ever lost a file to a clever but unreliable device.

References

- For technical and historical details see the Sinclair QL Wikipedia page.

- On the Microdrive’s design and issues, see Sinclair Microdrive.

- Broader context on Sinclair and his products: Clive Sinclair - Wikipedia.

- For contemporaneous market context and successors: ZX Spectrum, Amiga, Atari ST.