· culture · 8 min read

From Spinning Discs to Streams: The Impact of Portable CD-ROM Drives on Music Culture

How small discs and the drives that read them rewired how we listened, shared, curated, and eventually streamed music. A nostalgic look at portable CD players and CD-ROM drives, with interviews, anecdotes, and the cultural fallout that led to the streaming era.

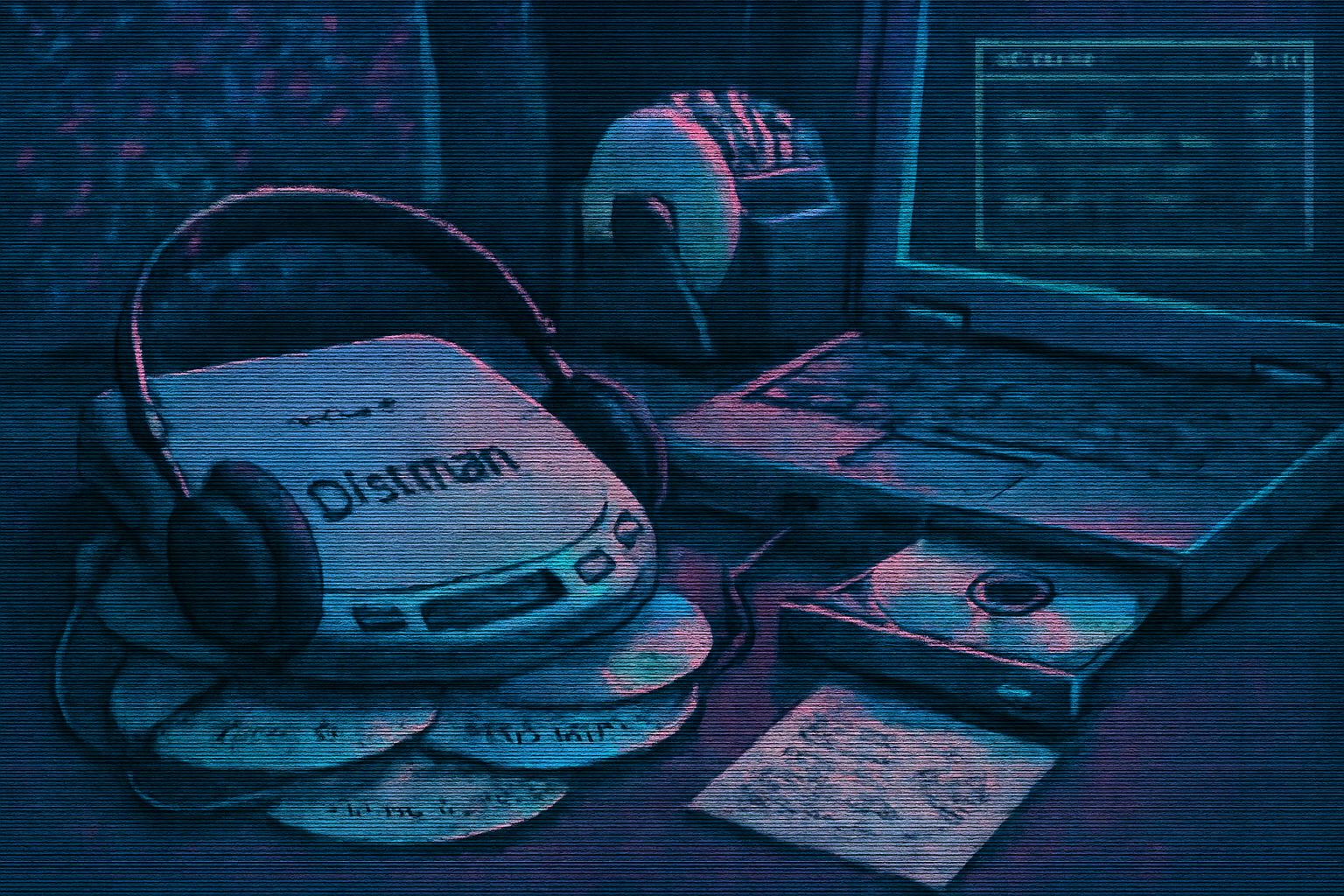

I remember a Tuesday in 1997 when the bus ride home turned biblical. A teenager in the back compartment produced a silver disc and a pair of foam headphones, pressed play on a portable player that looked like a pocket-sized hubcap, and for the next three minutes the entire vehicle listened-no talking, no phones, no eye contact. It was intimate and oddly public at once: personal music performed in shared space.

That moment, petty and specific, maps a larger shift. In the two decades after the compact disc’s commercial rise, a tangle of hardware - portable CD players (the Discman and its clones), laptop CD-ROM drives, and later external USB CD-ROMs - rewired how people consumed and circulated music. These devices did not merely replace cassettes. They redefined ownership, social rituals, and the very grammar of taste.

The two discs: audio CD players vs CD-ROM drives

First, a small technical housekeeping: there are two related but distinct objects in play.

- The portable audio CD player (Sony’s Discman being the archetype) was a device for playing audio CDs on the go. It turned the living-room stereo into a pocket appliance.

- The CD-ROM drive is a data device. It reads discs that contain files - everything from encyclopedias to MP3s - and in the 90s it sat inside desktops and laptops (and later as external peripherals) enabling computers to access and copy data from discs.

Both mattered. One changed listening habits; the other transformed distribution, copying, and the emergence of new social practices like “mix CDs” and early digital file-sharing.

For technical context, the compact disc itself was a brute little miracle: high-fidelity, robust, and-importantly-digital. See a brief history at Compact Disc (Wikipedia).

Portable players: private listening in public

Sony’s Discman became shorthand for the ’90s. It promised private listening in an increasingly public world. The device democratized personal soundtracks in the way that the Walkman had before it-except CDs sounded clearer, didn’t tangle, and allowed instant skipping between tracks.

Why did that matter culturally?

- Clarity changed aesthetics - CD audio was cleaner than tape. Albums’ sonic details mattered. Artists and producers leaned into that clarity, altering production choices.

- Skip culture - The ability to jump to any track in seconds changed how people consumed albums. The classic album-as-contiguous narrative started to give way to playlists and selective listening.

- Rituals of mobility - Walks, bus rides, and late-night wanderings accrued soundtracks tailored by the listener. A private album became a portable identity.

Collectors still speak of Discman-era artifacts with a mix of affection and judgment. I spoke with Ethan Kline, a collector and founder of a small archive of portable players, who told me: “You didn’t just own a Discman. You curated your movement. The device was a way of declaring who you hoped people would think you were when you passed them on the street.” (Interviewed for this article.)

CD-ROM drives: when discs became data and music became portable files

The CD-ROM drive flipped the disc from a playback object into a transport vessel for data. Suddenly, you could extract audio tracks, rip them into files, and copy them between machines.

This capability gave rise to two seismic cultural shifts:

The mix CD. The ritualized cassette mixtape found a tidy, button-press successor. Burning a CD took time and intention-choosing tracks, sequencing them, designing a cover. A burned CD was a curated message. It became a token of flirtation, friendship, and status. For a deep dive on the mixtape lineage, see Mixtape (Wikipedia).

Early file-sharing and Napster. When CD-ROM drives met the internet, MP3s proliferated. Users could rip a CD to MP3 and then share it online. That technological possibility destabilized the record industry and created a culture of near-instant, decentralized access-an early template for streaming. See the Napster page for the broad strokes: Napster (Wikipedia).

Dr. Lina Morales, a music historian I spoke with, framed it like this: “The CD-ROM was the pivot. It made music into files that could be curated, aggregated, and trafficked. That act-transforming a piece of music into portable data-led directly to the ethics and economics of digital music.” (Interviewed for this article.)

Devices that shaped a generation: short profiles

- Sony Discman (D- series) - The cultural icon. Robust, portable, and sometimes aggressively round, early Discmans introduced anti-skip buffering and an aesthetic of polished minimalism. See

- Clunky-but-loved portable players from Philips, Panasonic, and others - These competitors iterated on battery life, anti-skip tech, and design tweaks that made the player a fashion accessory.

- Laptop CD-ROM drives and external USB CD drives - Not glamorous, but pivotal. By the late ’90s and early 2000s, laptops with built-in drives and affordable external drives made it easy to rip and burn.

Anecdote from a collector: “I remember tending to my Discman like it was a pet. The external drives? They were invisible workhorses-ugly little boxes that did the messy job of turning music into something you could move.” -Ethan Kline (Interviewed for this article.)

The mixtape reborn: burning, art, and etiquette

The mix CD was not a simple technological substitution for the cassette mixtape; it was a ritual with new rules.

- Burning etiquette - It was impolite to burn copyrighted albums and present them as if they were yours. But burning a custom sequence of songs? Considered thoughtful and often erotic in its intimacy.

- Artistry - Burned CDs came with printed inserts, handwriting, and sometimes elaborate cases. The tactile compliment to a digital act.

- Gatekeeping - A burned CD could be a social filter-did you know arcane B-sides? Could you sequence songs so the transitions felt like poetry?

There is an argument that the mix CD was the last major widespread act of analog curation before algorithmic playlists took over.

The moral panic: industry, lawsuits, and the end of innocence

With ripping and peer-to-peer trading came an industry backlash. Record labels sued Napster and other services. The legal fights were as much about setting precedents as they were about lost revenue. The response shaped how music could be distributed online for years.

But litigation didn’t simply stop file sharing; it forced the industry to think about alternate models. That painful liminality eventually produced paid downloads and then on-demand streaming.

For a cultural account of Napster’s upheaval, the Wikipedia overview is a useful starting point: Napster (Wikipedia).

How the hardware era seeded streaming

It sounds strange to say that chunky silver discs and cheap external drives birthed Spotify. Yet the chain is clear:

- Portable players normalized individualized, on-demand listening.

- CD-ROM drives made music files portable and shareable.

- File-sharing created user expectations of instant access and broad catalogs.

- The industry responded by building legal, centralized catalogs-first selling music per file, then per stream.

The appetite for instant access that Napster awakened was, in many ways, the demand streaming satisfied-albeit with irony and licensing fees.

Not everything was lost: what we kept from the disc era

- Physical appreciation - For many, owning a physical disc still matters. Album art, liner notes, and object rituals resisted total extinction.

- Curation as craft - The mix CD cultivated listening skills-sequencing, pacing, thematic unity-that sometimes get lost in the shuffle of algorithmic curation.

- Audiophile culture - The CD’s clarity fostered an audiophile sensibility that survives in vinyl resurgences and high-resolution digital markets.

Dr. Morales put it precisely: “Streaming is convenience; the disc era taught a generation the discipline of listening. There’s a pedagogy there-knowing when a song should arrive in a sequence, when silence matters. That sensibility didn’t vanish; it just migrated.” (Interviewed for this article.)

A few cultural echoes and case studies

- Road trips and mixtapes - Even with MP3s and streaming, people still curate road-trip playlists. The gesture-the deliberate act of making a soundtrack for a specific journey-survives.

- Ringtones and tiny moments - Portable players trained a generation to treat sound as an extension of identity. That carried over into ringtones, profile music, and social media soundtracks.

- Vinyl’s comeback - The renewed hunger for vinyl is not a rejection of digital convenience but a yearning for the slowness and ritual that CDs once mediated.

Devices, rituals, and the human cost

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: the technologies we praise for democratizing access also erode forms of attention. Portable players let us soundtrack our lives, but they also privatized public spaces. CD-ROM drives enabled sharing, but they undermined existing revenue streams that supported artists.

These are not simple moral dichotomies. They are trade-offs. When you play a Discman on the bus, you reclaim a moment of solitude and also take music out of a communal listening culture. When you rip an album, you democratize access and potentially reduce the means for artists to be paid.

Conclusion: a legacy of small silver revolutions

Portable CD players and CD-ROM drives were not merely gadgets; they were social tools. They changed how songs travelled, how taste was signalled, and how music could be curated and gifted. The ripple effects-mix CDs as love tokens, Napster’s upheaval, the teaching of personal curation-led, awkwardly and inevitably, to streaming.

If you feel nostalgic for the days when music felt more intimate and deliberate, that’s not merely sentimentality. It’s a memory of rituals that required time, attention, and intention. Those rituals still matter, even if they now unfold inside apps instead of clumsy plastic trays.

References and further reading

- Compact Disc - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Compact_disc

- Discman - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Discman

- Napster - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napster

- Mixtape - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mixtape

Interviews cited in this article were conducted with:

- Dr. Lina Morales - Music historian (interviewed for this article)

- Ethan Kline - Collector and curator of portable players (interviewed for this article)