· retrotech · 7 min read

The TI-99/4A vs. Contemporary Alternatives: A Comparative Analysis

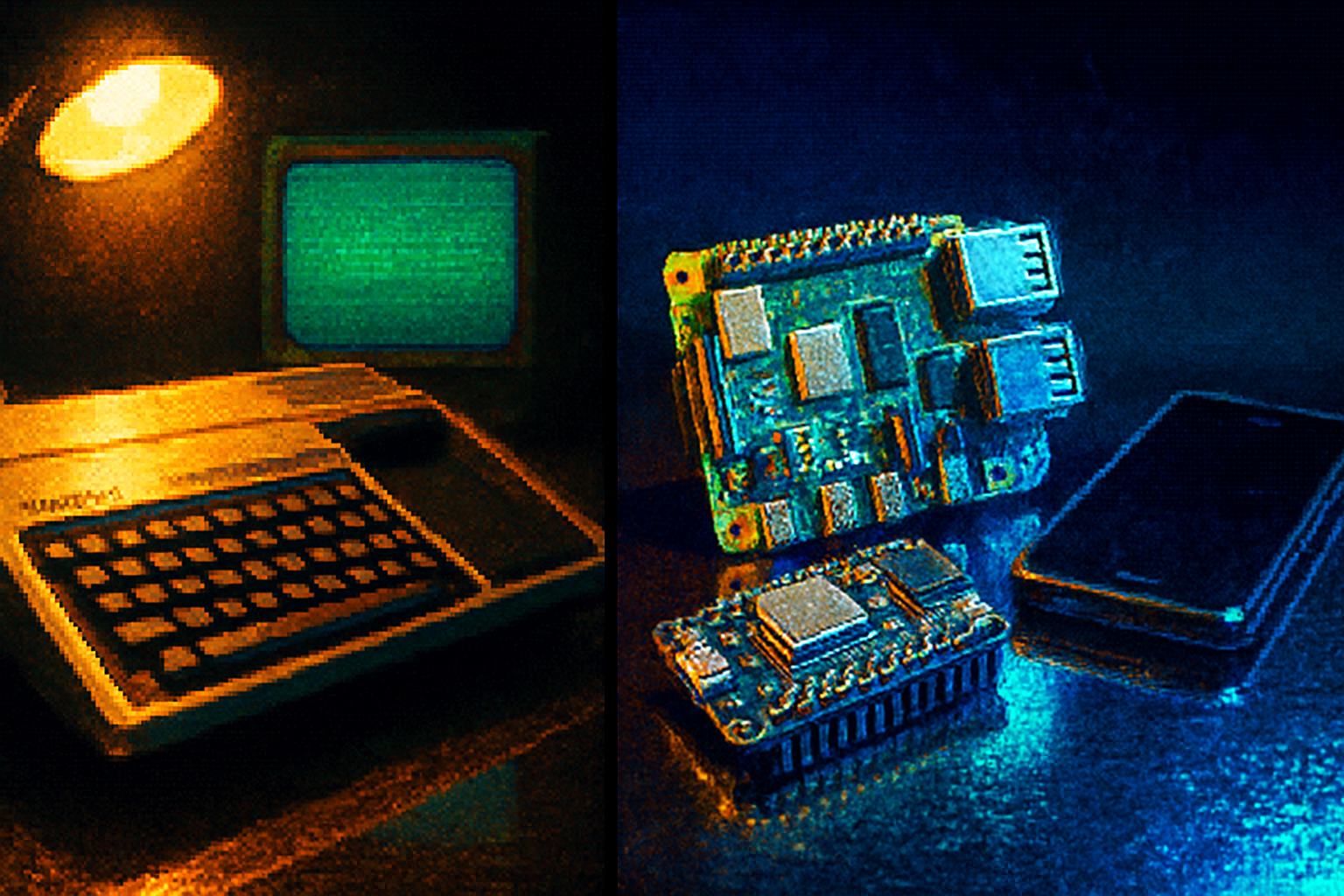

A contrarian look at the TI-99/4A: raw specs, architectural quirks, and why - despite being laughably underpowered by modern numbers - it still teaches us something useful about computing and human experience.

A boy in the early 1980s plugs a cartridge into a beige box with a piano-key keyboard, types a line of BASIC, and waits. The life-changing moment isn’t the code - it’s the blunt, tactile certainty of the machine doing exactly what it was told. Two decades later, that certainty is banished into firmware, software stacks and opaque drivers. The TI-99/4A, in all its clunky glory, is a useful touchstone for asking a modern question: when we measure computing power, what are we actually valuing?

This article picks apart the TI-99/4A’s memory, processing, and user experience, then lines it up against contemporary alternatives - microcontrollers, single-board computers, and smartphones - to show how the metrics we idolize can miss the point.

Quick technical portrait (so we can argue with numbers)

- CPU - Texas Instruments TMS9900, a 16-bit CPU clocked at ~3 MHz. It was a genuine 16-bit design at a time when 8-bit chips were dominant, but architecture matters as much as width.

- RAM - the system shipped with a tiny amount of CPU-accessible workspace - famously 256 bytes of scratchpad RAM - while the video chip (TMS9918A) had dedicated VRAM (about 16 KB) and much of the system’s routines lived in GROM/ROM. This split memory map is the root of much of the 4A’s performance oddities.

- Storage/IO - ROM cartridges and GROMs held software; disk and cassette were optional add-ons. Expansion modules (32 KB RAM card, speech modules, etc.) could change the experience.

With that nailed down, let’s compare.

Memory: bytes, architecture, and the illusion of capacity

Numbers first - then nuance.

- TI-99/4A - ~256 bytes of CPU workspace, ~16 KB VRAM, ROM/GROM for firmware and cartridges. Expansions could add tens of kilobytes.

- Modern microcontroller (RP2040 / Raspberry Pi Pico) - dual-core ARM Cortex-M0+ at 133 MHz, 264 KB SRAM, and typically several megabytes of QSPI flash for programs/data.

- ESP32 - dual-core Tensilica LX6 up to 240 MHz, ~520 KB internal SRAM plus external flash; commonly used with 4–16 MB flash.

- Raspberry Pi 4 (consumer single-board computer) - 1–8 GB RAM and full OS stacks.

If you judge solely by raw capacity, the TI loses before it starts. It is a match against a modern dog with a fire truck strapped to its back. But raw bytes miss two essential ideas:

- Architectural bottlenecks matter more than headline RAM. The TI’s CPU couldn’t access VRAM directly; the video chip was a separate coprocessor with its own memory. A 16-bit CPU hamstrung by indirect access to its program and data stores is slower in practice than a “narrower” chip with sane memory mapping.

- Purpose-built limited memory can shape usability in productive ways. Confining a learner to 256 bytes of workspace forces economy of thought. It’s an uncomfortable teacher; it makes you plan.

So: modern devices provide more memory, with far fewer architectural landmines. They also remove the constraints that, paradoxically, taught cleverness.

Processing power: clock speed, instruction set, and the hero that isn’t

Again, raw clock numbers lie.

- TI-99/4A TMS9900 - 16-bit instructions, ~3 MHz. A sophisticated design for its era, but often bottlenecked by slow ROM/GROM and the memory architecture.

- Microcontrollers - 100–240 MHz class (RP2040, ESP32), single- or dual-core, modern pipelines and predictable interrupt systems.

- SBCs and phones - multi-core ARM cores running at GHz speeds with out-of-order execution, large caches, and MMUs.

Why the TI’s 16-bit chip didn’t translate to perceived speed:

- Bandwidth - The TMS9900’s performance depended on the memory system. When much of the system’s code lived in GROM (slow, serial-access ROM), the CPU spent cycles waiting for data.

- Co-processing - Graphics and sound in the TI were handled by separate chips. That’s not a disadvantage per se - it’s modern heterogeneous computing - but the glue between elements was inefficient.

- Instruction throughput and modern microarchitectural features (pipelines, caches) that multiply effective performance simply didn’t exist.

Compare that to an ESP32: a 240 MHz dual-core MCU can run interpreted languages, manage Wi‑Fi, and host tiny web servers without breaking a sweat. A Raspberry Pi 4 is orders of magnitude beyond the TI; it is in a different universe.

But remember: clock speed isn’t the whole truth. The TI’s simplicity made timing deterministic - a blessing for debugging and teaching. Modern systems trade determinism for layers of abstraction.

User experience: the human side of computation

Here the TI-99/4A holds surprising advantages - not because it’s better, but because it’s different in ways that matter.

- Instant identity - The machine is a single-purpose object with a clear set of interactions: switch on, type, run. No OS updates, no background patches, no connect-to-cloud. There’s an honesty to that. The machine’s behavior is legible.

- Tangibility - The keyboard is a physical promise. Cartridges are physical commitments. You can touch the system and understand where programs live. Compare that with a phone: everything is a sealed ecosystem and, often, an app store contract.

- Determinism - For hobbyists writing tight loops or timing-based demos, the TI’s predictable timing (subject to its constraints) was easier to reason about than a modern multi-core, preemptively multitasked system with caches and power states.

- Friction as feature - Slow load times, memory limits - these are friction. Friction forces disciplines: modularity, memory economy, more thoughtful coding. Sometimes friction is how you learn to think.

Of course, for real productive tasks, modern UX wins by a mile:

- Rich displays, networking, storage, and modern input methods.

- Software ecosystems that let you stand on shoulders rather than digging tunnels.

So the trade-off is: clarity and constraint versus capability and convenience.

When the TI outshines modern boxes (and when it doesn’t)

Situations where the TI-99/4A still has charm or utility:

- Education and understanding - Teaching the discipline of resource-constrained programming.

- Retro gaming and demos - The social and aesthetic value is non-trivial.

- Deterministic hardware projects where the exact behavior of the system matters and you want predictable timing without layers of OS interference.

Situations where it fails spectacularly today:

- Networking, multimedia, modern development workflows, machine learning, or anything where RAM and CPU matter.

- Practical application development - you won’t run a modern web stack on a 4A (unless you consider porting small parts a fun and masochistic hobby).

Lessons for modern builders and hobbyists

- Constraints teach. The TI’s tiny workspace forced programmers to think. Modern platforms can emulate constraints (smaller microcontrollers, limited memories) for pedagogical value.

- Architecture beats raw specs. A broad bus, fast ROM, caches and sane memory maps make a huge difference. Modern systems show how far we’ve come in solving these problems - but also how opaque the results can be.

- UX matters as much as performance. People prefer systems that behave in predictable, legible ways. We surrender a lot of legibility for convenience.

- Nostalgia is not a technical argument. It’s a human one. When we say the TI is “better,” we usually mean the experience of using it taught or pleased us - not that it outperforms a Pi.

A final, mildly provocative verdict

The TI-99/4A is not secretly competitive against modern silicon. It would be absurd to say a 3 MHz TMS9900 with 256 bytes of workspace can outpace a 240 MHz microcontroller or a GHz-class ARM. The controversy would be comic if it weren’t instructive.

But if you measure “value” in terms other than throughput - readability, determinism, the cultivation of careful thinking - the TI remains a useful counterexample to our fetish for scale. It’s like comparing a pocket watch to a smartwatch: the latter does everything better and more reliably, but the former teaches you to read time with attention.

If you’re a maker who wants to learn, don’t start by buying the biggest, shiniest board. Try constraining yourself: hack a TI-99/4A heading back into service, program an 8-bit microcontroller, or deliberately limit RAM and see what you learn. The machines have changed; the habits of mind that matter haven’t.

References

- TI-99/4A - Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TI-99/4A

- TMS9900 - Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TMS9900

- TMS9918A (VDP) - Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TMS9918A

- RP2040 documentation - Raspberry Pi: https://www.raspberrypi.com/documentation/microcontrollers/

- ESP32 - Espressif Systems: https://www.espressif.com/en/products/socs/esp32

- Raspberry Pi 4 product page: https://www.raspberrypi.com/products/raspberry-pi-4-model-b/