· culture · 7 min read

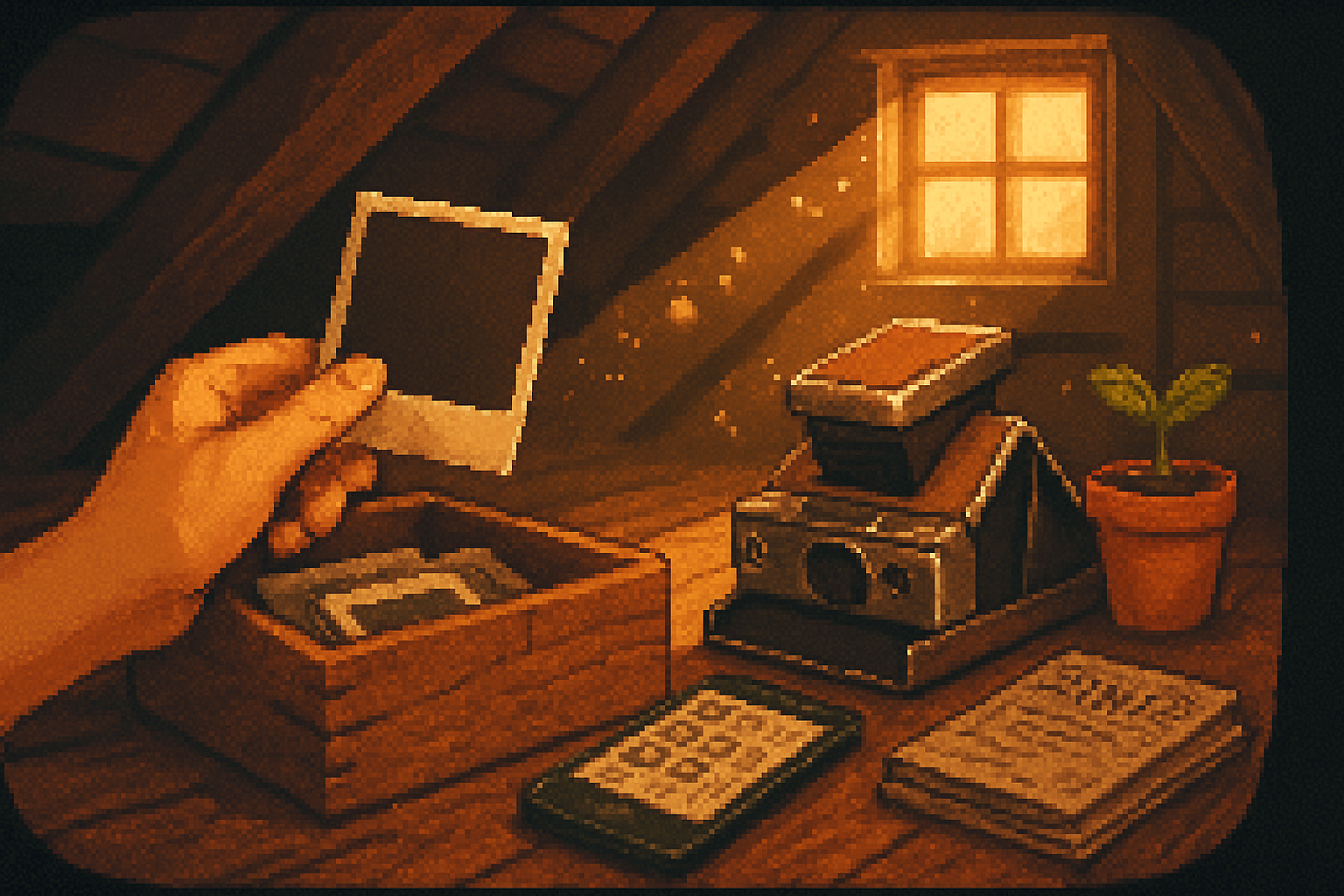

Reimagining Instant Photography: Are Analog & Digital Polaroids Due for a Showdown?

A close look at the emotional tug-of-war between classic instant film and the new generation of digital instant cameras - what each offers, what each takes away, and why the debate about authenticity is mostly about what we want photographs to be: evidence or relic.

It was at a rooftop wedding, the kind where the DJ is too proud of his playlist and the bar is inexplicably out of limes, that an argument about photography began without anyone realizing it.

The bride’s uncle - a man who still favors cufflinks and conspiracy theories - produced a battered SX-70 and, like a stage magician, peeled a square of white and watched it bloom into tone and memory. People crowded around. Smiles softened. Someone said, half-serious, “You can’t get this on Instagram.”

Across the room, a twenty-something with immaculate hair and a minimalist bag tapped her Instax and immediately tethered the same frame to her phone, slapped a filter on, and sent it to her Stories. She had more than 200 likes by midnight. Different economies of meaning. Same evening. Two Polaroids - and suddenly a small culture war.

Why does this feel like a battle? Because instant photography, once a mechanical novelty, has become a moral battleground about authenticity, nostalgia, and aesthetics.

A quick primer (because history matters)

Instant photography began as a technical marvel. The Polaroid Corporation popularized the format in the mid-20th century; its cameras produced single prints with a chemical process inside the frame. That tactile object - a photograph you could hold before you left the room - is the original instant.

The market splintered over decades: Polaroid formats (SX-70, 600, i-Type), Fujifilm’s Instax line (Mini, Square, Wide), and a recent resurgence that saw analog film return to vogue after the near-collapse of Polaroid’s original company (see a concise history at Wikipedia and contemporary coverage of the analog comeback in outlets like The Verge and Wired).

- Polaroid official: https://www.polaroid.com

- Polaroid Corporation history: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polaroid_Corporation

- Instax overview: https://instax.com/

- On the film revival: https://www.theverge.com/2017/3/20/14981646/once-dead-polaroid-instax-film-analog-photography and https://www.wired.com/story/film-photography-is-back/

Two species: what they actually are

Analog instant (classic Polaroid / Instax film)

- A chemical process inside a paper frame. The image develops in front of you - often unpredictably.

- The object is the product. The photograph has weight, texture, and a fixed border that signals “instant.”

Digital instant (digital cameras with instant printing, smartphone-to-lab devices)

- A digital sensor captures an image; a printer (thermal or dye-sublimation or Zink-style) ejects paper.

- The object is optional. You get files first, prints second - or never.

Polaroid has leaned into hybrid options too: the Polaroid Now+ and Polaroid Lab are attempts to bridge the two worlds by letting digital workflows print on analog-style film or controlling analog cameras with digital apps (see product pages for details).

- Polaroid Now+: https://us.polaroid.com/products/polaroid-now-plus

- Polaroid Lab and hybrid tools: https://www.polaroid.com

The emotional economy: why people care

Photography is a currency of trust. A photo can be evidence, souvenir, or performance. The debates about analog versus digital often sound like arguments about truth: is a chemical, slightly ruined image more “authentic” than a perfectly edited digital print?

Philosophers have long argued about the “aura” of art in the age of mechanical reproduction - Walter Benjamin famously described how reproduction changes the relationship to an artwork. Instant photos live inside that question. The analog print has an aura: accidental bleeds, warm shifts, and the physical slump of paper. The digital instant promises reproducibility, correction, and the kinder cruelty of algorithms.

- On the notion of aura - Walter Benjamin’s essay (context):

Pros & cons - the meat of the showdown

Analog instant (film)

Pros

- Tactility - You get an object immediately. It’s a souvenir, not just a file.

- Unpredictable beauty - Chemical quirks yield happy accidents - blown highlights, soft focus, color casts.

- Ritual - Peeling, waiting, and squinting is a social act. It makes people gather.

Cons

- Cost - Film is expensive per frame. Mistakes hurt more.

- Limited control - You can’t undo a blown exposure, and you can’t hand it over as a high-res file.

- Environmental impact - Chemical waste and single-use prints are an issue.

Digital instant (digital capture + instant printing)

Pros

- Control - Exposure, focus, and even basic editing before you print.

- Versatility - Keep files, print selectively, archive, and share instantly online.

- Cost per printed frame can be lower over time with affordable refill media.

Cons

- Less ritual - The magic is often moved into a tiny screen, and the print can feel like an afterthought.

- Manufactured nostalgia - Filters and presets mimic film, but critics call it fakery.

- Disconnect - If you always keep the file, the print loses scarcity - and some of its meaning.

Real user experiences (not the marketing blurb)

I spoke with three people (names anonymized):

- Mara, a wedding photographer, loves SX-70 film. “It forces you to slow down. You think about the moment because every shot counts.”

- Jonas, an influencer, prefers hybrid Instax/digital workflows. “I can make something that looks like film but also deliver a 4k image for clients. It’s the best of both worlds.”

- Rita, who runs a photo shop, says younger customers buy analog for aesthetic cred and older customers buy it for nostalgia; both leave with the same grin.

Common pattern: analog users talk about ritual and objecthood; digital users talk about control and utility. Neither side is purely ideological - both choices are pragmatic and performative.

Authenticity: the word everyone tosses around

Authenticity in photography is slippery. Are we praising an image because it’s “less manipulated,” or because it feels more sincere? Authenticity isn’t an objective property; it’s a social agreement.

- A worn Polaroid can signal honesty because its imperfections read as unedited truth. But the same effect can be deliberately manufactured by a filter - which raises the question - is authenticity about provenance (how the photo was made) or perception (how viewers interpret it)?

Expectations matter. A family photo printed on classic film carries a narrative: heirloom. A digital print from the same camera might be archived as data and never rediscovered. In a world drowning in pixels, scarcity - physical or social - becomes the new currency of authenticity.

Hybrid is not capitulation - it’s evolution

The interesting thing: the market is not dividing cleanly. Manufacturers and makers are inventing hybrids because human behavior resists neat categories.

- Polaroid and others produce devices that capture digitally but print on classic instant film.

- Smartphone apps and compact printers let users curate and only print what matters.

This is not a surrender of the analog. It’s a pragmatic acceptance that people want both: the shareability of digital and the ritual of the object.

The environmental and economic footnotes (because taste has consequences)

Instant film uses chemical developers and single-use substrates. Digital printing uses consumables too, but the ecological calculus is complex: mass digital storage consumes energy, while film processing produces waste. Neither system is innocent; both require reckoning.

Economically, instant film remains a premium product. That scarcity is partly why prints feel valuable. If you want cheap and throwaway, a smartphone will always beat a Polaroid for per-shot cost.

When to choose which (practical cheat-sheet)

- Choose analog film when - you want a physical keepsake on the spot, you want the ritual, or you value unpredictability.

- Choose digital/hybrid when - you need control, you want archives and high-resolution files, or you print selectively.

- Choose both when you - want the souvenir and the archive - shoot digitally, print one or two frames on film for special people.

Final jab: the showdown that isn’t a duel

If you imagined this piece ending in a fistfight - film slinging mud at digital in a smoke-filled room - you’ll be mildly disappointed. The truth is more mundane, and therefore more optimistic:

People want images that mean something to them. Sometimes that meaning comes from a chemical surprise and a thick white border. Sometimes it comes from the ability to tweak, save, and send. The formats will keep mutating because human taste is merciless, fickle, and brilliant.

Instant photography’s future will be plural. There will be analog purists and app-happy pragmatists. There will be printers that fetishize grain, and sensors that pretend they were born in a darkroom. The real victory is not one format erasing another - it’s that both push us to think about why we make pictures at all.

We make them to remember. To prove. To flirt. To keep. To lie, sometimes. And occasionally, to say to someone across a crowded room: hold this.

Because the photograph isn’t just an answer to a question; it’s the question itself.

References

- Polaroid company and products: https://www.polaroid.com

- Polaroid Corporation (history): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polaroid_Corporation

- Instax product line: https://instax.com/

- On the analog film revival: https://www.theverge.com/2017/3/20/14981646/once-dead-polaroid-instax-film-analog-photography and https://www.wired.com/story/film-photography-is-back/

- Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”: https://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/philosophy/works/ge/benjamin.htm