· retrogaming · 7 min read

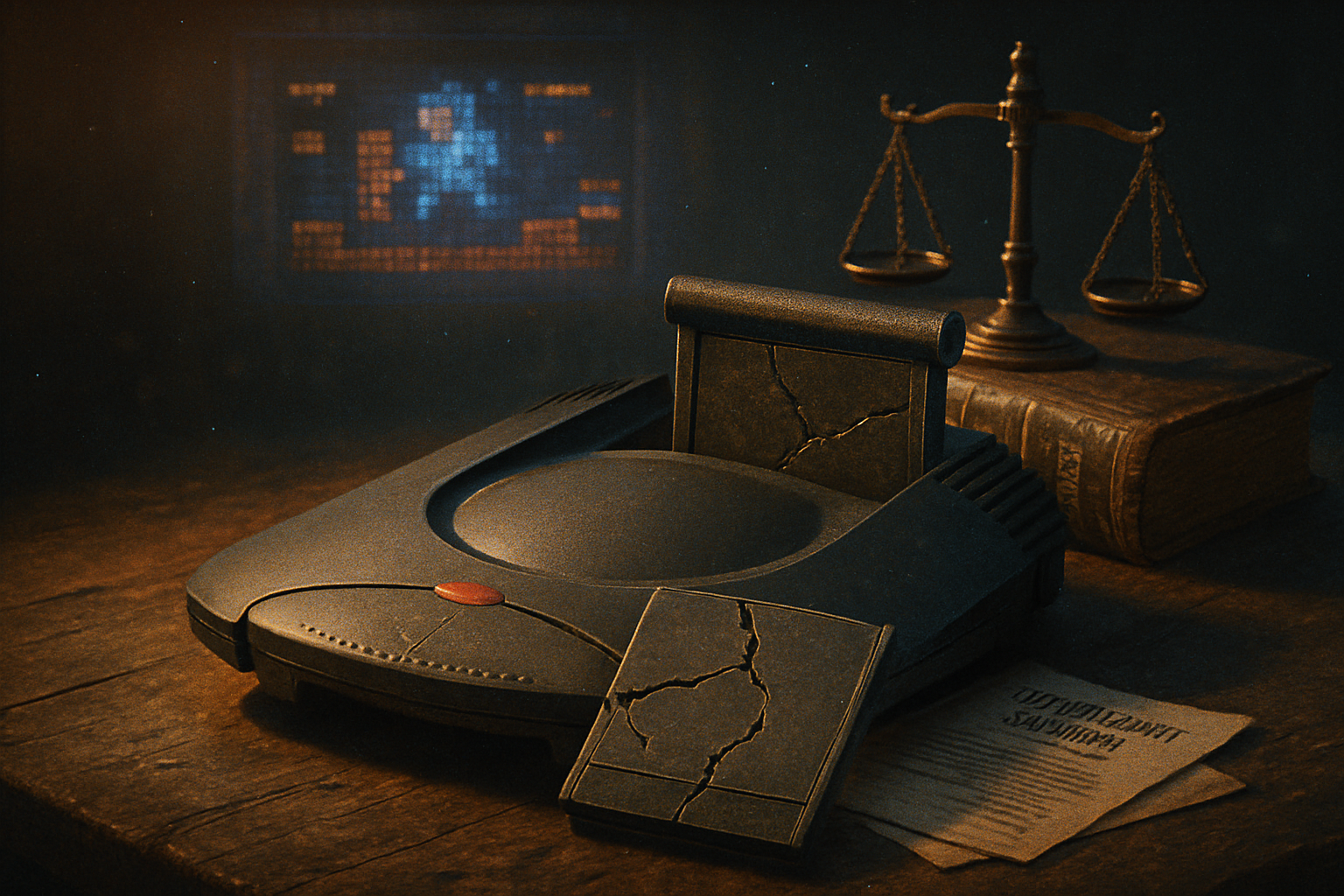

The Ethics of Emulation: Is it Illegal or Just Misunderstood?

PlayStation emulators live in a legal gray zone: the emulator code can be lawful, but BIOS and ROM distribution usually isn’t. This essay explains the law, history, developer rights, and where preservation fits in.

It began with a tiny piece of code and a courtroom. In 1999 a scrappy company called Connectix released Virtual Game Station, software that let Macs run PlayStation games. Sony responded with a lawsuit. The case that followed did more than decide one company’s fate - it exposed the curious moral geometry of emulation: is it theft, invention, or something between?

The quick, blunt answer

- Writing an emulator is usually legal. Emulation itself - re-implementing hardware behavior in software - is a technical feat and, on its face, protected.

- Distributing copyrighted BIOS code or game ROMs without permission is typically illegal.

- The DMCA adds a layer of danger - circumventing technological protections can be unlawful even if the end use feels defensible.

So: emulators? Mostly lawful. ROMs and BIOS dumps? Often not. The moral and legal fog sits squarely between those two facts.

A little history that matters

Two cases you should know.

Betamax (1984) - The U.S. Supreme Court held that time-shifting TV with a VCR was a fair use and that a device with substantial noninfringing uses can’t be condemned simply because it can be used to infringe. This is the famous “Betamax” doctrine and the seed of the argument that tools can be lawful even if sometimes abused. See the decision:

Connectix v. Sony (2000) - Connectix reverse-engineered the PlayStation BIOS to build Virtual Game Station. The Ninth Circuit effectively held that making intermediate copies during reverse engineering can be fair use and that copying necessary for interoperability isn’t automatically illegal. The case didn’t legalize ROM distribution, but it gave emulation a crucial breathing room. See:

Between these rulings lies the practical modern landscape: the law recognizes legitimate, noninfringing uses of enabling technology - but it also leaves room for rights-holders and anti-circumvention law to clamp down.

Where the law bites: BIOS, ROMs, and the DMCA

BIOS and proprietary firmware - Many console emulators rely on the original console BIOS (the firmware). The BIOS is copyrighted. Distributing it without permission is usually infringement. Re-implementing a BIOS clean-room style (writing your own code that replicates behavior without copying) is lawful but difficult.

Game ROMs - A ROM image is a copy of a game’s code. Unless you have explicit permission, distributing or downloading a ROM is typically infringement. Even if you own the physical disc or cartridge, legal protections for “backups” are murky and vary by jurisdiction.

The DMCA’s anti-circumvention rules - In the U.S., the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) makes it illegal to bypass technological protection measures, even where copying might otherwise be fair use. That means jailbreaking a console or breaking an encryption scheme to extract a BIOS or ROM can be a DMCA violation. See the statute and related materials:

There are exceptions and carved-out permissions. The Library of Congress periodically issues narrow exemptions for certain kinds of research, security, or preservation - but they are limited and require careful reading. See recent exemptions here: Library of Congress DMCA exemptions.

Preservation vs. piracy: two legitimate instincts

Two camps argue with moral certainty.

Preservationists - Museums, archivists, and scholars see emulation as the only practical way to save digital culture. Hardware dies, disks rot, consoles become obsolete. Re-releases are selective and commercial; emulation can rescue obscure or culturally significant works for study and posterity.

Rights-holders and publishers - Companies argue that unauthorized copies undercut markets, disincentivize investment, and violate creators’ rights. From their perspective, an emulator bundled with pirated ROMs is theft packaged as nostalgia.

Both are right. Preservation is urgent. Companies should be able to monetize their IP. The clash becomes moral noise when either side treats the other as villainous rather than selfishly aligned to different incentives.

Notable skirmishes (and lessons)

Bleem! - A commercial PlayStation emulator in the late 1990s, Bleem! ran PlayStation games on PC, with enhancements. Sony sued and, while Bleem! won some legal skirmishes, the legal costs and pressure effectively smothered the small company. Lesson: Even a defensible legal position can be economically untenable.

Internet Archive and other preservation efforts - The Archive and museums have attempted to host playable games via emulation. These projects show both the cultural value and legal risk; rights issues frequently require takedowns or negotiation. See the Internet Archive’s software library:

Practical moral and legal rules of thumb

If you want to tinker, collect, or preserve responsibly, consider these guidelines:

- Writing emulation code? Fine. Publish your clean-room reimplementations and document your methods.

- Using a BIOS? Either use a reimplementation or obtain the rights. Don’t distribute proprietary BIOS images.

- Downloading ROMs from random sites? Avoid it. It’s almost always infringing and unsafe.

- Ripping your legally purchased games for personal use? Jurisdiction matters. In the U.S. it’s legally risky because of the DMCA anti-circumvention rules. In other places, fair dealing or backups may be clearer.

- Want to preserve games? Work with museums, libraries, or established preservation groups. They can sometimes secure licenses and leverage exemptions.

- If you’re a developer or publisher worried about emulation - Embrace it strategically. Re-release classics, offer official emulation, or make assets available to preservationists. Heavy-handed litigation often backfires in PR and costs more than creative licensing.

The ethical calculus: something like a framework

Think of emulation as oxygen. You don’t notice it until it’s missing - until your hardware dies, or a beloved game vanishes. But oxygen also fuels fires: emulation can enable piracy.

So weigh three things:

- Cultural value - Is the work at risk of being lost? Obscure titles and indie releases have higher preservation priority.

- Harm - Is your action likely to directly reduce the creator’s revenue or harm an ongoing market? Playing a 25-year-old, unreleased demo likely harms less than distributing current AAA titles.

- Means - Are you respecting authorship - e.g., reimplementing rather than copying? Are you seeking permission where feasible?

If cultural value is high, direct harm is low, and your means are morally careful, you’re closer to preservation than piracy.

What this means for different people

Hobbyists - Build emulators. Avoid distributing BIOSes or ROMs. If you must use copyrighted content, rip your own and keep it offline - and still be aware of DMCA risk.

Preservationists and institutions - Lobby for broader legal exemptions, collaborate with rights-holders, and document everything. Fight for a legal framework that recognizes the public interest in preservation.

Developers and publishers - Consider that re-releasing classics is both good PR and a revenue stream. Litigation should be a last resort; licensing and cooperation win hearts and markets.

Policymakers - The law hasn’t kept pace with digital preservation. Tighten definitions around fair use for cultural heritage and adjust anti-circumvention rules to allow bona fide preservation and interoperability.

Final verdict: illegal? misunderstood? both?

Emulation itself is not the villain. It is a remarkable technical craft - an act of reconstruction and engineering. The legal threats are real, though: distributing copyrighted BIOS or ROMs without permission is generally illegal, and the DMCA can criminalize otherwise defensible acts.

In short: emulation is often misunderstood when painted as simple piracy. But it is not inherently lawful either. The real moral question is how we balance companies’ rights to monetize and control their creations against society’s need to preserve and study digital culture.

We can have both: sensible law, principled preservation, and reasonable licensing. We simply haven’t made the bargain yet. Until then, emulation remains an ethical gray that rewards careful actors and punishes the reckless.

(This article explains legal history and ethical reasoning, not legal advice. If you need guidance for a specific project, consult a qualified attorney.)

References

- Sony Corp. v. Universal City Studios (Betamax): https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/464/417/

- Sony Computer Entertainment v. Connectix: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sony_Computer_Entertainment_v._Connectix

- DMCA (U.S. Copyright Office): https://www.copyright.gov/legislation/dmca.pdf

- Library of Congress DMCA exemptions: https://www.copyright.gov/1201/

- Internet Archive - Software Library: https://archive.org/details/softwarelibrary

- Bleem! and emulator litigation: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bleem!