· culture · 6 min read

Portable CD Players: The Underestimated Artifacts of 90's Geek Culture

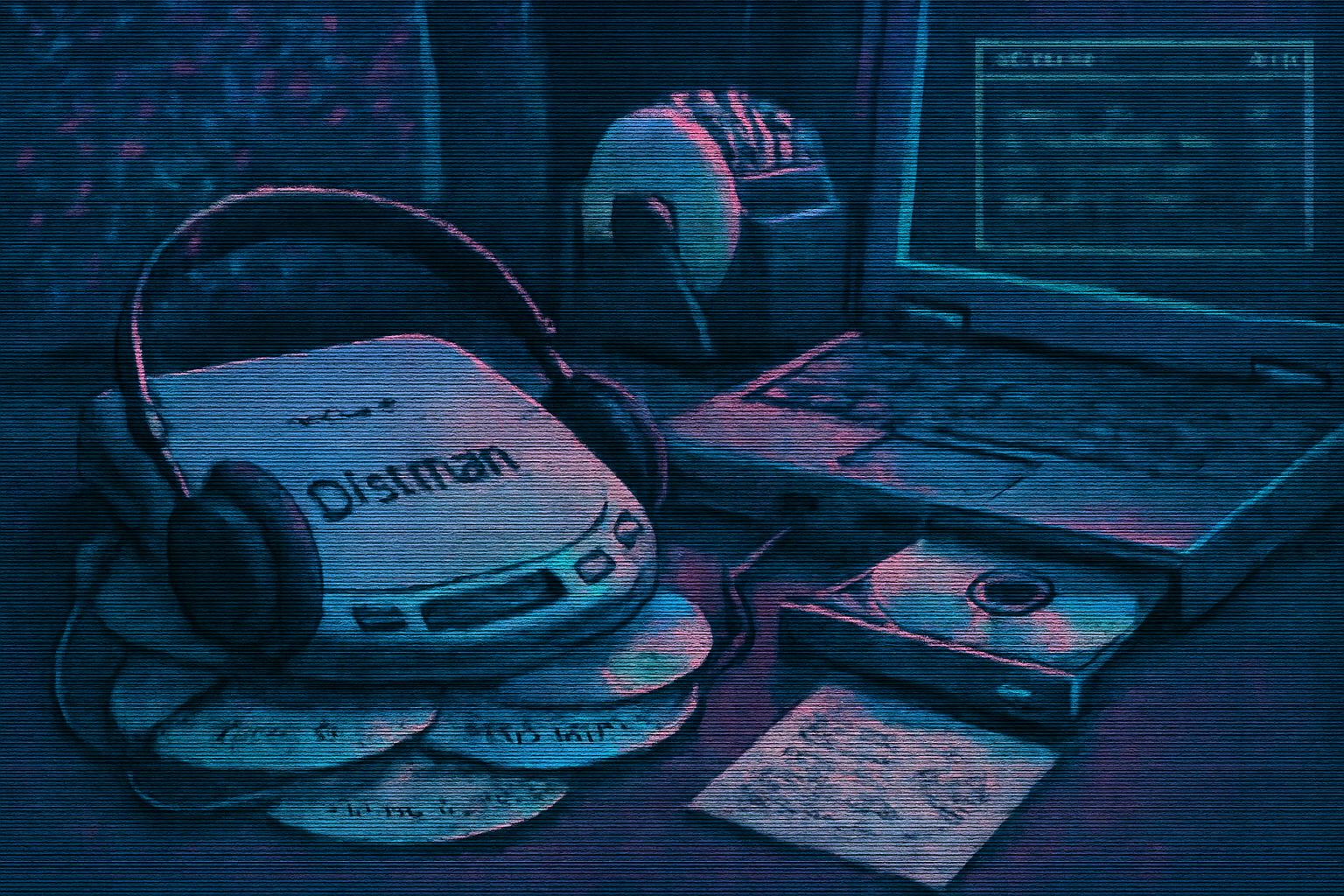

Portable CD players - the Discman and its clones - were more than shiny accessories. They rewired how geeks consumed sound, how game makers designed experiences, and how portable media evolved into today's playlist-driven world.

It begins with a memory so small it almost refuses to be true: a kid sprinting down a suburban sidewalk in 1996, Discman clipped to a belt, headphones like earmuffs against the rain of busyness that is adolescence. The player skipped on the curb. The kid swore. The music kept playing, in fits and starts. Nobody noticed the miracle - a tiny laser reading a spiral of microscopic pits - because the miracle had been domesticated. It was just sound, portable, personal, immediate.

That domestication is the story. The portable CD player is treated now like a quaint accessory - an anachronism in a museum of rectangles. But in the 1990s it was a cultural accelerant. It changed the texture of private time, the architecture of game soundtracks, and the industry expectations that would culminate in mp3 players and smartphones.

The obvious invention, the underrated consequence

Sony’s Discman - the first mass-market portable CD player - arrived in the mid-1980s and became ubiquitous by the 90s [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Discman]. Someone mature enough to scoff at its bulk today will forget that it made a promise that mattered: recorded music could escape the living room without surrendering fidelity. The Discman was a bet against the complacency of the home stereo. It brought the Red Book audio standard for CDs - the source of that warm, full sound - into pockets and backpacks [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red_Book_(audio_CD_standard)].

But this is where historians of technology get sentimental in the wrong place. The Discman’s true gift was not fidelity; it was expectation. It trained a generation to expect high-quality, track-random-access, portable sound. Those expectations would become design constraints for every device that followed.

Gaming soundtracks: from chip beeps to orchestras on a disc

The 90s gaming industry drank from the same fountain. When consoles and PCs embraced the CD-ROM, designers were given more than storage - they were handed a whole new palette for audio.

- The Sega CD add-on and Sony’s PlayStation exploited CD audio and CD-ROM data to deliver CD-quality music and full-motion video, changing game narratives and atmospheres [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sega_CD] [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/PlayStation].

- Landmark titles like Final Fantasy VII showed how much texture a soundtrack could add to storytelling when the medium stopped being punishingly small [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Final_Fantasy_VII].

Before CDs, game music was heroic in its constraints - composers coaxed emotion from a handful of channels and 8-bit beeps. CDs enlarged the stage. Suddenly developers could use live-recorded tracks, licensed songs, and orchestral pieces. Portable CD players meant that those soundtracks didn’t stay in front of the TV - players could and did become mixtapes for commutes, study sessions, and emotional regulation.

Demo discs, cover CDs, and communal curation

Computer magazines and console demo discs created a feedback loop between media and fandom. Buying a magazine sometimes felt like buying an event; the included CD-ROMs - demos, trailers, and utilities - were tasting menus for future purchases [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Covermount].

The physicality of discs also generated rituals of curation. The mixtape became the mix-CD. Swapping disks - burning them, labeling them, decorating them - was a social technology. It taught a generation the habit of building playlists, of curating listening experiences. That habit matters. The playlist is the dominant interaction model for audio services today.

The engineering ripple: shock protection, buffering, and user expectations

Portable players forced manufacturers and designers to solve real problems: how to keep a laser reading while your owner jogged or slammed car doors. Engineers developed clever buffering, anti-skip mechanics, and more robust pickups. Those lessons traveled: optical drives in consoles and laptops borrowed reliability improvements; UX designers learned to assume users would want interruption-resistant, immediate playback.

Those engineering investments had commercial consequences. The industry proved that consumers would pay for convenience plus fidelity. When mp3-compressed files and hard-disk players arrived, the market already believed in the value of portable, consistent audio.

From Discman to Napster to the iPod: a surprisingly direct lineage

It’s tempting to tell a neat story - Discman gives way to mp3 players; mp3 players get cannibalized by smartphones - but the truth is a braided lineage.

- CD-R and affordable burners democratized content creation and playlists in the mid-to-late 90s, turning consumers into producers of mix CDs [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CD-R].

- The Rio PMP300 (1998) and other early mp3 players proved there was a market for hard-drive-based music portability [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rio_PMP300].

- Napster’s appearance (1999) and the culture of file sharing forced the industry to reconcile convenience, access, and copyright [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napster].

But none of this would have landed as smoothly without the decades of accumulated user expectation that music could be personal, portable, and immediate. The Discman taught users the grammar of on-demand, private listening.

Cultural effects you can still hear and feel

Many of the Discman’s cultural imprints are subtle. They are not monuments but muscles you use without noticing:

- Headphone etiquette. The 90s normalized walking city streets with private soundtracks. Now, headphone culture defines commute behavior, public spaces, and personal bubbles.

- Playlists over albums. The mix-CD accelerated the idea that sequencing matters and that listeners are curators. Streaming services built their UI on that muscle memory.

- Expectations of fidelity in small devices. If you were used to CD quality on a Discman, you would notice early mp3 compression flaws - and you’d demand better.

A short inventory of artifacts and anecdotes

- The Discman skipping at a race - literal fragility becoming a badge of effort.

- Demo discs that sold a console generation before the game existed.

- Mixtapes reborn as mix-CDs and later as burned MP3 compilations shared on floppy-laden-to-CD-ROM-era BBSes.

Each artifact is small, but together they describe a cultural shift: the acoustics of privacy moved out of the living room and into pockets and backpacks.

Why this matters now

We live in a world designed for instant, high-quality, portable media. We treat that as inevitable. It isn’t. The portable CD player was one of the first widely available objects that normalized this way of being. It taught both consumers and creators to expect portability without compromise.

In design terms: the Discman taught a generation that the user experience must survive motion, that storage and playback should be reliable, and that music is more than background - it is a companion. Those design constraints echo in everything from smartphone OS design to audio codecs and streaming UX.

Final note - an elegy and a push

The Discman is easy to mock now: bulky, battery-hungry, archaic. But that mockery is a little impolite. It was, in its way, revolutionary. It was a bridge between the living-room rituals of recorded music and the always-on, personally curated soundscapes we live with today.

If you still have one in a drawer, take it out. Put on headphones. Listen for the tiny, precise mechanical hiss of a laser doing the work we now take for granted. It’s the sound of expectations being rewritten.

References

- Discman - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Discman

- Red Book (audio CD standard) - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red_Book_(audio_CD_standard)

- PlayStation - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/PlayStation

- Sega CD - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sega_CD

- Final Fantasy VII - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Final_Fantasy_VII

- Covermount (demo discs & magazine CDs) - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Covermount

- CD-R - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CD-R

- Rio PMP300 - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rio_PMP300

- Napster - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napster