· retrotech · 6 min read

The Controversial Legacy of the Amiga 1200: Behind the Scenes of Its Commercial Failures and Hidden Successes

The Amiga 1200 arrived with a whisper of promise and a chorus of missteps: better graphics, lukewarm marketing, poor timing, and a parent company in freefall. This article unpacks the strategic and economic choices that turned one of gaming’s most beloved machines into a commercial puzzle - and the surprising ways it still shaped games and culture.

I remember a picture from a 1993 computer fair - a teenager hunched over a battered CRT, an Amiga 1200 tucked under one elbow, swapping floppy disks like contraband. He had that look: joy mixed with the resigned awareness that this treasure sat on shaky ground. Commodore’s latest machine could do things that made you forget the future for an hour. But the future forgot the Amiga.

The Amiga 1200 occupies a peculiar place in tech lore: adored by creatives and gamers, derided by investors and historians. It was spectacular in some ways, laughably compromised in others. This is a close reading of why the A1200’s commercial fate diverged so sharply from its cultural legacy - and what modern tech companies should learn from the mess.

The scene and the claim

Short version: the Amiga 1200 failed commercially not because the machine was bad, but because Commodore combined poor timing, muddled positioning, thin pockets, and catastrophic marketing. The result: a product that was technically interesting and culturally influential, yet structurally unsellable.

Context: Commodore’s wounded crown

In the late 1980s Amiga had momentum. The Amiga 500 was a dominant home computer in Europe and had carved a niche for multimedia and games. But the industry landscape changed fast: the PC was getting cheaper and more capable, Japanese consoles got savvier and more aggressive, and Commodore was fighting internecine managerial crises.

- Commodore’s corporate instability and financial decline were real and public; the company declared bankruptcy a few years later, in 1994, after a string of strategic errors and missed opportunities (Commodore International).

- New rivals were not just machines; they were ecosystems. Sega and Nintendo sold plug-and-play confidence; PCs offered an improving developer base and business model.

Commodore had the technology but not the capital or the strategic clarity to translate it into durable market advantage.

Hardware: interesting choices, unfinished arguments

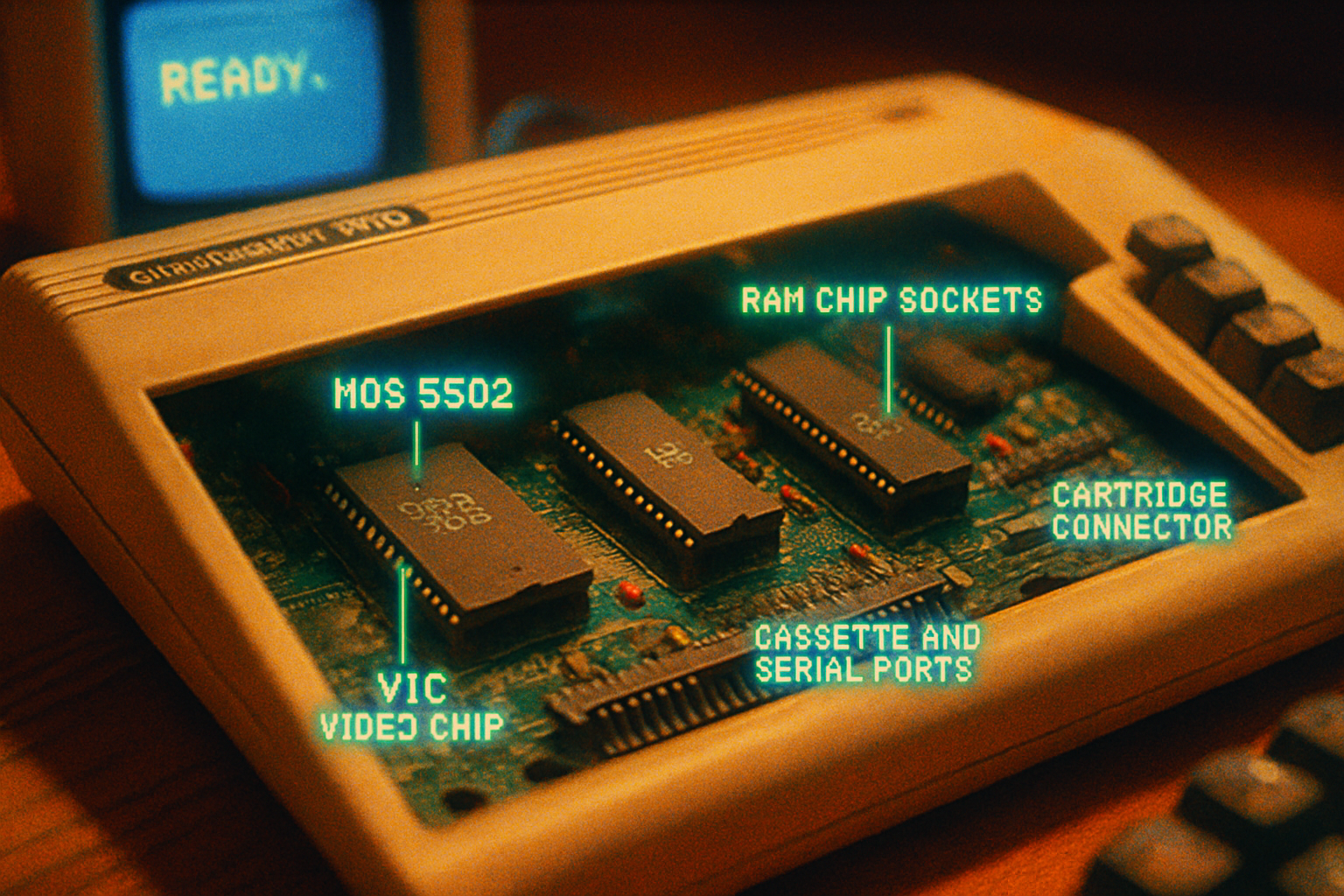

The Amiga 1200 introduced the AGA (Advanced Graphics Architecture) chipset - a genuine step forward for color depth and palette control compared with earlier Amigas. It added modern conveniences like PCMCIA and built-in IDE support on some variants that hinted at expandability and hybrid use-cases (Advanced Graphics Architecture).

But the inside felt half-committed:

- The CPU and baseline memory were modest for the price and expectations. Commodore trimmed costs in ways that hampered the machine’s ability to compete with emerging 32-bit workstations and accelerating PC hardware.

- The architecture kept many legacy constraints (helpful for backward compatibility, harmful for future-proofing).

Think of the A1200 like a sports car with a great chassis but a commuter engine. Beautiful to handle on a back road, frustrating on a highway.

Timing and positioning: too late, too many identities

Timing is a product feature. The A1200 arrived as the market’s tectonic plates were moving:

- Consoles offered cheap, standardized gaming experiences with strong publisher support.

- PC gaming’s tools, distribution, and user base were consolidating.

Commodore tried to position the A1200 as both an affordable home computer and a gaming powerhouse. The message was incoherent. The company flitted between selling it as the heir to the Amiga 500 and as a competitor for entry-level PCs.

Marketing failed where clarity mattered most. Commodore’s adverts emphasized specs to a demographic that didn’t know how to translate them into value. Meanwhile, console marketers sold feelings: friends, tournaments, and bright-brand icons - far more memorable than chipset improvements.

Software and developer economics: the ecosystem that wasn’t

Hardware without a thriving software ecosystem is like a movie theater with no films. The Amiga 1200 suffered from a thinning pipeline:

- Many developers had already shifted resources to PC or console markets where returns scaled better.

- Piracy on the Amiga platform was rampant and damaged software revenue, making the platform less attractive to publishers.

- Commodore’s underinvestment in developer tools, marketing support, and publisher relationships accelerated the flight of creative talent.

The result: fewer headline titles, fewer exclusives, and diminished discoverability for new users.

Corporate decisions that mattered

Three internal decisions accelerated the A1200’s decline:

- Product fragmentation - Commodore released many overlapping products (CDTV, CD32, Amiga families) that muddied the brand and cannibalized attention (

- Short-term cost cutting - components and choices prioritized lower BOM over longer-term competitiveness. That saved money today and lost market share tomorrow.

- Failure to pivot to services or licensing - Commodore could have cultivated platforms, licensing, or partnerships to spread risk; instead it remained vertically fragile.

This is corporate governance failure by numbers: strategic inconsistency, weak capital allocation, and no coherent roadmap.

Hidden successes: where the Amiga 1200 quietly won

It would be cruel to call the A1200 a total loss. Beneath the commercial wreckage the machine seeded several durable legacies:

- The demoscene - Amiga hardware was a playground for coders and artists who pushed the machine into spectacular visual and audio territory. Those demos are still studied and celebrated by generations of digital artists (

- A European games incubator - many UK and European studios cut their teeth on Amiga hardware; that experience fed the broader European game industry in the 1990s and 2000s.

- Hardware extendability and aftermarket - the Amiga community produced accelerators, expansions, and hacks that prolonged the machine’s life far beyond Commodore’s timeline.

- Cultural imprint - for a generation of players and developers, the Amiga’s aesthetic (chunky pixels, intricate soundtracks) shaped sensibilities that reappeared in indie games and retrospectives.

In short: commercially sidelined; culturally catalytic.

Anatomy of a product-market mismatch - a checklist

Here’s a compact checklist of what went wrong that product teams can take to heart:

- Misread the competitive set - console vs. PC vs. home computer wasn’t a three-way tie; each competitor had structural advantages.

- Mixed messaging - failing to pick a core value proposition - “creative workstation” or “affordable gaming machine” - diluted impact.

- Underinvest in the ecosystem - dev tools, publisher relations, anti-piracy measures, and marketing must be funded with the same seriousness as chip design.

- Timing negligence - shipping a moderately improved product into a fast-moving market is worse than shipping nothing. It’s a wasted market window.

- Corporate fragility - strategic blunders compound when cash is low and governance is poor.

Six lessons today’s tech companies should steal from the Amiga 1200

- Product is ecology, not isolated object. Think platforms - hardware, software, partners, and users must co-evolve.

- Messaging beats specs. If customers can’t articulate why they should care, you don’t have a product - you have a data sheet.

- Timing = relevance. Launch windows close fast. Be first, or be clearly better.

- Invest in creators. Developers and content makers are the lifeblood of any interactive platform.

- Avoid fragmentation. A dozen half-baked variants dilute developer attention and consumer trust.

- Guard financial runway. Strategic pivots require money. Without it, even brilliant machines die slow, undignified deaths.

A final, slightly cruel thought

The Amiga 1200 is a textbook case of a product that was loved into obscurity. It’s tempting to romanticize the device as a martyr of corporate malice. That’s modestly inaccurate. It was a victim of a more pedestrian enemy: bad strategy executed with indifferent competence.

And yet. Visit retro shows, join emulator forums, or watch old demos. The machine still hums in the cultural memory. That’s not failure in the absolute sense. It’s a lesson: short-term market success and long-term cultural influence are different currencies. Commodore squandered the first and, somehow, minted the other.

The Amiga 1200’s legacy is stubbornly ambivalent. It teaches product teams to love ecosystems, not just silicon - and to remember that the market punishes indecision more cruelly than it punishes audacity.

References

- Amiga 1200 - Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amiga_1200

- Commodore International - Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Commodore_International

- Advanced Graphics Architecture - Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Advanced_Graphics_Architecture

- Amiga CD32 - Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amiga_CD32

- Demoscene - Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demoscene