· retrotech · 7 min read

The Influence of IBM PC AT on Today's Computing: A Deep Dive

How a 1984 business desktop - the IBM PC AT - seeded the rules, mistakes, and rituals that still shape modern PCs. A look at the technical choices (80286, 16-bit bus, BIOS setup, A20), the business model of compatibility, and the long shadow these decisions cast on hardware, OS design, and industry structure.

I remember the first time I saw an IBM PC AT live: beige monolith, a pair of full-height floppy drives, and stickers promising “286” as if the number itself conferred legitimacy. An engineer popped the case, tapped a rectangular chip, and said, with the bored affection of someone who’s auctioned away romanticism a dozen times, “This right here is why everything looks like this.”

That’s not an exaggeration. The IBM PC/AT (Model 5170), introduced in 1984, was not the first personal computer, nor the most elegant. But it was a pivot point: a combination of a new CPU, a new bus, a new set of configuration rituals, and-crucially-IBM’s imprimatur. Those elements codified conventions that reverberate into modern computing. If a modern PC is a cathedral, the AT laid a lot of its foundations: sometimes graceful, sometimes hideously patchwork.

What the AT actually brought to the party

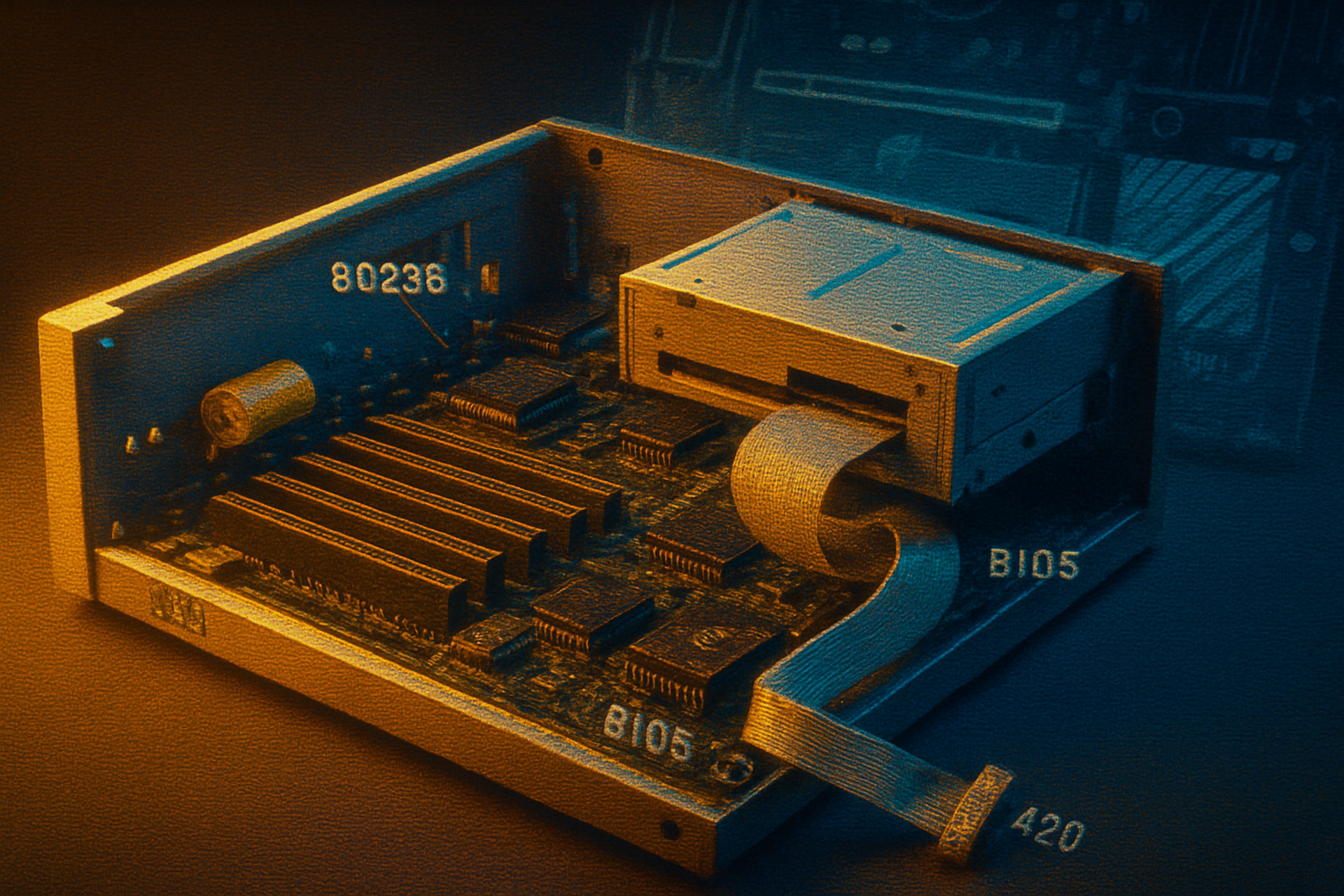

Short, practical list first. The PC AT introduced or popularized a handful of concrete hardware and system features that became defaults for decades:

- Intel 80286 CPU as mainstream PC silicon, bringing (limited) protected mode and the beginnings of more advanced memory management (Intel 80286).

- A 16-bit expansion bus (the AT bus), backward-compatible with the original PC/XT’s 8-bit slots-this evolved into the ISA standard that dominated PC expansion for years (Industry Standard Architecture).

- Battery-backed real-time clock and CMOS configuration storage with a BIOS setup utility-configuration moved out of DIP switches and into firmware-controlled menus (BIOS setup and CMOS).

- 1.2MB 5.25” floppy drives and support for larger media-an early move toward handling larger datasets on removable media.

- New firmware responsibilities - more BIOS services, and conventions (interrupt vectors, device numbering) that software would program against.

Each of those is unglamorous. But their dullness is the point: the AT preferred repeatable, programmatic interfaces over one-off hardware quirks. That preference is the essence of compatibility.

The technical legacies you still sit on

Here are several AT-origin choices that left fingerprints on modern systems.

1) The x86 line and the tyranny of compatibility

The 80286 didn’t invent x86, but putting Intel silicon at the center of IBM’s design guaranteed that future PCs would follow that lineage. Backwards compatibility with older code (real mode) became a sacrosanct property. The result: decades of design decisions shaped to accommodate ancient expectations. Today’s high-speed CPUs still toe a line between innovation and a stubborn obligation to run code written in the 1980s.

Reference: Intel 80286

2) Buses that invited third parties to flourish (and then ossify)

The AT bus-eventually standardized as the 16-bit ISA-made it easy for third-party vendors to add capabilities. That expansion-card economy powered an ecosystem: sound cards, video cards, SCSI controllers, network cards. It also institutionalized a hardware model where new capabilities were expected as add-ons rather than integrated functions.

This modularity was a strength and a curse. It let the market innovate quickly, but it left a residue of legacy pinouts, IRQ conflicts, and jumpers that persisted until the 1990s when PCI began to replace ISA (ISA bus history).

3) BIOS, CMOS, and the ritual of firmware configuration

Shifting configuration to a BIOS menu normalized a firmware layer as the system arbiter. Software-especially operating systems and installers-began to rely on BIOS services (interrupt calls, device enumeration). That dependency lasted so long that when it became time to move beyond BIOS, the transition to UEFI was politically and technically fraught.

Reference: BIOS

4) The A20 gate and architectural debt

A bizarre but revealing example of compatibility baggage is the A20 line. The 80286’s behaviour in protected mode meant that some programs depended on the 20-bit address wraparound of the original 8086. To preserve those programs, a hardware “A20 gate” was introduced so software could toggle the 21st address line. The A20 dance persisted into the Pentium era and required kernel-level and firmware tricks long after the original technical reason had vanished.

Reference: A20 line

5) Software-first expectations: BIOS calls, INT vectors, device interrupts

The AT’s BIOS defined software-facing hooks-interrupt vectors and services-that MS-DOS and early Windows exploited. That software-first expectation shaped OS design: the operating system had to play nice with firmware and interrupt assignments, and utilities often directly manipulated hardware because the abstraction layer was thin and voluntary.

How that architecture shaped business and industry structure

The technical story and the business story are mirror images. IBM’s design choices created an interface that software vendors and hardware manufacturers could target. Two consequences followed.

Compatibility as product strategy. The PC clone market-Compaq, Dell, and hundreds of smaller players-could enter because they could implement compatible hardware and BIOS behaviors. Loyal deference to existing interfaces lowered switching costs and made the “IBM-compatible” space a commodity market.

The rise of the platform company. Microsoft, Intel, and BIOS vendors (Phoenix, AMI) profited from the standardization. The platform was the prize, and compatibility was the moat. This dynamic is central to modern platform economics - be the base everyone builds upon, and you reap rents.

See: Compaq and early PC compatibles

Things we owe the AT-and things we shouldn’t

What the AT deserves credit for:

- It normalized an upgradeable, modular desktop model. Want a new graphics or network capability? Buy a card.

- It seeded a massive hardware and software ecosystem that drove prices down and innovation up.

- It proved the marketplace value of compatibility - an industry can standardize quickly when vendors have a common target.

What the AT saddled us with:

- Decades of compatibility baggage-software and firmware that must keep ancient behaviors alive at great cost.

- A culture of bolting new features on as optional cards instead of designing integrated, simpler systems (for better or worse).

- Firmware and boot complexity (BIOS legacy support) that slowed technical progress and added security headaches.

Concrete lines from the AT to your laptop right now

If you want a concise map of influence, here are direct lines:

- The x86 instruction set family (and its backward-compatibility constraints) comes through Intel chips that the AT helped cement.

- Expansion slot expectations evolved from ISA to PCI to PCIe-but the idea of a swappable peripheral card started with the AT’s bus model.

- Firmware-first boot and configuration (BIOS → UEFI) is a straight descendant of the AT’s BIOS/CMOS approach.

- Software ecosystems that rely on documented (and undocumented) firmware behaviors were born from early PC/AT-era practices. Device drivers, kernel-mode programming, and userspace tooling still reflect that heritage.

What the AT couldn’t foresee (and what saved us)

The AT’s model assumed extensibility by vendors and longevity of hardware interfaces. It didn’t foresee a few important pushes that changed the landscape:

- Integration - modern SoCs aggregate functions (graphics, storage controllers, Ethernet) that used to be discrete cards.

- Security-first firmware - the UEFI Secure Boot model (and signed firmware) is a reaction against the insecure, mutable BIOS world.

- New architecture alternatives - ARM and RISC-V pose real alternatives to x86’s compatibility calculus, especially in mobile and cloud.

Those shifts free designers from some AT-era constraints. But they also create new platform lock-in and new compatibility questions.

Final thought: compatibility is a moral and technical choice

The AT teaches a stubborn lesson - compatibility is a form of governance. It’s not neutral. When you prioritize backward compatibility, you preserve users and markets, but you also embed ancient compromises into the future. When you break compatibility, you enable cleaner, safer designs-but you force costly migration.

We celebrate the AT for the continuity it enabled: software that kept running, markets that could compete, and a hardware ecosystem that scaled. We curse it for the architectural debt it bequeathed: the A20s, the legacy BIOS support, the Byzantine IRQ tables.

If you boot a modern PC and curse at a firmware menu, a legacy driver, or an inexplicable compatibility flag, tip your hat to the AT. It gave us a machine that was useful, monetizable, and expandable. It also taught the industry an expensive lesson: standards win, but standards are sticky.

Further reading

- IBM PC/AT (Wikipedia): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IBM_PC/AT

- Intel 80286 (Wikipedia): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intel_80286

- Industry Standard Architecture (Wikipedia): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Industry_Standard_Architecture

- A20 line (Wikipedia): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A20_line