· retrotech · 6 min read

MP3.com: The Unsung Hero of Music Distribution

Before streaming made everything frictionless (and vaguely exploitative), MP3.com quietly rewired how artists reached listeners. This post traces its rise, legal fall, and the lessons modern musicians and platforms should still be borrowing.

A friend once told me about the first time they heard a band they’d never see on a festival lineup: “I downloaded a song at 2 a.m., printed the lyrics, and felt like I’d discovered a secret.” That feeling - private, illicit, ecstatic - is the short story of late‑90s music culture. And for a moment, MP3.com was the neighborhood where those secrets lived.

How MP3.com sneaked music out of the gate

MP3.com launched in 1997 with a blunt ambition: move music where people were already headed - online. The service was not merely a convenience; it was a structural proposition. Instead of relying on radio programmers, record stores, or label A&R to decide which songs might travel, MP3.com gave creators a direct stage and listeners a direct doorway. The company and its founder, Michael Robertson, became shorthand for an idea that sounded obvious in retrospect: if attention could be digitized, so could distribution [(MP3.com - Wikipedia).

Two of the platform’s offerings deserve particular attention.

- The Original Artist Program (OAP) - a place where unsigned and independent musicians could upload tracks, get featured on charts, and have a chance at organic discovery. It turned the internet into a level playing field - at least for attention.

- My.MP3.com - a controversial service that attempted to let users access music they owned from remote servers. The idea seemed reasonable to early adopters; the major labels saw it differently and launched lawsuits that changed MP3.com’s trajectory.

Why MP3.com mattered - and why “mattered” is not past tense

Think of music distribution before MP3.com like a town with three bridges guarded by label tolls. MP3.com began building footpaths across the river. They were small, rickety, and a little illegal - but they worked. For independent artists, the platform did four crucial things:

- Democratized reach. Upload a track and it could be heard across time zones without pressing a single CD.

- Created meritocratic visibility. Site charts and searchability rewarded songs that listeners actually clicked.

- Provided early metrics. Plays, downloads and placement on site charts gave artists data they’d otherwise only dreamt of.

- Reduced distribution friction. Instead of spending months getting retail shelf space, artists could iterate quickly based on real listener feedback.

Those features are the backbone of modern direct‑to‑fan strategies: own your music, own your data, own your relationship to listeners. MP3.com didn’t invent the idea of artists reaching listeners directly. It did, however, operationalize it at scale at the moment when the web stopped being theoretical and started being cultural.

The legal flailing and the crowd that never forgot

Of course the record labels noticed. The My.MP3.com service - which let users access copies of CDs they claimed to own via MP3.com’s servers - prompted lawsuits from major labels who argued that duplication onto the site’s servers required licensing. The company was pushed into settlements and business retreats; its trajectory was truncated by legal battles that hinged less on moral clarity than on who owned what and how fast the law could move [(MP3.com - Wikipedia).

Legal pressure changed MP3.com’s product roadmap and investor narrative. It’s one thing to tinker with market mechanics. It’s another to build a business model on an unresolved legal scaffolding. That fragility - a brilliant idea outpacing the legal and commercial ecosystems that would permit it to survive - is the tragicomic refrain of internet-era startups.

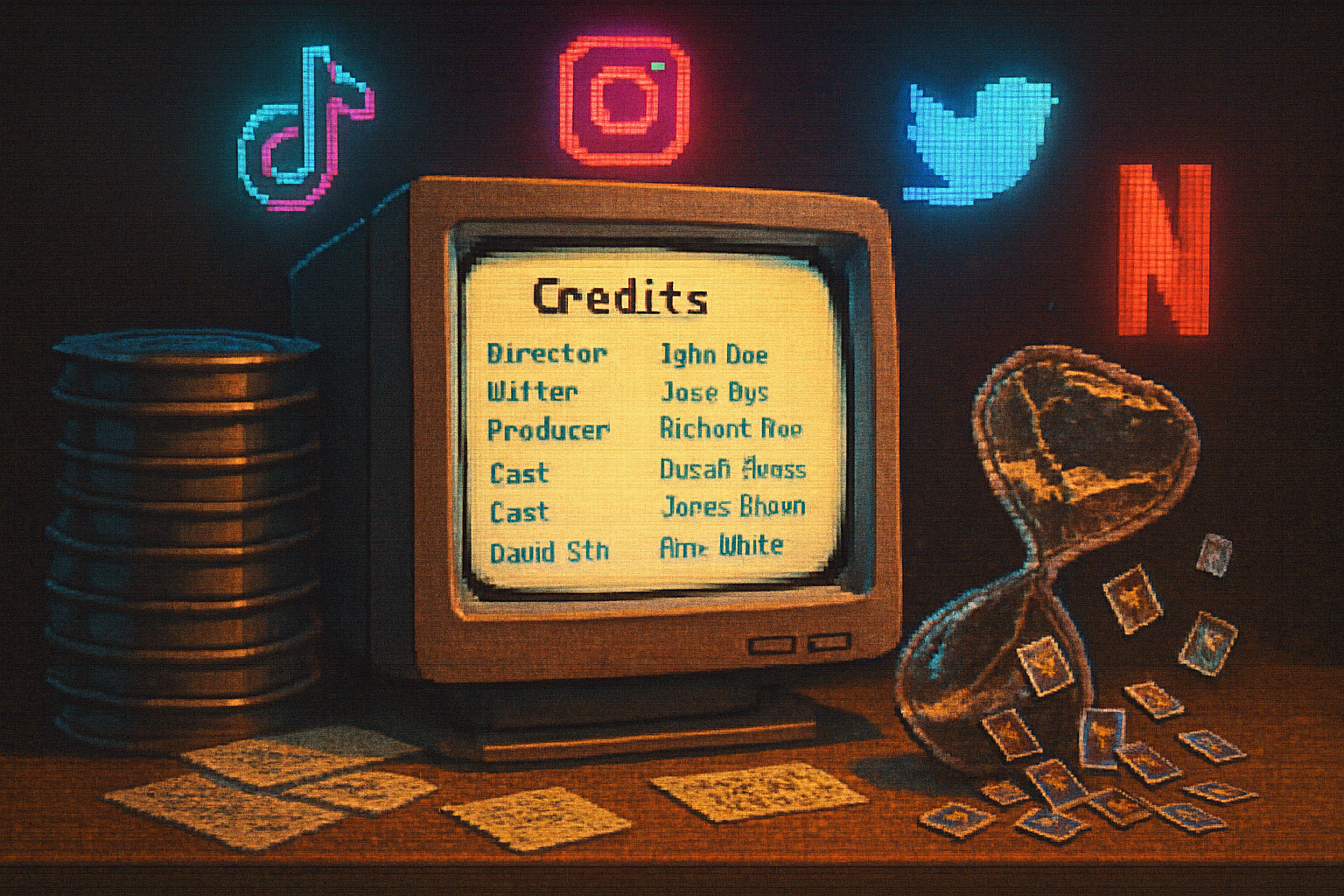

MP3.com’s real legacy: incentives, not servers

The platform’s most enduring gift to the music world wasn’t the storage racks or the logos; it was the incentive architecture it modeled. Three lessons emerged and live on in Bandcamp, SoundCloud, YouTube, and even Spotify’s editorial playlists:

- Attention infrastructures matter. MP3.com showed that simple discovery tools (search, charts, curated pages) could turn a stray upload into a sustainable audience.

- Data is power. Simple analytics gave artists leverage - the rudimentary ancestor of today’s artist dashboards.

- Gatekeeping can be reengineered. If distribution gatekeepers are vulnerable to displacement, platforms can be reimagined to favor creators.

Even platforms that later trended toward extractive monetization copied MP3.com’s mechanics. The difference today is that platforms learned to monetize attention at scale - sometimes to artists’ benefit, sometimes not.

How the lessons of MP3.com map onto today’s landscape

If MP3.com was a prototype for the direct‑artist era, then every subsequent platform is its heir - for better and worse. Here’s how those lessons help artists and industry players today:

- Own your audience, not just streams. MP3.com’s artists often converted listeners into repeat fans. Today, that translates into mailing lists, Discords, and Bandcamp followers. Streams are metrics; direct contact is currency.

- Use platform data to negotiate. Plays, geographic trends, playlist adds - these are bargaining chips. If MP3.com taught us one thing, it’s that raw listener behavior can be leveraged into opportunity.

- Expect legal and business friction. New distribution mechanics will always attract legal scrutiny; building resilience (diverse revenue, multiple platforms, owned assets) is prudent.

- Advocate for transparent economics. The early web offered the illusion of liberation; the lesson is - liberation without fair pay is a baited offer.

Platforms matter, but so does ownership. Bandcamp is often cited as the values‑oriented successor to MP3.com’s spirit: it pays artists well per sale and foregrounds the artist‑fan relationship [(Bandcamp).] SoundCloud, YouTube and Spotify have different tradeoffs - reach vs. revenue - but all owe a conceptual debt to MP3.com’s early experimentations [(SoundCloud, Spotify - Wikipedia).

Practical takeaways for artists and labels

For Artists

- Prioritize owned channels - email lists, merch stores, Bandcamp pages.

- Treat platform data as negotiating leverage - document trends and listener geography.

- Diversify - streams, direct sales, sync licensing, live appearances.

For Labels/Platforms

- Build transparent revenue-sharing primitives; artists will reward clarity.

- Invest in discovery tools that genuinely surface new talent, not just recycle incumbents.

- Remember that legal victories can generate bad PR; rights enforcement should be paired with creative transition strategies.

A final, unpleasant truth and a small consolation

MP3.com didn’t die because its idea failed. It faltered because an idea outran the legal and commercial scaffolding that might have carried it. The internet keeps producing these moments: bright protocols and better behaviors that collapse into contested courtroom exhibits.

But the consolation is that MP3.com’s spirit didn’t vanish with the domain. It lives in every Bandcamp sale, in every SoundCloud follower, in the dashboards that tell artists where their listeners live. The platform’s quiet revolution is now the default problem for the music industry: how to match vast reach with fair reward.

If you think the streaming era is inevitable and perfect, you haven’t listened closely to the people making the music. MP3.com’s lesson is not an elegy; it’s a blueprint. Build channels that let artists meet listeners on terms that are humane, transparent, and sustainable - and then make sure the artists get a bigger slice of the applause.

References

- MP3.com - Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MP3.com

- Bandcamp: https://bandcamp.com/

- SoundCloud: https://soundcloud.com/

- Spotify - Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spotify