· retrotech · 7 min read

The Rise and Fall of Netscape: Lessons for Today's Tech Startups

Netscape built the first modern browser business, sparked the dot-com rush, and then collapsed into irrelevance. Its story is a primer in product-market fit, distribution, platform risk, and the perils of fighting incumbents without a durable business model.

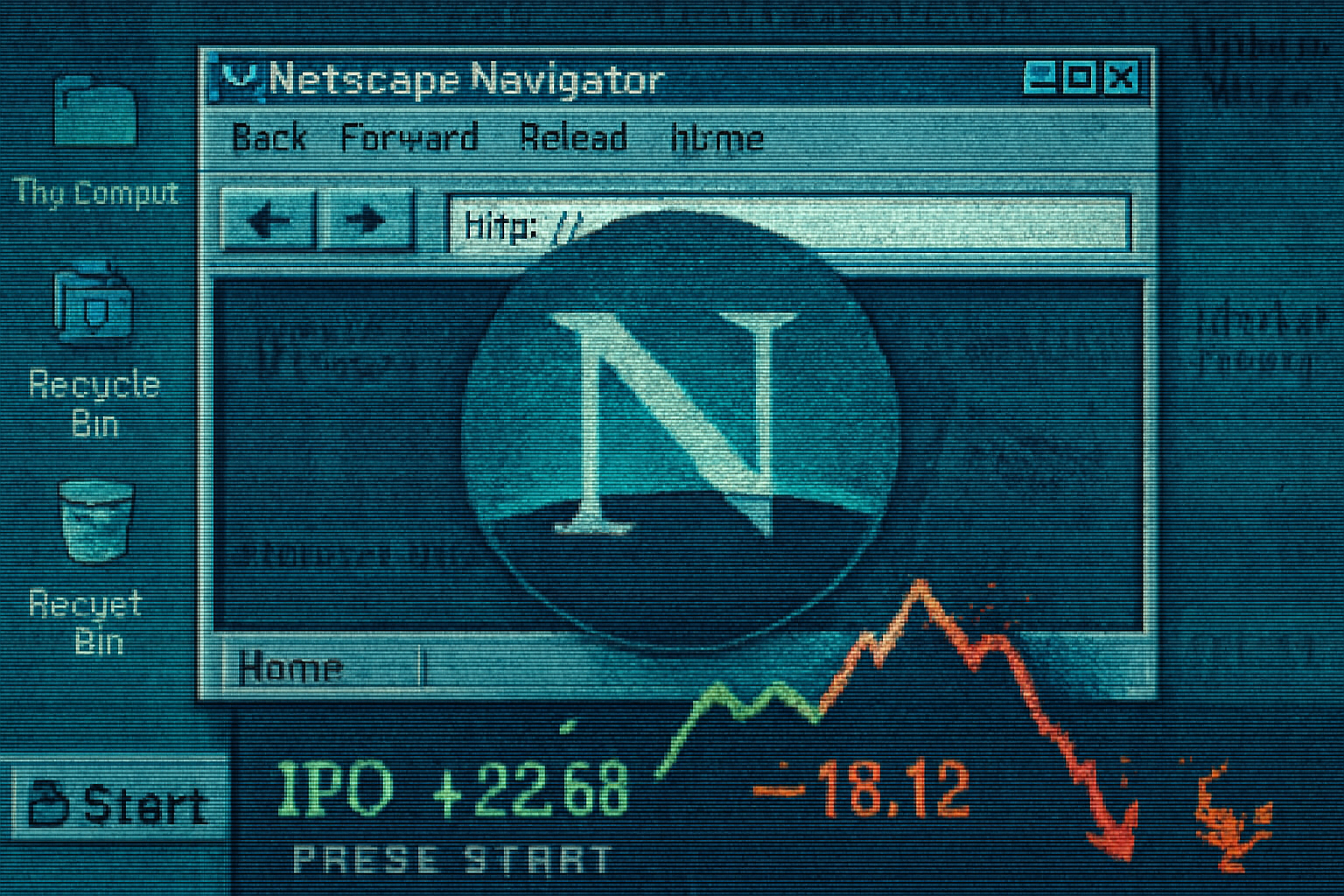

In 1994 a small company named Netscape released a product that made the World Wide Web usable for humans instead of scientists. People remember the blue “N” like a totem: it looked like the future. By 1995 Netscape’s IPO wasn’t just a financial event - it was a cultural one. Venture capitalists sprouted like mold. Startups believed they too could create the next unstoppable consumer gateway.

Netscape’s arc - breathtaking ascent, near-miraculous destiny, brutal decline - reads less like a tragedy and more like a case study in avoidable hubris. It also contains clean, brutal lessons for founders today.

The short, sharp ascent: why Netscape mattered

Netscape Navigator arrived at a precise moment: the web was a promising oddity, but it was slow, ugly, and fragmentary. Netscape made the web fast, pretty, and friendly. The company executed three critical moves early on:

- Product-led clarity - Navigator concentrated on user experience and standards support. It was faster, more stable, and embraced HTML features ahead of rivals. The browser lowered the activation energy for the web.

- Insane timing - The internet was transitioning from academic to commercial. Netscape captured attention at the exact hinge when consumers suddenly cared.

- The IPO spectacle - Netscape’s August 1995 IPO - which rocketed from a $14 opening price to $58 on the first day - transformed a company into a movement. That IPO seeded the dot-com funding mania and changed expectations about what software companies could command in public markets. See contemporary coverage for context:

Those elements combined into a runaway flywheel: press, developer love, user adoption, and capital.

Where Netscape slipped - and fast

The decline wasn’t a single catastrophic misstep so much as a cascade of strategic mistakes, bad incentives, and an irrelevant business model in the face of an existential threat.

1) Distribution beats product - especially against incumbents

Netscape produced a great browser, but Microsoft produced an unbeatable distribution advantage: Windows. Microsoft bundled Internet Explorer into Windows for free and made it trivially available to hundreds of millions of users. Bundling meant users didn’t have to go find and install anything. In platform battles, distribution is often the weapon of first resort.

Netscape’s response - patchy and reactive - couldn’t match that reach. The company underestimated how determinative control over the operating system would be.

2) No durable monetization

Netscape’s browser was free to users, and the company planned to monetize through complementary services (enterprise products, server software, and sponsorship). That strategy earned revenue, but not a moat. When the browser became a commodity, competitors could underprice Netscape’s services or replicate features. Having a killer product doesn’t absolve you from building a durable business model.

3) Platform dependency and lack of leverage

Netscape built its entire empire around client software that ran on someone else’s turf - Microsoft’s Windows. Dependence on an adversary’s platform is an existential vulnerability. The company lacked meaningful ways to force Microsoft to play by its rules.

4) Tactical misfires and internal politics

The company rapidly shifted between being an engineering-led startup and a public company subject to quarterly scrutiny. Leadership vacillated over priorities: speed vs stability, consumer vs enterprise, open web vs proprietary extensions. The transition from scrappy product shop to public corporation isn’t only cultural- it changes incentives, risk tolerance, and speed.

5) The open-source paradox

Netscape made a shocking move in 1998: it released the source for its browser (which later became Mozilla). That move was visionary in hindsight - it seeded what would become Firefox - but it was also an indicator Netscape was searching for answers, including community-driven innovation, after losing control.

6) Regulatory relief was too late

Microsoft later faced antitrust action that found it had used Windows to unfairly bolster Internet Explorer. But legal remedies are slow. By the time courts moved, the browser market had already consolidated and Netscape’s brand momentum had been bled out.

Useful summaries: Ars Technica on the browser wars and a broad Netscape history on Britannica/Wikipedia.

The decisive problem: a wonderful product on a borrowed stage

If there is a single thesis to extract from Netscape’s fall it is this: having the best product won’t save you if you don’t control distribution or the critical layer that decides who wins.

- Microsoft controlled the desktop OS. That control allowed it to weaponize distribution.

- Netscape, by contrast, relied on users taking an extra step - downloading and installing - an increasingly losing proposition when an incumbent removes that step.

This is where platform economics and strategic thinking matters more than immediate engineering triumph.

Lessons for today’s startups (the checklist that should be tacked to every boardroom wall)

Product-market fit is necessary but not sufficient

- Build something people love, yes. But map paths to customers that don’t assume users will cross a moat you don’t control.

Distribution planning must be explicit, not an afterthought

- If your product relies on another company’s platform, model scenarios where that platform becomes hostile. Play both offense and defense - diversify distribution channels and secure partnerships early.

Monetize in ways that create a defensible moat

- Advertising, subscriptions, platform fees, vertical specialization - each has trade-offs. Choose one that aligns with your core value and is hard to replicate.

Beware the lure of network effects that aren’t real

- Having many users is valuable only when users create value for each other (true network effects) or when scale creates cost advantages. Vanity metrics that flatter but don’t lock customers are a dangerous drug.

Compete with incumbents by changing the rules, not by head-to-head mimicry

- Don’t try to out-ship an incumbent on their turf. Invent new conventions, standards, or complementary services that shift where leverage lies.

Recognize when open source is a feature, not a business model

- Open-sourcing can catalyze adoption and community contributions, but you must pair it with viable revenue mechanisms (support, hosted services, premium features).

Legal redress is slow; product-level defenses are faster

- Antitrust relief can take years. Build product and distribution strategies assuming no regulator will save you in time.

Culture and incentives matter after IPO

- If you’re heading toward being public, align team incentives with the multi-year horizon and the operational rigor public markets demand.

Tactical examples for modern founders

If you plan to build on Apple or Google’s platform, assume the platform will prioritize its native service when convenient. Prepare a multi-platform play and own at least one customer channel (email lists, direct billing, device-agnostic client).

If you depend on a single large partner for distribution (mobile OEMs, social APIs), negotiate contracts that secure neutrality or compensation, and build fallback plans.

When releasing free consumer products, treat the product as the top of a funnel, not the whole company. Define conversion levers with concrete metrics.

Netscape’s redemption: what it left behind

Netscape didn’t die and vanish; it seeded Mozilla and Firefox, and it forced the industry to treat the web as a platform rather than an academic toy. The fight with Microsoft shaped antitrust thinking around digital platforms. In other words, Netscape’s corpse fertilized the next generation.

If you use Firefox today, you’re partly using Netscape’s DNA. And the public markets’ thirst for Internet winners - both glorious and foolish - can be traced back to that 1995 IPO.

Final diagnostics - a brutally frank summation

Netscape was an archetypal pioneer: it built a superior product at the exact moment the world needed it and then failed to build the fortifications that would preserve its position. It mistook early domination for unassailable advantage.

For founders: imagine you’re building the oxygen for a new ecosystem. Make it life-sustaining, yes - and also make sure you own the valves and the supply lines. A gorgeous browser is worthless if the house you live in locks the door behind the incumbent.

Netscape’s story is ennobling and cautionary. It’s proof that innovation without strategy is theatre; exciting in the moment, forgotten by history. And it’s also a reminder that sometimes the smartest thing a founder can do is plan like there will be a war for distribution - because usually, there will be.

References

- “Netscape’s IPO” - The New York Times coverage (1995): https://www.nytimes.com/1995/08/10/business/netscape-s-ipo-s-issue-sells-out.html

- Netscape history: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Netscape

- Browser wars retrospectives: https://arstechnica.com/features/2005/06/browser-wars/

- Timeline and acquisition - coverage of AOL’s acquisition (1998) - widely reported in contemporaneous press, e.g.,