· culture · 7 min read

The Polyvore of Memory: How Polaroid Cameras Shaped Visual Storytelling in the Digital Age

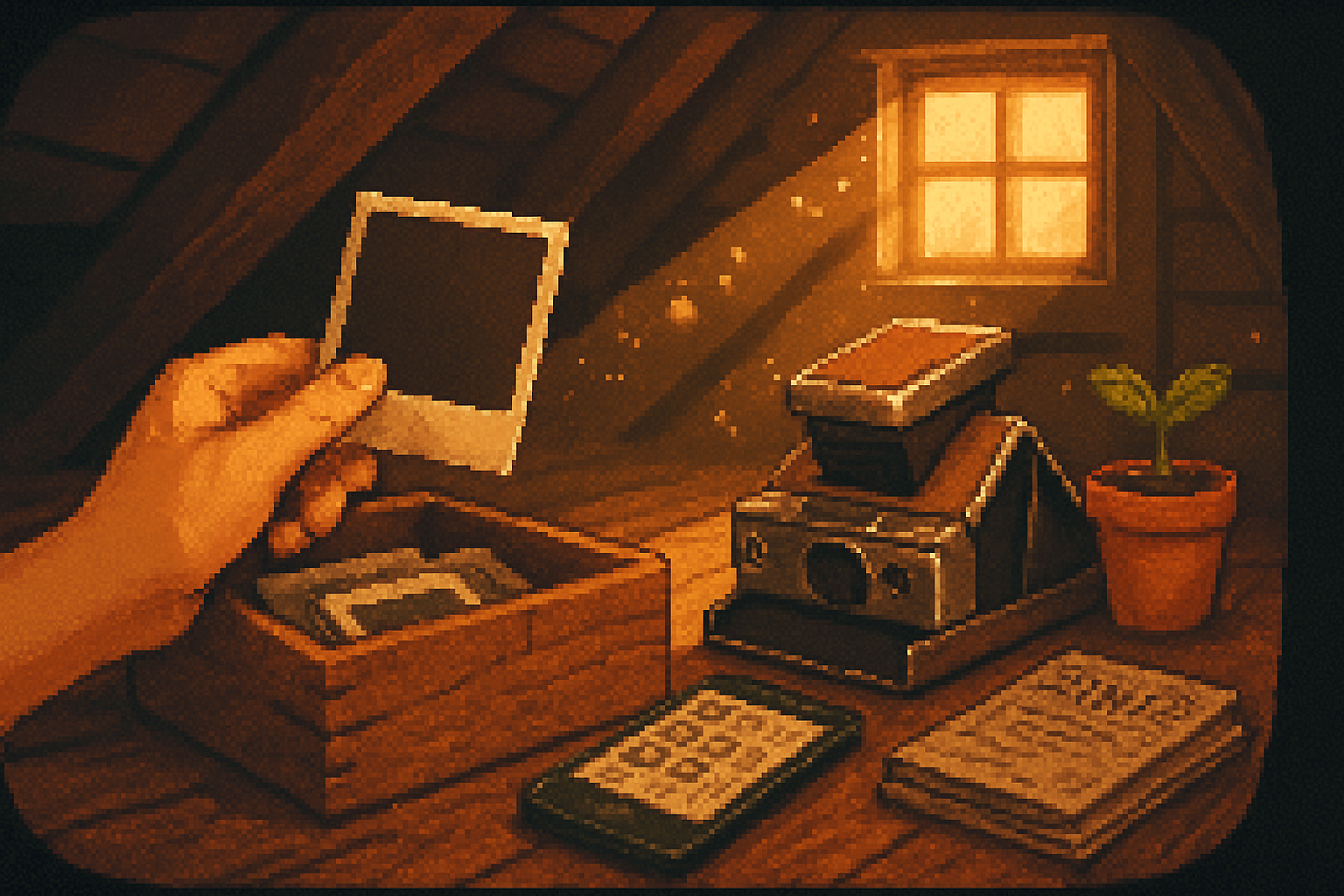

From the tactile thrill of a developing Polaroid to the curated scroll of modern feeds, instant cameras rewired how we make and share memories. This piece traces the Polaroid’s influence on aesthetics, narrative practice, and the persistent hunger for tangible authenticity in a pixelated world.

A small square, a slow reveal

You slide a glossy white frame from the camera, watch cloudy chemistry bloom into a face, a sunset, a laugh. For decades the Polaroid offered a kind of narrative punctuation - immediate, finite, and insistently physical. Today we tap, double-tap, and flick through thousands of images on a screen, but the visual grammar of our feeds owes a surprising debt to that instant moment of revelation.

This essay traces the path from tangible instant photography to the curated chaos of digital feeds, showing how Polaroids shaped contemporary visual storytelling - from aesthetics and ritual to an ongoing yearning for authenticity.

The Polaroid revolution: instantness as storytelling engine

When Edwin Land introduced the Land Camera and self-developing film in the late 1940s and commercialized the Polaroid system, he altered the temporal experience of photography. No longer did you hand film off and wait days to see results; the camera returned the object and the memory immediately. That temporal compression changed the relationship between maker, subject, and image.

Instant feedback made photography social and iterative - you could try a pose, see the result, and adjust. That loop encouraged experimentation and performative snapshots rather than formal documentation. See the Polaroid company history for a timeline of milestones:

The photograph was an object - small, framed, and ready to be held, gifted, or placed on a fridge - which turned images into micro-narratives and keepsakes rather than ephemeral data.

The square format and distinctive border created an immediately recognizable aesthetic that invited framing choices and a particular composition language. The classic SX-70, introduced in 1972, crystallized much of this visual identity: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polaroid_SX-70.

Aesthetics: grain, color shifts, and the charm of imperfection

Polaroids carried idiosyncrasies: muted midtones, color casts, vignetting, soft focus, and the occasional chemical streak. Far from being defects, these qualities communicated authenticity and mood. They suggested that moments were captured in the heat of experience - imperfect but true.

These visual signatures became culturally legible shorthand. A hazy sunset in a Polaroid meant warmth and immediacy; a slightly overexposed portrait signaled intimacy. That language translated easily into digital spaces where “filters” attempted to replicate the same imprimatur of livedness.

For more on the aesthetic and cultural history of instant photography, explore retrospectives such as the museum collections and entries that document its impact: https://www.moma.org/collection and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Instant_film.

Memory rituals: object, slip, and social gesture

Polaroids were often integrated into rituals: the instant donation at parties, a sticker on a scrapbook, a raw snapshot passed across a table. Their physicality encouraged tactile archiving. Instead of stellar resolution, value came from provenance - who had taken the photo, where it had been stuck, what scribbled note sat on the white border.

That white border itself became a storytelling device: people wrote dates, names, and one-line captions on the frame. A Polaroid was both evidence and memento; it served as a prompt for oral storytelling at reunions and gatherings.

The bridge to the digital: shape, gesture, and affordance

When social apps like Instagram launched in 2010, they inherited more than the idea of sharing images quickly. Instagram’s initial decision to adopt a square format echoed the Polaroid’s compositional constraints, which force a certain economy of framing and subject placement.[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Instagram]

Beyond shape, modern photo apps borrowed the Polaroid’s affordances:

- Immediate playback and frictionless sharing (the Polaroid’s instant reveal vs. the smartphone camera’s instant preview).

- Filters and borders that simulate chemical and optical quirks.

- A culture of snapshot-as-prop - images that perform identity, emotions, and lifestyle in a single frame.

Despite the differences - infinite storage, undo buttons, and easy editing - social media grafted analog sensibilities onto digital workflows.

The Polyvore parallel: collage culture and curated feeds

The essay’s title nods to Polyvore, the clothing- and mood-board platform that let users assemble swatches, looks, and aesthetics into single mood collages (active 2007–2018). Polyvore was essentially a digital scrapbook - a modern descendant of the shoebox of Polaroids - where fragments were arranged to tell a visual story about identity, aspiration, and taste. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polyvore

Social feeds function like endlessly scrolling Polyvores: each post is a swatch, each profile a mood board. The feed’s curation - the choice of color palette, the rhythm of posts, the interplay of candid and staged images - mirrors the way Polaroid collections once expressed personality through sequencing and juxtaposition.

Nostalgia, authenticity, and the algorithmic appetite

In a world dominated by algorithms and infinite reproduction, Polaroids promise something finite: scarcity, decay, and provenance. These qualities have become markers of authenticity. Digital culture seeks to simulate that authenticity through filters, faux-film presets, and “authentic” candid shots.

Nostalgia functions here as a design and social strategy. Polaroid aesthetics are often deployed to signal a sensibility - wistful, artisanal, human - that resists overproduction. Yet that signal can be commodified: branded campaigns and influencers often adopt Polaroid-like visuals to borrow credibility.

Scholars and cultural critics note that nostalgia is not merely longing for the past but a resource people use to negotiate identity in the present. See discussions around nostalgia and social media in popular and academic coverage, for example: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nostalgia.

Resurgence and remix: analog revival in a digital era

In the 2010s an analog revival blossomed. The Impossible Project (later rebranded as Polaroid Originals and then Polaroid) bought film production lines and kept instant photography alive, partly by tapping into the desire for tactile images: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polaroid_Originals

Young creators - digital natives raised on smartphones - began embracing analog for its slowness and materiality. They curated physical Polaroids in flat-lay photos, scanned them, and reintroduced those scans into digital feeds, creating a feedback loop where analog objects become digital signifiers of authenticity and mood.

Memory, curation, and the ethics of storytelling

Polaroids taught us how memory could be edited at the point of capture: choose the moment, frame it tightly, add a handwriting note. Digital platforms extend that power with infinite retakes and editing tools, but they also blur provenance and context. A Polaroid carries visible traces of its origin - who signed it, where it was stuck, its fingerprints - while a digitized image can be anonymized, replicated, and recontextualized endlessly.

This raises questions:

- What does it mean for memory when images can be endlessly manipulated and redistributed?

- How does scarcity (a Polaroid’s finite number) shape the value of an image versus the abundance of digital archives?

Thinking through these questions helps us understand both why Polaroid aesthetics remain attractive and why physical objects still matter.

Practical inheritance: how Polaroid rules show up in feeds today

Look closely at contemporary social feeds and you’ll notice Polaroid’s fingerprints everywhere:

- Square crops and centered compositions that emphasize people and objects at a human scale.

- Borders, film grains, and color shifts used as shorthand for intimacy or nostalgia.

- The use of physical Polaroids as props in photographs - scanned into feeds as evidence of analog authenticity.

- Collage and mood-board posts that arrange images to narrate a weekend, a relationship, or a brand identity (Polyvore’s legacy).

These practices are not merely aesthetic mimicry; they map how we continue to use images as narrative building blocks.

Conclusion: from instant object to infinite feed - a continuing conversation

Polaroids did more than produce pictures; they codified a way of seeing and telling. Their constraints invited creative choices; their materiality reinforced social rituals; their imperfections signaled truth. Digital platforms absorbed and transformed these lessons, creating new affordances but also new tensions between scarcity and abundance, object and data, memory and performance.

In the end, the Polaroid of memory is less a relic and more an ancestral grammar. Even as we scroll through curated chaos, we arrange images to narrate who we are - and we continue, almost instinctively, to borrow Polaroid’s tools: the square frame, the handwritten caption, the desire to make something that can be held.

Acknowledgments & further reading

- Polaroid Corporation - historical overview: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polaroid_Corporation

- Polaroid SX-70: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polaroid_SX-70

- Instant film and its cultural impact: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Instant_film

- Polyvore and the era of digital mood boards: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polyvore

- Polaroid Originals / The Impossible Project: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polaroid_Originals