· retrotech · 7 min read

The Untold Secrets of NeXT's Unique Operating System: A Journey Through OPENSTEP

OPENSTEP wasn't just another OS - it was a manifesto: small, opinionated, and daringly object-oriented. This article walks through its architecture, design philosophies, key features, and the surprisingly direct line from NeXT's ideas to today’s macOS and iOS.

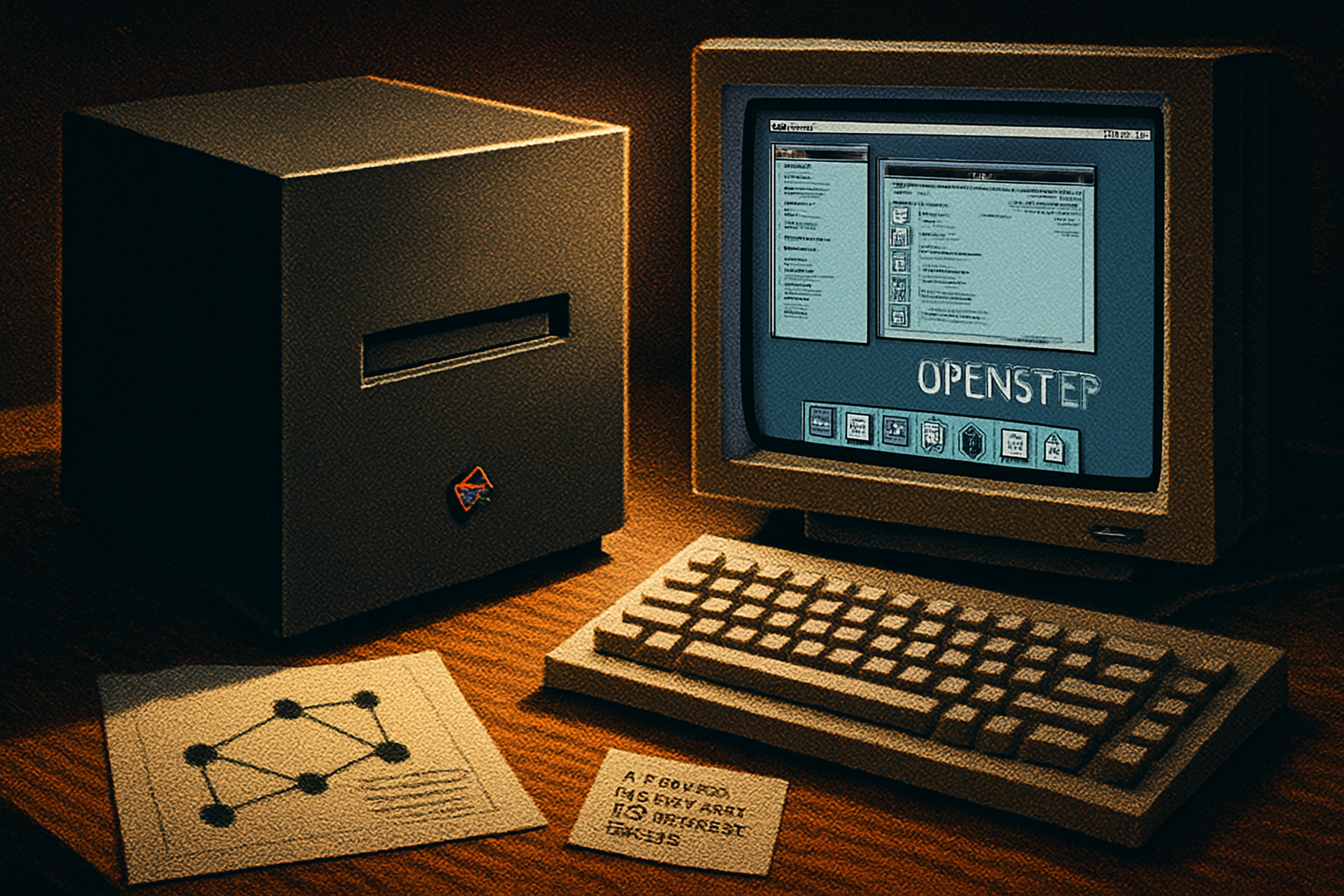

It began with a cube on a desk and a man who had decided to start from scratch. In 1990, while the rest of the industry was muttering about incremental improvements, NeXT shipped an operating environment that dared to be elegantly opinionated. That same machine hosted the first web server and browser - Tim Berners-Lee used a NeXTcube to birth the World Wide Web - and it quietly seeded ideas that now anchor modern operating systems [1].

Why OPENSTEP deserves a second, closer look

Most people know the headline: Apple bought NeXT in 1996 and, with it, the foundation of macOS and later iOS. But the real story is subtler. OPENSTEP wasn’t just code; it was a philosophy - a compact set of decisions about how software should be built, framed around objects, dynamic runtime behavior, and developer tools that treated composition as a craft.

If you’re an engineer who has cursed at a storyboard merge conflict, used Cocoa APIs, or benefited from the Objective-C runtime’s introspection - congratulations. You have OPENSTEP to thank, and you probably didn’t notice.

What was OPENSTEP, exactly?

OPENSTEP was an API specification and software environment originally developed by NeXT that exposed a consistent, object-oriented framework for building applications. Technically it was the evolution of the NeXTSTEP environment, refined and partially decoupled from NeXT hardware so it could be ported to other kernels and platforms [2].

At a high level, OPENSTEP combined:

- A small, well-chosen set of frameworks (Foundation and AppKit) that exposed high-level, reusable abstractions.

- A dynamic, message-based runtime provided by Objective-C, which made objects first-class citizens at runtime.

- A graphics system based on Display PostScript for crisp, resolution-independent rendering.

- A Unix/BSD compatibility layer and the Mach kernel underpinnings for modern process and IPC semantics.

Each of these pieces is unremarkable in isolation. Put together, they make a system that feels unified, readable, and - crucially - kinder to developers.

Architecture deep dive (the boring, glorious plumbing)

1) Kernel and system layer: Mach + BSD

OPENSTEP typically ran on a Mach microkernel with a BSD-derived userland. Mach provided message-based IPC, task/thread abstractions, and memory management primitives. BSD supplied the familiar Unix tools and network stacks. This hybrid gave developers POSIX compatibility while enabling the advanced process isolation and IPC that later macOS would keep [3].

Why it mattered: Mach’s message passing and ports turned out to be a clean substrate for higher-level services. The separation also made it possible to port OPENSTEP across hardware - an early exercise in OS modularity.

2) Objective-C runtime: dynamism as a feature

Objective-C wasn’t just a language; it was a runtime philosophy. Method calls are runtime message sends. Classes and categories can be inspected and manipulated at runtime. That dynamism made features like live object inspection, hot-swapping UI elements, and lightweight plugins practical.

A tiny taste:

// Objective-C messaging: dynamic, tiny, expressive

NSString *s = [[NSString alloc] initWithFormat:@"Hello, %@", name];

[s release];This dynamism fostered developer tools that felt alive rather than static.

3) Foundation and AppKit: APIs as taste

OPENSTEP’s APIs were ruthlessly opinionated. Foundation handled strings, collections, file I/O, and basic object behavior. AppKit provided higher-level UI elements and patterns such as event handling, responders, and views.

NeXT formalized Model-View-Controller (MVC) at the application framework level. MVC wasn’t an optional design pattern here; the frameworks nudged you toward it. That nudge codified a separation of concerns that still shapes how we design interactive apps.

4) Display PostScript: typography and fidelity

Instead of an ad-hoc raster pipeline, NeXT used Display PostScript. Pages and windows were vector-based and resolution-independent. That gave text a typographic clarity and page-like precision rare on screens in 1990 [4].

It was expensive computationally. It was brilliant.

5) Mach-O, dynamic loading, and process separation

NeXT introduced Mach-O as its binary format. Dynamic loading of object code (plug-ins, bundles) felt natural thanks to the runtime: drop a bundle in place, link it, and the system could discover and use it. This model foreshadowed modern plugin ecosystems and app extension models.

Design philosophies that still sting with truth

- Objects over accidental complexity. OPENSTEP treated code as a network of collaborating objects, not piles of procedures bolted together.

- Developer tools matter more than marketing. Interface Builder and Project Builder made UI assembly visual and testable. They reduced cognitive load and increased iteration speed.

- API as taste-maker. Instead of exposing everything, the frameworks offered curated, opinionated building blocks.

- Dynamism > rigidity. Runtime introspection and messaging made small changes less costly and large systems more malleable.

- UX is first-person. NeXT cared about typography, layout, and content as first-class citizens - not as afterthoughts.

These look like platitudes now. They weren’t then. They were borderline heresies.

Features that changed how people built software

- Interface Builder - Visual UI composition stored as nibs (archived object graphs). That idea is the ancestor of XIBs and storyboards in modern Xcode [5].

- Enterprise Objects Framework - an early object-relational mapping system that influenced Core Data’s approach to object persistence and model graphs [6].

- Workspace Manager - the NeXT desktop that managed documents, metadata, and launching in a way that favored clarity and discoverability.

- The dynamic runtime - categories, selectors, and message dispatch enabled patterns like delegation and lightweight aspect-like behaviors.

Each of these features looked indulgent or flaky to conservative OS designers. Each one stuck.

OPENSTEP’s direct line to modern systems

If you squint at macOS or iOS, you can see OPENSTEP’s fingerprints everywhere:

- Cocoa = the grandchild. Apple’s Cocoa frameworks are direct descendants of Foundation and AppKit. The naming changed; the DNA did not [7].

- Objective-C runtime → Swift’s interoperability. Even with Swift, Objective-C runtime features remain critical; bridging and dynamic behaviors still rely on the old machinery.

- MVC and Interface Builder survive in Xcode’s storyboards and nibs. They are more polished, but conceptually they are the same approach to UI composition.

- Display PostScript gave way to PDF-based Quartz, but the idea of a device-independent, vector-preserving rendering architecture remains central to macOS graphics.

- Mach kernel and Mach-O remain core parts of Darwin, the open source base of macOS and iOS. The separation of concerns Mach introduced is still part of Apple’s OS architecture [3].

In short: OPENSTEP is the ancestor you didn’t invite to Thanksgiving, but who quietly paid off your mortgage.

Concrete examples (history that changes your perspective)

- The World Wide Web was first delivered on a NeXTcube. Tim Berners-Lee wrote his original web server and the first browser/editor on NeXT hardware, leveraging the machine’s text and graphics capabilities to prototype hypertext elegantly [1].

- When Apple acquired NeXT, it wasn’t just buying a company; it was buying a development model, a runtime, and a set of tools that codified the idea that an OS should elevate creation, not just execution.

What modern OS designers can learn from OPENSTEP

- Pick fewer, better primitives. A smaller set of well-designed APIs reduces accidental complexity.

- Treat developers as first-class users. Fast iteration beats micro-optimizations for developer onboarding.

- Embrace runtime dynamism where it aids flexibility - but pair it with strong conventions and tooling.

- Invest in typography and layout. Presentation is not ornament; it’s comprehension.

Those lessons are cheap to state and expensive to adopt. NeXT paid the cost in product cycles and hardware bets. We have reaped the benefit.

A brief caveat on nostalgia

It’s easy to mythologize: “NeXT was perfect.” It wasn’t. Display PostScript was heavy. Objective-C’s manual memory management prior to ARC induced a generation of retain/release sorrow. Performance and hardware constraints mattered. But the ambition - to make software composition humane and durable - is what stuck.

Final: why OPENSTEP still matters

OPENSTEP teaches a simple, stubborn lesson: operating systems are not merely engines; they are frameworks of thought. They encode a worldview about how programs should be written, how people should interact with computers, and how complexity should be contained.

When you drag a control into Interface Builder, when a view controller responds to a selector, when a developer reaches for Cocoa instead of reinventing the wheel - that’s OPENSTEP. It’s quiet. It is not flashy. But it is everywhere.

References

- NeXTSTEP / OPENSTEP overview: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/OPENSTEP [2]

- NeXT and NeXTSTEP history: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/NeXTSTEP [2]

- Mach kernel and Darwin lineage: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mach_(kernel) [3]

- Display PostScript: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Display_PostScript [4]

- Interface Builder history: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interface_Builder [5]

- Enterprise Objects Framework: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enterprise_Objects_Framework [6]

- Cocoa API lineage: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cocoa_(API) [7]

- Tim Berners-Lee and the World Wide Web origin: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tim_Berners-Lee#World_Wide_Web [1]