· retrogaming · 6 min read

Atari Lynx vs. Game Boy: The Battle for Handheld Supremacy

A blade‑sharp contrast between flash and staying power: the Atari Lynx dazzled with color and technical ambition; the Game Boy won the war by being dull, durable, and brilliantly practical. A detailed look at why.

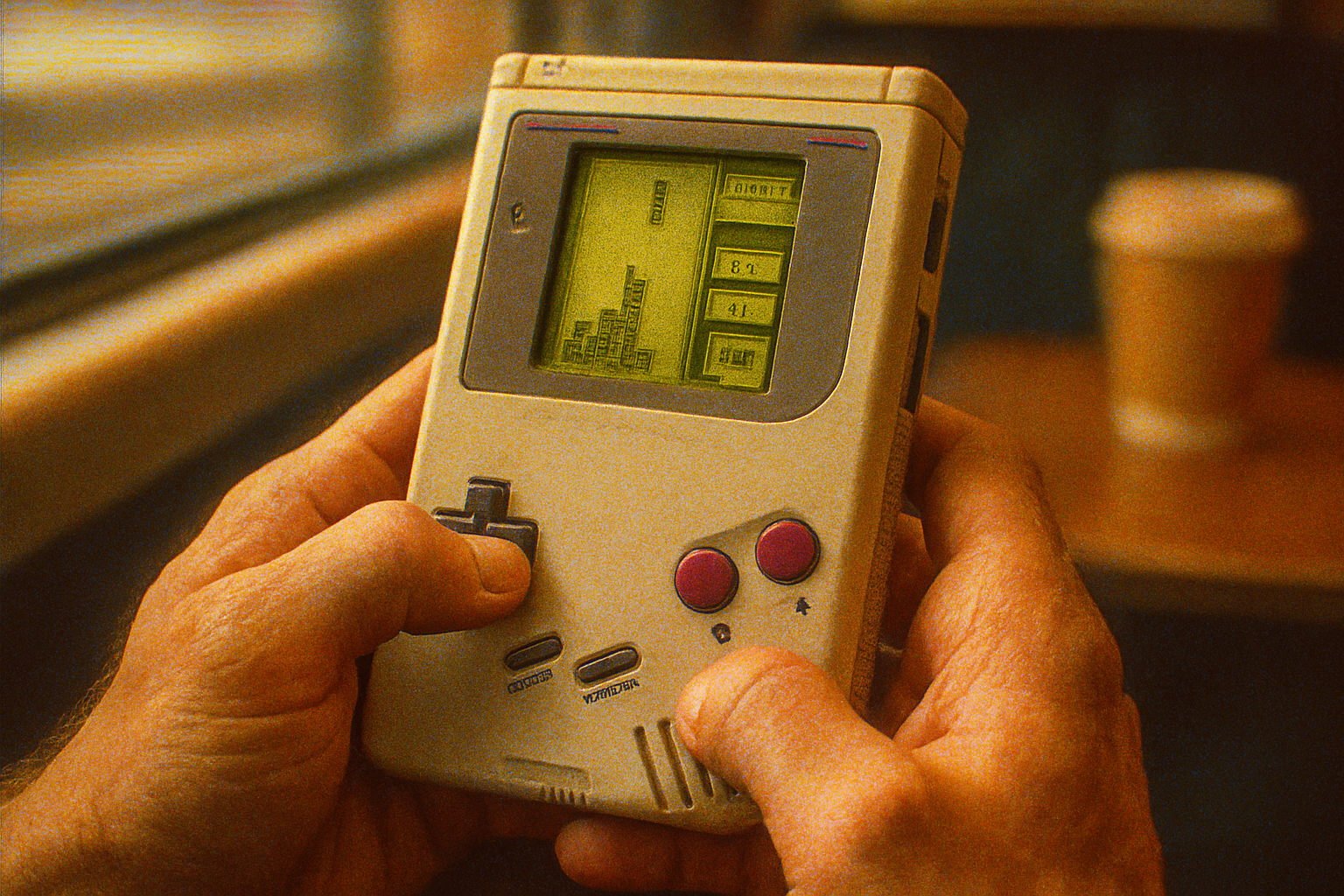

It begins with a toy-store moment: a glossy, color screen flashing polygonal explosions in a cramped Zanussi display, and beside it an anonymous gray brick quietly looping Tetris. Kids gravitated toward the color. Parents bought the gray brick.

The Atari Lynx and Nintendo Game Boy are the classic study in design tradeoffs: spectacle versus stamina, ambition versus pragmatism. One is the flashy prodigy who insists on wearing sunglasses indoors; the other is the bland, reliable friend who outlives the fad and collects the money. This is their story - technical bones, software muscles, and the market gravity that decided which handheld era we remember.

The opening gambit: launch, price, and positioning

- Atari Lynx - Debuted in 1989 after development by Epyx and release under the Atari name. It arrived as a premium, technically aggressive handheld with a color backlit LCD and features seldom seen in portable devices at the time.

- Nintendo Game Boy - Also released in 1989 (Japan first), but with a radically different philosophy: simple hardware, monochrome screen, excellent battery life, and an affordable price point. Nintendo paired the device with hugely accessible software (most famously Tetris).

You can sum up the differences like this: Lynx shouted “Look at me!” Game Boy whispered, “I will still work when the batteries run out.” The whisper won.

Hardware comparison - ambition versus economy

Both systems were marvels of engineering for their time, but aimed at different problems.

Display

- Atari Lynx - A full-color, backlit LCD that could render far richer visuals than the Game Boy. It supported hardware tricks (sprite scaling and rotation) that gave it arcade-like effects on the go.

- Game Boy - A reflective monochrome screen (four shades) with no backlight. The tradeoff: vastly superior battery life and visibility in daylight.

Processing

- Atari Lynx - Built around a custom 16‑bit chipset with dedicated graphics support, giving it advanced sprite handling and blitter-style features uncommon in handhelds.

- Game Boy - Used a modest 8‑bit Sharp CPU (the LR35902 family) running at a few megahertz - quite constrained but optimized for efficiency and low cost.

Power and portability

- Atari Lynx - Power-hungry display and more complex internals demanded bigger batteries; play time was measured in hours.

- Game Boy - Low power draw, conservative hardware choices, and simpler display meant long battery life (often double-digit hours on a set of AAs).

Ergonomics and durability

- Lynx had a unique ambidextrous layout and a broad, comfortable shape - it looked and felt like a modern handheld.

- Game Boy’s boxy shape and simple D‑pad made it utilitarian and hard to break. That mattered for a device meant for schoolyards, pockets, and the occasional fall off a car seat.

Put bluntly: Lynx was a technological statement; Game Boy was a logistical masterstroke.

The screen is not the only thing you see: software libraries and “killer apps”

Hardware can only do so much without software that exploits it - or software that sells it.

Atari Lynx notable titles

- Blue Lightning (tech demo turned launcher)

- California Games, Rygar, Electrocop, and Chip’s Challenge - many of which showed off the system’s color and scaling capabilities.

- Strong arcade ports and a handful of exclusive gems, but a small overall catalog.

Game Boy notable titles

- Tetris (the strangest and most consequential bundling decision in gaming history) - a puzzle game that appealed to non-gamers and made the Game Boy a must-have.

- Super Mario Land, The Legend of Zelda - Link’s Awakening, Kirby’s Dream Land, and a flood of third‑party titles later including Pokémon - all of which expanded the audience beyond early adopters.

Killer app lesson: a good library helps, but a single ubiquitous, addictive juggernaut (Tetris) bundled with an inexpensive, portable device will sell more hardware than great graphics.

Marketing, distribution, and the business end of the war

Nintendo played the long game - keep costs down, secure key software (and control licensing), and build a portable ecosystem. Tetris as a pack-in and an aggressive pricing strategy were decisive.

Atari (and Epyx) bet on wow factor to create a premium market. The Lynx was expensive to buy, expensive to support with cartridges (and production costs were higher), and late to secure consistent third‑party pipeline and marketing muscle.

The result was predictable: the Game Boy’s installed base grew quickly, attracting even more third-party developers, while the Lynx struggled to develop that virtuous cycle.

What the numbers (and history) tell us

Numbers are messy, but the arc is clear.

Nintendo’s Game Boy family would eventually dominate handheld sales and spawn a cultural phenomenon that included Pokémon, a multimedia empire, and a multi‑decade legacy. The Game Boy brand (including later Color and Pocket revisions) moved tens of millions of units worldwide (Game Boy - Wikipedia).

The Atari Lynx, for all its engineering daring, sold only a fraction of Game Boy’s numbers. It remains a beloved niche machine among collectors and retro-enthusiasts, admired for what it tried to do more than for what it ultimately achieved. Atari Lynx - Wikipedia

The takeaway: market inertia, price accessibility, and software breadth trumped technical spectacle.

Design philosophy as cultural statement

Nintendo’s approach was almost Puritan: limit features, lower costs, maximize playtime. This made the Game Boy a secular object of utility: you used it because it worked, everywhere.

Atari’s Lynx was decadent by comparison: it asked you to prioritize visual fidelity and innovation - aesthetics before pragmatics. It’s the product a designer writes home to brag about; it’s not the product a parent buys to placate a squalling child on a flight.

Legacy - who “won,” and what each console left behind?

Game Boy’s legacy

- Established the template for mainstream handheld consoles - battery economy, affordable price, strong third‑party support, and portable-friendly game design.

- Spawned franchises, influenced mobile gaming’s focus on accessibility, and remained culturally dominant through the 1990s and early 2000s.

Lynx’s legacy

- A reminder that innovation in handhelds wasn’t linear. The Lynx foreshadowed future priorities - color displays, more powerful silicon, and hardware-assisted effects that later consoles embraced.

- Today, the Lynx is a badge of nerd cred. Its influence is visible in later handhelds that tried to marry power with portability (some successful, some not).

In short: Nintendo won the market. Atari won admiration.

Closing: the moral of the handheld story

There’s a simple moral here: winning a format war is less about the most impressive specs on paper and more about the weakest link in the chain: cost, battery life, software breadth, and timing. The Lynx lost because a portable needs to be portable: it must be carried, used in sunlight, survive rough hands, and be affordable enough that enough people buy it to attract more developers.

The Lynx remains a beautiful, tragic experiment - the kind engineers write love letters to. The Game Boy is the boring, reliable friend who turned out to be the better investment. Both deserve respect: one for daring, the other for enduring.

References

- Atari Lynx - Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atari_Lynx

- Game Boy - Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Game_Boy

- Tetris (Game Boy) historical notes and bundling significance: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tetris