· culture · 7 min read

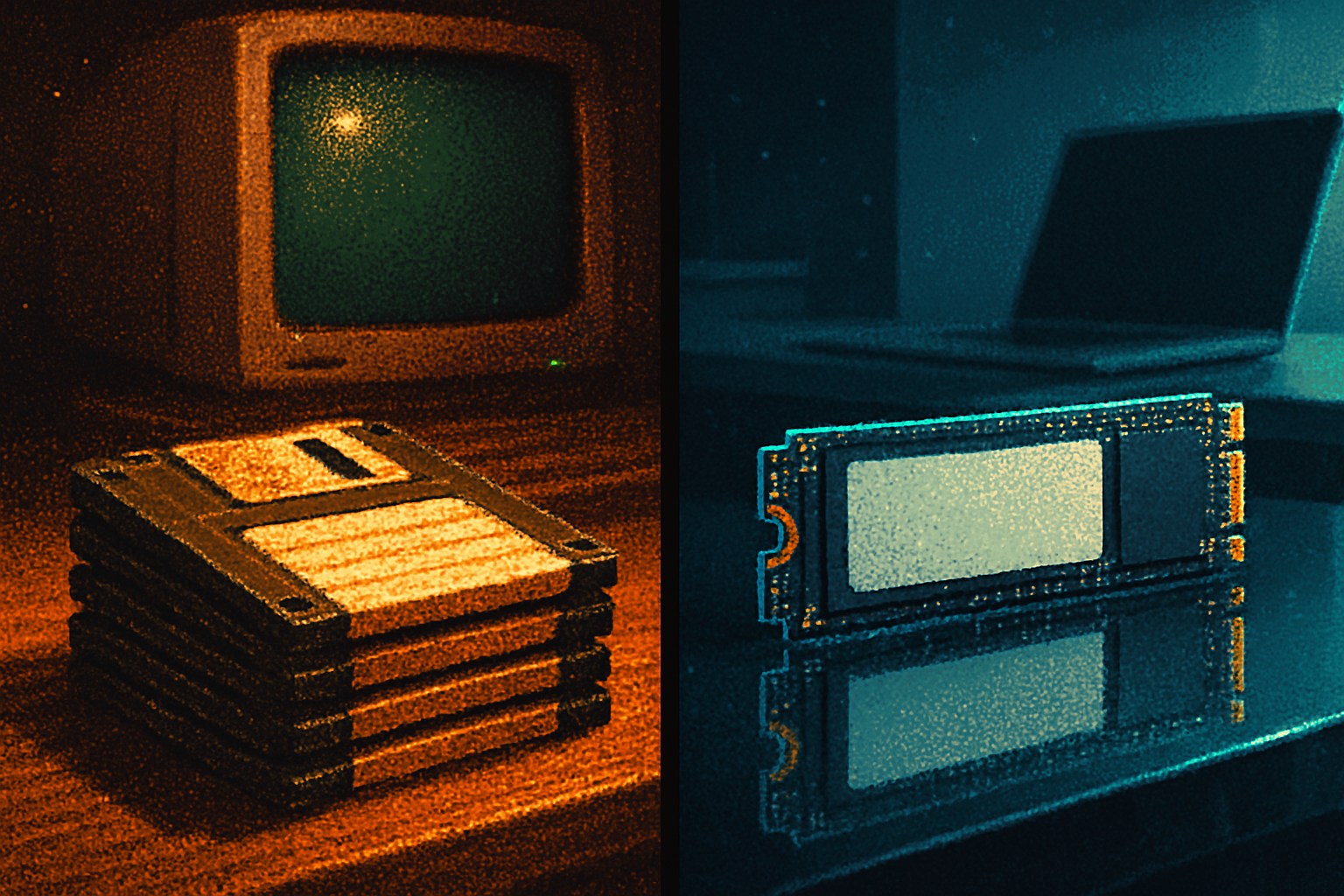

From Floppy to Cloud: The Evolution of Data Storage and What We Lost

A nostalgic yet skeptical look at how data moved from tactile, personal media like floppy disks to ephemeral cloud infrastructures - and what subtle, meaningful things we gave up in the trade for convenience and scale.

I still remember the click - a small, decisive snap as a 3.5-inch floppy slid into the drive, the satisfying physical confirmation that the file had a place to live. You labeled a disk with a Sharpie, stuck it in a box, and when you wanted that document again you went back to the box. There was friction, ritual, and responsibility. There was also an honest, human relationship with your data.

Fast forward thirty years and the ritual is gone. Your photos, invoices, drafts and secrets live in an abstract infrastructure called “the cloud” - a phrase as comforting as it is evasive. The cloud is convenient, glorious, and obedient. It also invites us to forget the work of remembering.

A short history: from magnetic flake to distributed servers

The floppy disk - in variants from the 8-inch originals of the early 1970s to the ubiquitous 3.5-inch format - made storage personal and portable in a way that previous technologies had not. IBM and other pioneers introduced removable magnetic storage that people could touch, label and misplace with equal vigor (Floppy disk - Wikipedia). Sony’s compact 3.5” disk and the PC boom sealed the floppy’s cultural role: it was how you saved things that mattered.

Storage then moved to denser local media - hard drives, CDs, USB sticks - and finally to a different architecture altogether: networked, elastic storage provided by companies like Amazon (S3 launched in 2006) and Dropbox (founded 2007) (Amazon S3, Dropbox - Wikipedia). Suddenly files were less about owning a physical object and more about accessing a service. If the floppy was a shoebox on your shelf, the cloud is a warehouse managed by someone else.

Convenience as the corroding agent

Convenience is seductive. It simplifies decision-making, collapses friction, and promises safety through redundancy. But convenience also changes behavior and expectation. Consider a few of the subtle shifts:

- Loss of ritual and attention. Saving to a floppy forced a pause - choose a disk, name it, physically store it. The cloud rewards immediacy and forgetfulness.

- Diffusion of responsibility. When your files live on a service, it feels like someone else is looking after them. That feeling often outpaces the reality of backup policies, retention periods, and business risk.

- Erosion of locality. Data used to occupy personal, discoverable spaces (desk drawers, desktop folders). Now it is distributed, indexed, and searchable - and equally dependent on the terms of a provider.

This isn’t merely nostalgia for plastic. The tactile experience created a different kind of relationship with our data: one where effort lent value, and loss produced real learning (you never forgot where the passport photos were if you lost them once).

What we actually lost

The cost of convenience is real, and it adds up in surprising ways.

- Ownership and control. “Your files” now often sit under legal terms you didn’t read. Account suspensions, corporate pivots, or new pricing tiers can make data effectively unavailable.

- Material cues and memory anchors. Physical labels, boxes and device inflections served as cognitive scaffolding. The smell of an old floppy or the creak of a hard drive mattered - they were memory prompts.

- Software and format durability. Floppies and early file formats required effort to open today, yes, but the actual practice of exporting, migrating and curating files was a visible part of digital life. The cloud hides those migrations until suddenly they’re painful or impossible. See the warnings about the “digital dark age” when formats and platforms vanish (Digital dark age - Wikipedia).

- Meaning through scarcity. When storage was limited and expensive, people had to decide what mattered. The result - curated collections, fewer duplicates, sharper organization. Today, infinite cheap storage encourages hoarding and deferred curation.

- A sense of friction that taught care. Friction is pedagogical. You learned to name files, to maintain backups, to archive. When everything ‘just syncs’, you may never learn or practice these useful survival skills.

What we gained - and why that matters

Let me be clear: this is not a vindication for floppy disks. Convenience also yielded huge societal gains:

- Scale and accessibility. The cloud lets a parent in Lagos share photos with family in São Paulo with zero postmaster work. Collaboration at scale is real and transformative.

- Reliability and redundancy (usually). Properly managed cloud systems offer replication, geographic redundancy, and uptime that a home user simply couldn’t achieve.

- New product and social forms. Software-as-a-service, streaming, and globally distributed apps depend on the cloud. Entire industries arise from that architectural model.

So convenience isn’t villainous. It enabled new human capabilities. The question is whether convenience should be the sole arbiter of how we treat data.

The cultural fallout: attention, responsibility and amnesia

There are cultural consequences beyond broken file formats and lost spreadsheets. The good life of ephemeral, frictionless tech trains a specific psychology:

- Expectation of perpetual availability. We act as though all data should always be accessible and searchable. We forget the economic and political choices that make that possible.

- Shrinking attention spans for maintenance. When your backups are ‘set it and forget it’, the very habit of maintenance atrophies. Infrastructure fails silently until it doesn’t.

- Vendor capture and lock-in. Moving terabytes between providers is nontrivial and expensive. The convenience that feels free can become a sticky trap.

The result is not just lost files; it’s a diminished capacity to steward a personal or institutional digital archive.

Concrete steps to reclaim agency (without abandoning convenience)

You can enjoy cloud convenience and still avoid becoming a data serf. Here’s a practical, realistic playbook:

- Have a 3-2-1 backup plan - three copies, on two different media, one off-site. That might be local SSD + cloud + offline drive.

- Export periodically. For services you care about, export archives and keep local copies. Most platforms provide data export tools (use them annually).

- Favor open formats. Prefer PNG, PDF/A, TXT, CSV over proprietary blobs. Open formats are your hedge against obsolescence.

- Practice curation. Once every 6–12 months, delete, tag, and reorganize. Scarcity used to teach this; conscious pruning replaces it.

- Read terms and set expectations. Know retention policies, geopolitical storage locations, and what happens to data upon account closure.

- Test restores. Backups are only useful if they restore. Exercise restores at least once a year.

- Consider local archives for irreplaceable materials. Photos of grandparents, legal docs, family archives - keep a local, offline master copy.

Metaphors that help: the shoebox vs. the warehouse

Think of data like possessions. A floppy is a shoebox in your closet - idiosyncratic, private, but fragile. The cloud is a climate-controlled warehouse rented by a company that may change its locks, shift your boxes, or refuse access when you miss a payment. Both have value. Both require choices.

The trick is to be a savvy tenant: enjoy the warehouse’s benefits, but keep the deed to what matters.

Conclusion: a modest proposal for habitual stewardship

We shouldn’t romanticize the past as a cure-all. Floppies were slow, small, and fragile. But they taught us to care. The cloud taught us to outsource effort and, in exchange, extended our reach. The right approach keeps the best of both: use cloud convenience where it multiplies human capability, but maintain rituals and infrastructure that preserve ownership, durability and memory.

That click when you inserted a floppy was tiny. But it was also a contract - a human act that said, “I will look after this.” In an age of infinite storage, the moral equivalent of that click is a conscious set of habits: export, curate, backup, and sometimes, unplug and hold things in your hands. Those are the practices that will keep our digital life intelligible, portable and humane - not simply available.

Further reading

- Overview of floppy disk history: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Floppy_disk

- Amazon S3 (origin of mainstream cloud storage services): https://aws.amazon.com/s3/

- Dropbox history and impact: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dropbox

- The digital dark age - why formats and platforms matter: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Digital_dark_age

- Bit rot and data degradation: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bit_rot