· retrotech · 7 min read

Inside the VIC-20: A Technical Anatomy of a Vintage Computing Pioneer

The VIC-20 wasn't the most powerful machine on the block. It was the first computer to put a usable, inexpensive microcomputer into millions of homes. This article tears open the hardware and software of the VIC-20, explains the engineering compromises, and shows how severe constraints sculpted creative programming techniques that still inspire retrohackers today.

A boy sits on a linoleum floor, a rainbow of cassette tapes stacked beside him. He drops a tape into the Datasette, plugs in a joystick, and types LOAD ”*“,8,1 on a little beige keyboard. The screen flickers into a blocky promise: “READY.” That’s the scene repeated in living rooms and schoolrooms in 1980 and beyond - the moment the VIC-20 made computing domestic, accidental, and intimate.

Why care about a toy-like machine that by modern standards barely fits a Tweet? Because the VIC-20 is a machine of constraint - engineered to be cheap, modest, and wildly accessible. Those constraints forced engineers and programmers to invent. The result: a technical ecosystem full of clever hacks, hardware frugality, and lessons about economy that feel downright modern.

A quick orientation: what the VIC-20 actually is

- Released by Commodore in 1980, the VIC-20 was the company’s low-cost consumer machine and the first computer to sell more than a million units [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/VIC-20].

- Its heart was the MOS Technology 6502 CPU family - the same simple, fast, and frugal 8‑bit core that powered dozens of early micros [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MOS_Technology_6502].

- Video and a lot of the gadgetry lived in the MOS Video Interface Chip (VIC) - a single chip that handled text, colors, and rudimentary graphics for the machine [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/VIC_(chip)].

Read those three facts and you begin to see the product philosophy: reuse cheap silicon, consolidate functions into a few chips, and shave every cost to hit an unheard-of price point.

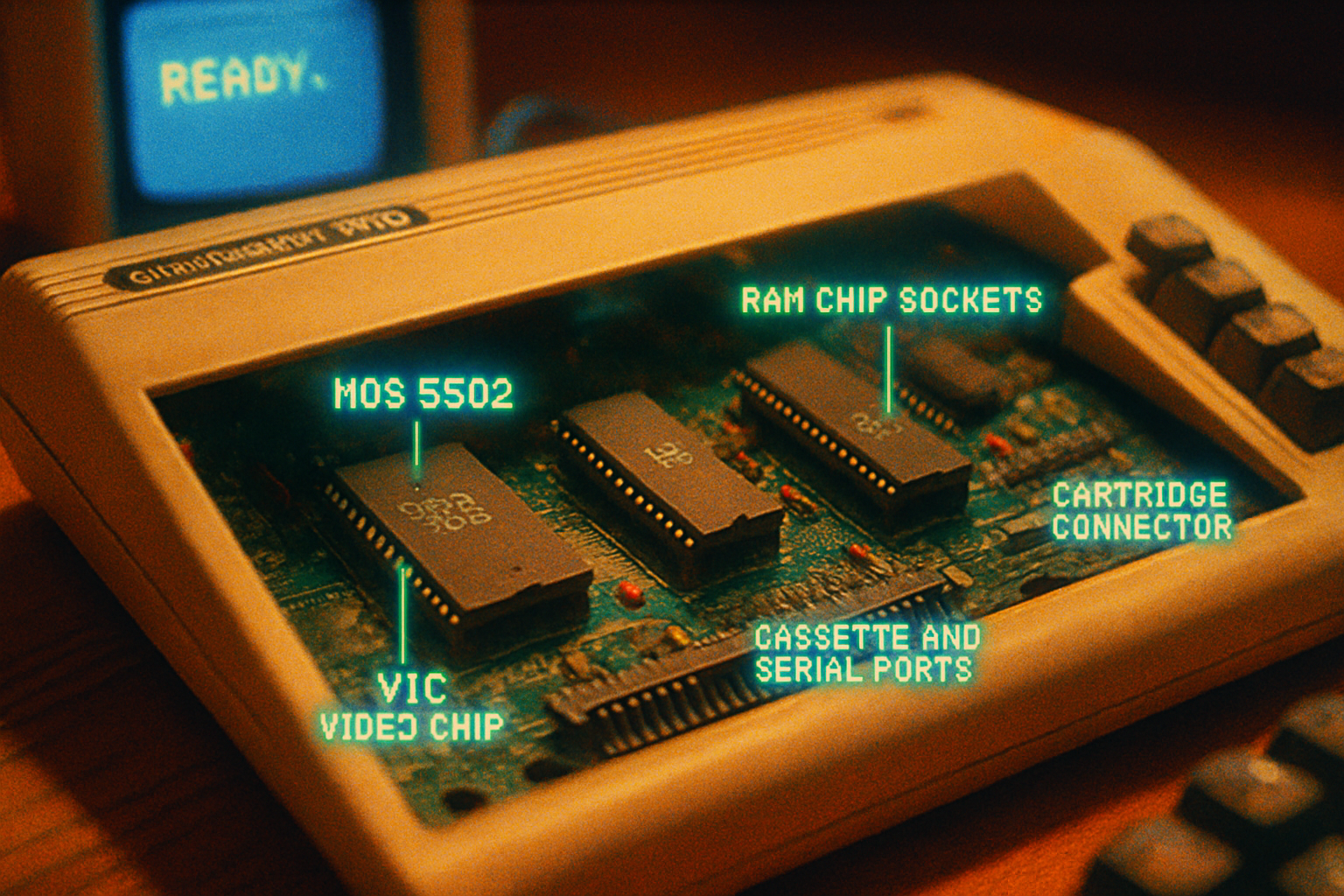

Hardware anatomy - the parts list and why they matter

CPU: MOS 6502 (≈1 MHz)

The VIC-20 used a 6502-family processor running at roughly one megahertz. The 6502 is a famously economical design: small instruction set, fast for its era, and easy to squeeze into tight loops. But “≈1 MHz” is the operative restriction: you cannot brute-force your way out of a performance problem.

Why that matters: the low clock forced careful cycle counting and compact code. Slow loops, on the other hand, taught novices how to think in clock cycles.

Video: the VIC chip (single-chip video)

The VIC video chip combined text rendering, color attributes, and a primitive capability to redefine character sets. Unlike the later SID+VIC-II architecture of the Commodore 64, the VIC was simple and cheap:

- Text-centric design with a narrow default column width - you could display fewer characters than on the later C64.

- Character-redefinition was the primary trick for animation - by changing the bitmaps in character ROM you could fake sprites.

- Color resolution and raster flexibility were limited compared to subsequent chips.

In short: the VIC made graphics possible, not easy. The trick was always to bend the character matrix to the will of your game.

Memory: tiny, precious, and modular

Out of the box a VIC-20 shipped with only a few kilobytes of RAM. In practice that meant only a few kilobytes were available to BASIC programs after the system and ROMs took their share. Hardware expansion was a first-class consideration: plug-in RAM cartridges were common and inexpensive.

Why it shaped software: small RAM encouraged tile-based graphics, reused level data, and streaming or procedurally generated content rather than full-screen bitmaps. It also encouraged cartridge-based distribution to bypass slow cassettes and limited RAM.

ROMs and I/O: BASIC, KERNAL, and the cartridge port

The machine’s firmware contained a BASIC interpreter (BASIC 2.0 in ROM) and a KERNAL - routines for I/O, serial communications, and disk/tape control. The cartridge port was more than convenience; it was an architectural escape hatch. Cartridges could map their code into the machine’s address space and override ROM routines. For developers that meant instant upgrades: fast-loading loaders, extra RAM via bank-switching hardware, and even new BASIC commands were possible via cartridge.

Audio: rudimentary tones

Sound on the VIC-20 was basic. The VIC chip could produce simple tones and noise - enough for bleeps, explosions, and the earworm jingles of early arcade ports, but nothing like the rich synth textures the later SID chip provided on the C64.

The software stack: BASIC, ROM, and assembly

BASIC 2.0 shipped in ROM. It was user-friendly and immediate: type, run, repeat. But it was also conservative and limited:

- Slow - interpreted BASIC at ~1 MHz is lethargic for games.

- Limited primitives - graphics and sound control were not part of the language in any robust way.

The consequence was obvious: performance- and graphics-sensitive code lived in 6502 machine code. Developers rapidly learned to write tight assembly routines, call them from BASIC, and orchestrate the whole show. That split - BASIC for orchestration, assembly for muscle - became a cliché of early micros.

Engineering constraints and the explosions of creativity they caused

Constraints are not a curse. They are a crucible. The VIC-20 generated a number of enduring hacks because its limitations made certain approaches inevitable.

Character redefinition == pseudo‑sprites

The VIC’s easiest graphics primitive was its text characters. If you could redefine those character bitmaps on the fly you could animate little shapes - the birth of pseudo-sprites. Teams of developers used character-grid tricks to animate large numbers of objects with tiny memory footprints.

Analogy: if a modern GPU is a paintbrush, the VIC was a chisel. You carve each pixel out of existing geometry.

Memory banking and cartridge ROMs

Because cartridge hardware could map new ROM or RAM into the CPU’s address space, developers used cartridges both as distribution and as runtime expansion. Bank-switching let small games present much larger worlds than main memory would allow.

Cycle-precise programming and raster timing

The VIC’s limited graphic abilities pushed programmers to work in raster time. If you wanted color splits, flicker control, or the illusion of more colors, you had to change registers mid-frame. That required counting cycles and scheduling code to execute on precise scanlines. It was workmanlike, unforgiving, and beautiful.

Data compression and content hygiene

With a few KB of RAM, every byte mattered. Games used run-length encoding, tile maps, and procedural content to represent levels and graphics. Code reuse was a necessity. Players rarely suspected how much compression labor went into those levels.

I/O workarounds: cassette vs cartridge vs disk

Slow cassette loading (and expensive disk drives) pushed vendors and hobbyists toward clever fast loaders, RAM-resident loaders, and cartridge-based solutions. The tape format cultivated patience - and a cottage industry of faster loader tricks.

A few concrete technical anecdotes

- Cartridge tricks - some vendors shipped cartridges that switched in extra RAM banks or replaced parts of the ROM. That let them ship larger games and utilities despite the tiny onboard RAM.

- The redefined-character sprite technique - by treating the 8×8 character cell as a sprite cell and updating the character bitmaps per frame, programmers achieved dozens of moving objects at acceptable frame rates.

- Raster tricks borrowed later by C64 devs - midline color changes and register tweaks performed during the electron beam’s draw cycle were prototyped and refined on machines like the VIC.

The VIC-20’s limitations as a teaching tool

There is a reason a generation of hackers learned on humble machines. The VIC forced you to think about: memory budgets, CPU cycles, and hardware timing. It made invisible system architecture visible. Learning on a machine where every cycle counts produces a kind of practical humility: you design within physics.

If modern education has a blind spot, it’s that abstraction is easy now. The VIC-20 made the abstraction visible and fiddlable. When you couldn’t call a library, you read the chip manual.

Legacy: modest hardware, outsized cultural effect

Technically, the VIC-20 is a curious footnote next to the later Commodore 64, but culturally it matters enormously. It was a people’s computer: cheap, repairable, and approachable. It taught hardware literacy at scale and created a market that rewarded low-level ingenuity.

And from an engineer’s perspective: the VIC is a masterclass in product optimization. It shows how to pare a design to the bone and still leave room for brilliance. You can measure progress in flops per second - but you can also measure it in how many people had their first messy, glorious encounter with code on a beige keyboard.

Where to read more

- The VIC-20 overview and history: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/VIC-20

- MOS 6502 microprocessor background: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MOS_Technology_6502

- The VIC video chip: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/VIC_(chip)

- Comparison and lineage to the Commodore 64: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Commodore_64

Final thought

The VIC-20’s genius wasn’t in raw specs. It was in a design that turned scarcity into a feature. When your machine is a miser, you become an artist of frugality. The hacks that came out of the VIC era are not quaint relics; they’re reminders that constraints can create clarity, and that ingenuity thrives when silicon says “no.”