· retrogaming · 4 min read

The Game Gear vs. Game Boy: A Retro Matchup that Redefined Portable Gaming

When Sega’s vibrant, backlit Game Gear strode into the playground it looked like a knockout - until Nintendo’s stolid, battery‑sipping Game Boy kept the lights on and the sales steady. This is the story of how a dazzling underdog forced innovation, while a grayer champion won the war.

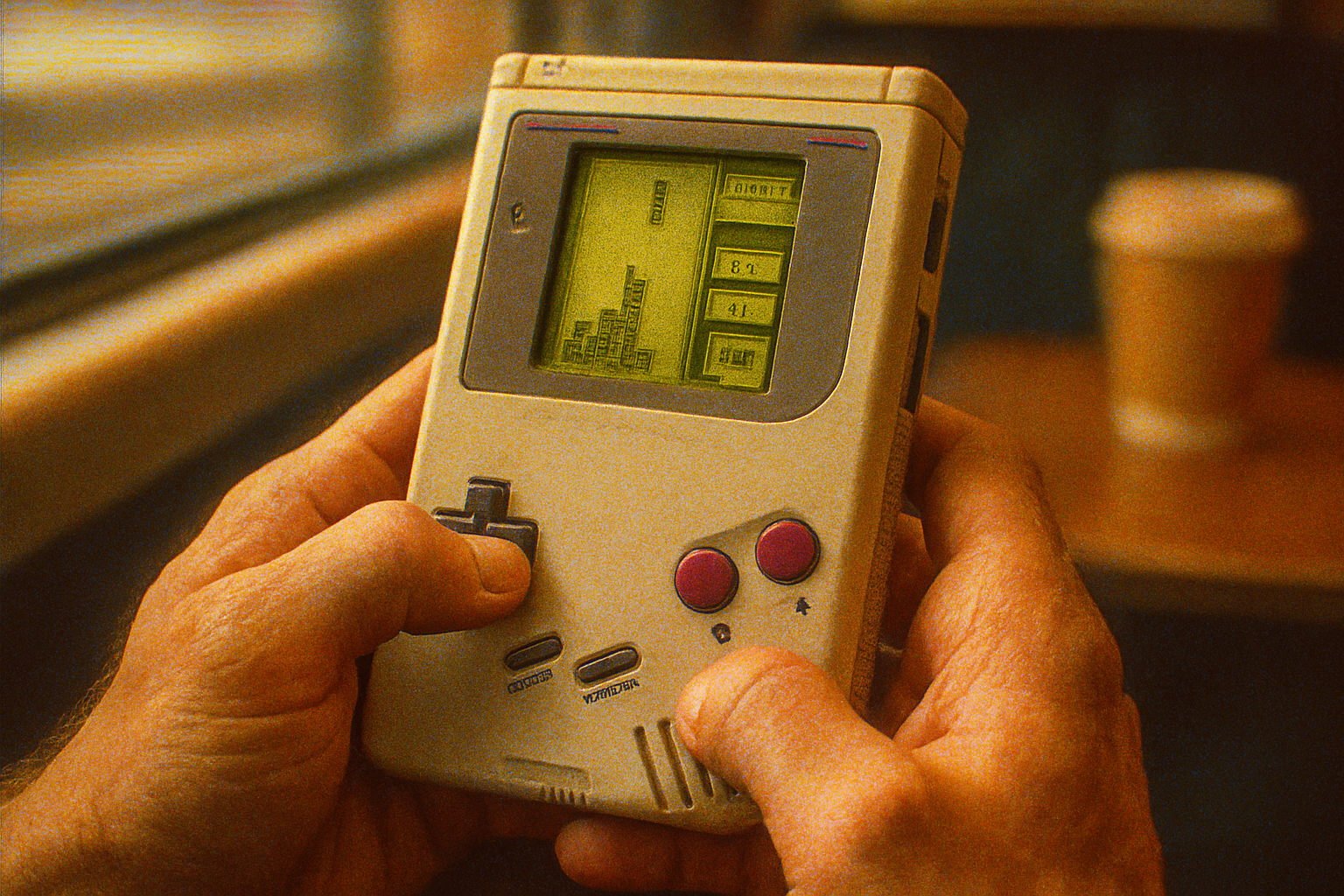

It started one summer afternoon on a schoolyard bench. A kid unzipped his backpack and turned on a Game Gear - the screen flared with color like a tiny neon billboard - and for a second everyone forgot algebra. Another kid, quieter, held up a Game Boy. No colors. No backlight. But he had Tetris. He smiled. The argument that followed was less about pixels and more about survival: which machine would outlast recess and, ultimately, the market?

That fight - color and flash versus endurance and clever restraint - is the heart of the Game Gear vs. Game Boy story. One was a showboat; the other, a workhorse. Both rewrote what portable gaming could be.

A quick timeline (so we don’t pretend this was a fair fight)

- Nintendo released the Game Boy in 1989 in North America (after Japan and Europe), pairing a simple monochrome screen with an addictive library and exceptional battery life. See the Game Boy entry for details Game Boy - Wikipedia.

- Sega answered in 1990/1991 with the Game Gear - a color, backlit handheld that basically put a tiny Master System in your hands. It dazzled. It drank batteries. More at

If the Game Boy was a pocket ledger - sober, durable - the Game Gear was a pocket cinema: brighter, heavier, and thirstier.

Hardware and the obvious tradeoffs

Sega’s pitch was simple: give players what home consoles could not - color, brightness, and arcade-ish fidelity. The result:

- Color, backlit screen that made sprites sing. It also meant short battery life (a few hours on six AAs), significant weight, and costlier manufacturing.

- Close architectural ties to the Master System made ports easier - a tactical advantage for Sega’s library.

Nintendo’s priorities were the opposite and profoundly pragmatic:

- Monochrome, non-backlit screen but exceptional battery life (often double or more than competitors), simple and rugged hardware, and a bargain price.

- A focus on gameplay and a launch library built around addictive, low-barrier experiences (start playing in seconds; no flashy tutorial required).

The irony: the Game Gear gave players something they wanted immediately (color), while the Game Boy gave them something they’d want later (long play sessions, a lower cost of ownership). Neither approach was morally superior - just strategically different.

Libraries: what played mattered more than how it looked

Here’s where the story gets cultural rather than technical. A handheld’s worth is measured not by pixels but by what people do with them.

Game Boy strengths:

- Phenomena like Tetris and later Pokémon (which exploded on the Game Boy, though Pokémon’s surge came later in the system’s life) turned the Game Boy into a social object. Tetris didn’t need color - it needed to be irresistible.

- A huge range of third‑party support and a knack for bite-sized, repeatable gameplay that fit commutes and recess.

Game Gear strengths:

- Strong Sega and Master System ports - Sonic the Hedgehog’s Game Gear version offered its own level design and pacing and showed how console sensations could be rethought for handheld constraints.

- Niche and arcade titles - Columns, Shinobi adaptations, and RPGs like Shining Force Gaiden - gave the system texture - not just flashy ports but experiments in how to translate console ideas into small screens and short bursts of play.

Game Gear’s library mattered because it forced developers to adapt and innovate. Seeing Sonic on a tiny screen wasn’t just fan service; it demanded different level layouts, tighter control design, and new thinking about pacing. In other words, limitations bred creativity.

Innovation born of constraint: how the Game Gear influenced game design

If Game Boy taught designers to make simple mechanics sing, the Game Gear taught them to make spectacle economical.

- Porting for scale - Developers learned how to preserve a property’s identity (speed, rhythm, personality) in a radically smaller, battery‑limited package. Sonic’s handheld iterations are great case studies: the levels are shorter, enemies arranged differently, and momentum is managed to fit quick sessions.

- Hybridization - Facing hardware limits, teams blended genres (puzzle elements inside action stages, bite‑sized RPG progression) to keep players engaged between battery swaps.

- Accessory experiments - Sega didn’t stop at color. They shipped add‑ons - a TV tuner, and even adapters to play Master System titles - that pushed the idea that handhelds could be nodes in a larger entertainment ecosystem.

Those experiments influenced how publishers thought about handhelds. Color and higher fidelity were inevitably coming; Game Gear showed they were desirable. Nintendo’s later offerings (Game Boy Color, Game Boy Advance) can be read as responses shaped in part by Sega’s audacity.