· culture · 6 min read

From Beeper to Smartphone: The Evolution of Mobile Communication and What We Lost Along the Way

A nostalgic, critical look at how we moved from pagers to smartphones - what conveniences we gained and what social skills and quiet were quietly surrendered. Practical rituals to reclaim conversation included.

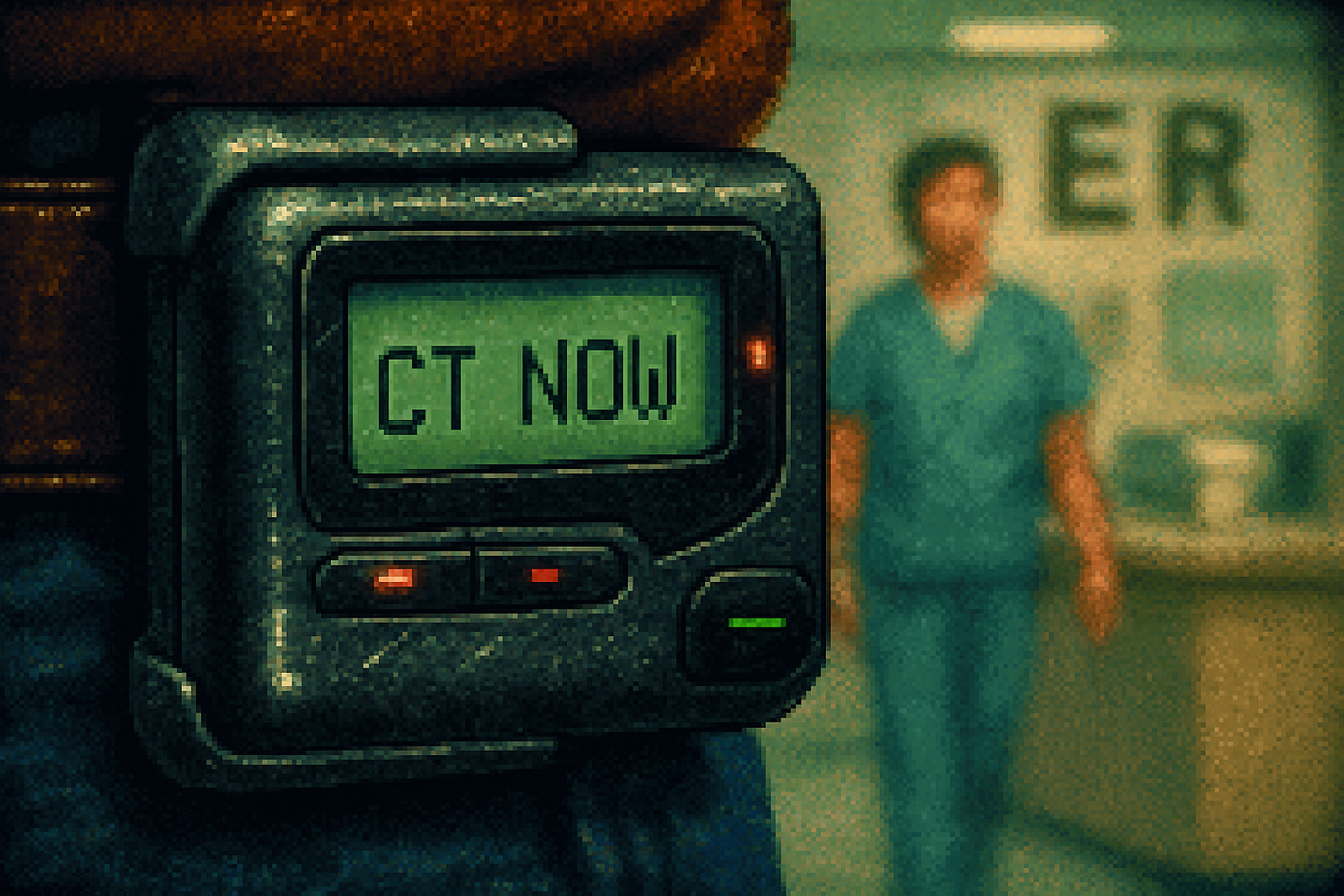

I still remember the sound: a single, tinny chirp from a pager tucked into a hospital coat pocket, followed by a tiny orange pixel telling you to call back. There was ritual in that beep. You paused. You finished the sentence you were saying. You walked to the hallway. You called. Conversation had a beginning and an end.

Fast-forward two decades. My phone vibrates in my hand-again-while I’m in the middle of a conversation. I glance down. She notices. The conversation falls into a peculiar, mutual embarrassment: an interruption that never announces itself, because the interruption is constant.

This is the story of a technological transformation that looks like progress on paper and feels ambivalent in the bones: from pagers and discrete, contained alerts to smartphones and the perpetual present. What we gained-instant access, maps, cameras, a thousand apps-was real and huge. What we lost-ritual, attention, the art of turning toward another human without a tether-was quieter. But it matters.

From beeps to broadband: a short history

Pagers (or beepers) were not glamorous, but they were functional. Used widely by emergency services and professionals in the 1970s–1990s, they broadcast a simple message: someone needs you now. The Wikipedia entry on pagers traces this arc from bulky start to the thin alphanumeric devices that dominated the ’80s and ’90s.

Then came the phone that changed the game. Apple’s 2007 introduction of the iPhone - the device that married a computer to a phone without ceremony - shifted expectations about what a mobile device could be (Apple newsroom, 2007). In little more than a decade smartphones spread to most pockets; by 2019, Pew Research reported that smartphone ownership had become mainstream in many countries.

Pagers were tools for urgent interruption. Smartphones are tools for everything-urgent and trivial alike. The difference is not incremental. It is cognitive.

What the pager taught us about boundaries

A pager was simple: it told you someone needed you, and then you chose when to respond. There was a boundary built into the device’s limitations. The message’s form forced deliberation.

The smartphone did away with that boundary. Notifications are never only about content; they are social signals. A ding can mean the boss, the mother-in-law, a late-night debate, or the algorithm nudging you back to an app. The device collapses scales of importance into the same sensation: vibration or chime.

Imagine conversation as a delicate vase. Pagers placed a lid on interruptions. Smartphones removed the lid and replaced it with glittering beads falling constantly into the vase.

The empirical problem: phones and the quality of conversation

This is not only a feeling. Social scientists have measured the effect. In a notable study, researchers found that the mere presence of a mobile phone reduces the perceived quality of face-to-face conversation and feelings of empathy and trust between participants (Przybylski & Weinstein, Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 2013). The phone need not ring; its mere presence on the table is enough to change how we relate.

Sherry Turkle, a longstanding critic of our digital intimacy, argues in books such as Reclaiming Conversation that the constant tether to others through devices has eroded our ability to listen deeply, to tolerate solitude, and to develop the reflective inner life necessary for empathetic conversation (Penguin Random House page for Reclaiming Conversation).

Put differently: we were good at being called. We are less good at being fully present.

What we traded away - in plain terms

Ritual and pause. Pagers enforced a rhythm. Smartphones encourage an everywhere-and-everywhen tempo. Rituals slow things down; they make certain encounters sacred. Without them, everything competes for attention.

Depth of attention. Rapid task-switching reduces comprehension and memory. The phone trains us to skim - notifications carve attention into flinders.

Transitional solitude. Those small pockets of waiting time-on a bus, in line, between meetings-used to be empty enough to wander mentally. Now they’re filled by scrolling. Our internal monologues have been outsourced.

Nonverbal nuance. Face-to-face communication relies heavily on micro-expressions, pauses, and rhythm. If your attention is half-here, you miss contours. Being physically present is necessary but not sufficient; attention matters.

The economy of absence. Absence has always been social glue. Not having immediate access persuades people to craft better messages, to value reciprocation, to respect time. Ubiquitous access dissolves that scarcity.

The deceptive comfort of constant connectivity

Smartphones sell a pleasant fiction: that continuous contact equals intimacy. But liveness is not the same as depth. “I saw your story” is not the same as “I listened.” The capacity to exchange a hundred quick messages replaces the capacity to sit through a single long, difficult one.

This is not the same as lamenting technology. I love maps. I love being able to check a doctor’s note. But we must be precise about trade-offs. Smartphones did not merely give us conveniences; they rewired our social architecture.

The exceptions and the nuance

Not all smartphone use is corrosive. Emergency access saves lives. Remote relationships across distance are kept alive precisely because of these devices. Pagers were perfect for urgency; smartphones are perfect for ubiquity. The problem is not the technology; it’s the default behavior-the passive acceptance that everything should be always-on.

How to get some of the lost back (practical rituals that work)

If you care about reclaiming conversational quality and attention, here are practical, testable rituals that don’t require Luddite heroism:

Physical separation - establish the phone-as-material-object rule. Leave phones in a basket in another room during dinner or put them face-down in a dedicated box during meetings.

The five-minute ritual - before starting a conversation, commit to five minutes of uninterrupted, phone-free listening. It signals focus and changes the tone.

Notification diet - disable nonessential notifications. Make badges a permissionless miracle, not an automatic demand.

Scheduled absences - calendar a regular “no-phone” hour-daily or weekly. Make solitude a practice, not an accident.

Device design for attention - use grayscale, fewer apps on the home screen, or a minimal launcher. Make the phone less alluring.

Social contracts - set expectations with friends and colleagues about response windows. If everyone assumes immediate reply, everyone is enslaved to immediacy.

Practice public attention - when with people, periodically announce that you are putting the phone away. It’s small theater, but theater builds trust.

A final note on moral clarity

This is not a puritanical plea against pleasure. Nor is it nostalgia for a past that was never perfect. It is a clear-eyed argument: technology is not neutral. When a device is designed to capture attention as its primary metric of success, we should expect social consequences.

We moved from pagers to smartphones because we wanted to be more connected. We got that, and we should not be surprised when the connection changes us. The question now is simple: do we let design companies govern the shape of our attention and our conversations, or do we reclaim a measure of intentionality?

Answering that question is not a call to burn your phone. It’s a request to choose, repeatedly, and publicly, the small rituals that make conversation possible.

References

- Pager history: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pager

- iPhone announcement (Apple, 2007): https://www.apple.com/newsroom/2007/01/09Apple-Revolutionizes-the-Cell-Phone-with-iPhone/

- Przybylski, A.K., & Weinstein, N. (2013). The mere presence of mobile communication technology influences face-to-face conversation quality: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0265407512453827

- Sherry Turkle, Reclaiming Conversation: https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/317819/reclaiming-conversation-by-sherry-turkle/