· retrotech · 7 min read

The Acorn Electron: A Controversial Choice in the British Computing Revolution

The Acorn Electron was supposed to be Britain’s affordable BBC Micro. Instead it became a study in clever engineering undone by timing, supply failures and brutal market forces. This article explains what Acorn got right, where it stumbled, and why enthusiasts argue it was more undervalued than failed.

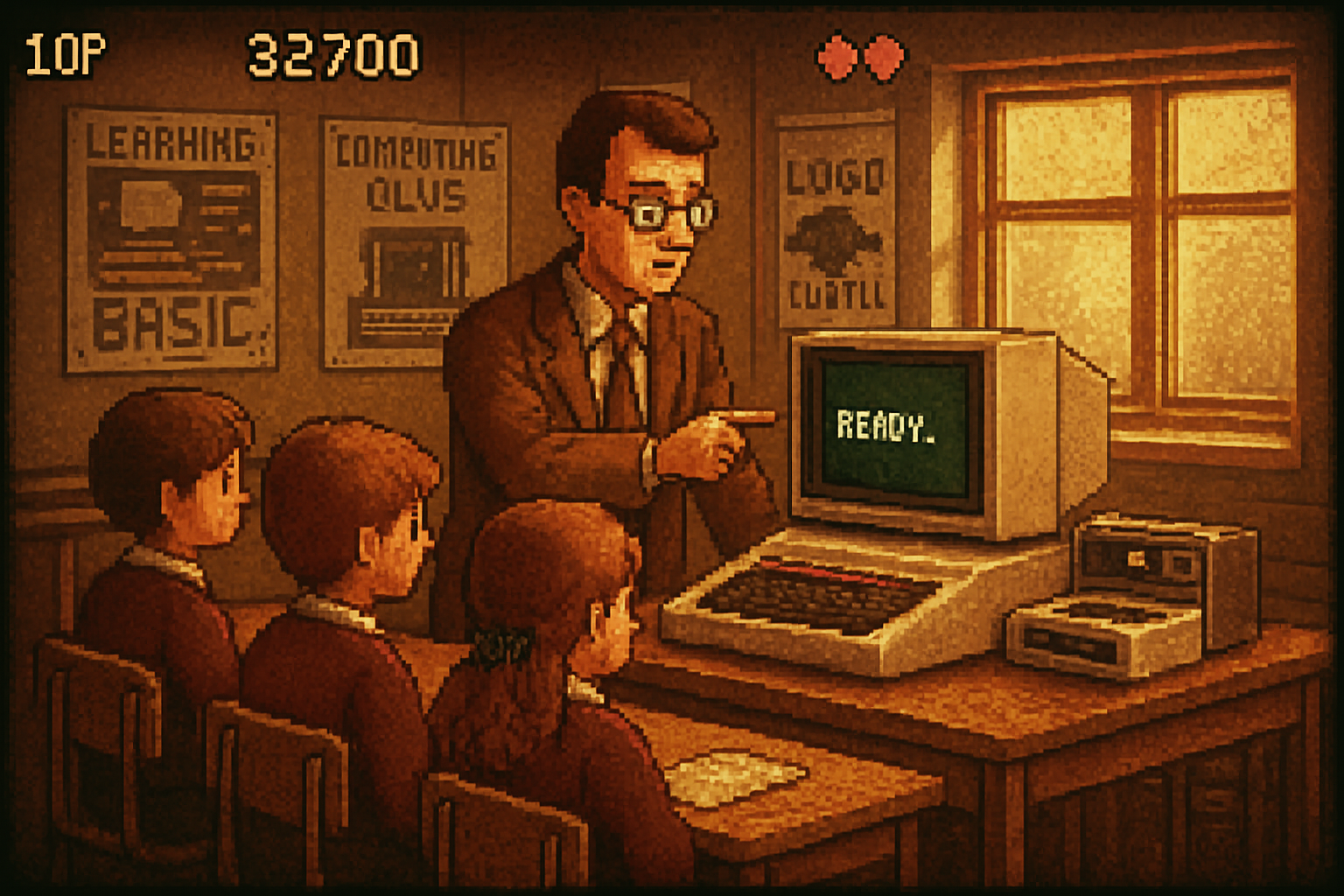

Opening with a scene: a living room in late 1983. A CRT TV glows. A cassette player clicks. A child - or more likely several of them - crowd round a compact beige box with an awkward, earnest keyboard. They type PRINT “HELLO” and the room cheers. That computer is the Acorn Electron: a cheaper cousin of the now-legendary BBC Micro. It was meant to make Britain’s BBC-backed computing revolution affordable for every household. Instead, it became a Rorschach test for the British microcomputer industry - admired by engineers, cursed by retailers, and roughly judged by the market.

Why the Electron existed: a short, sharp business imperative

After the BBC Micro’s success in the early 1980s - powered by the BBC’s Computer Literacy Project and a very visible place in schools - Acorn wanted the home market. The market leader in British living rooms was the Sinclair Spectrum; the Commodore 64 was pulling in dollars with sound and color. Acorn’s answer was simple in brief: give people a machine that was “like the BBC Micro” but cheaper. Make the educational pedigree accessible to kids who couldn’t afford the pricier Model B.

The goals were pragmatic:

- Keep BBC-compatible features where it mattered (BASIC, many graphics modes).

- Slash manufacturing cost and complexity.

- Ship a consumer-focused product with an aggressive retail price.

The result was the Electron: a machine that wore Acorn’s engineering pride but also the scars of cost-cutting.

Clever, compact engineering - the Electron’s unsung virtues

If you’re a hardware geek, the Electron is quietly impressive. Acorn replaced myriad discrete chips with a single custom ULA (Uncommitted Logic Array). The ULA’s job was to fold several functions into one silicon piece: video generation, memory contention logic, and other glue logic that previously required multiple support chips. The payoff was obvious: fewer components, simpler production, lower cost.

Other technical points worth praising:

- The Electron offered many of the BBC Micro’s display modes and a largely BBC-compatible BASIC, which meant that a good chunk of educational software and many games could be ported.

- It shipped with 32 KB of RAM - not extravagant but practical for the time and for most home use.

- It was compact and designed for the mass consumer market, not classroom lockers.

Those are not small achievements. Acorn’s engineers had managed to compress a classroom-oriented machine into something that could sit under a telly without bankrupting the buyer.

Sources: see contemporary histories and technical retrospectives for more detail on the ULA approach and design trade-offs (Wikipedia: Acorn Electron; Acorn-focused archives and community pages such as The Acorn Electron Website).

The compromises that turned clever into controversial

But every silicon trick has a trade-off. The ULA was cheaper - and smaller - but it also led to some nasty side effects:

- Memory contention and video timing quirks - to keep costs down the Electron shared RAM for CPU and video, and the ULA introduced contention cycles. Some software that assumed BBC Micro timings or used tight machine code ran poorly or not at all.

- Partial compatibility - while many BASIC programs and games could be ported, peripheral and low-level BBC software didn’t always behave. The Electron lacked some of the BBC Micro’s expansion friendliness out of the box, which mattered to hobbyists and schools.

- Limited I/O exposed to consumers without expansion - Acorn expected add-ons to fill the gaps - but add-ons cost money and slowed the out-of-the-box experience.

In other words: the Electron was very much a machine of trade-offs. It got the headline-cost down, but it didn’t fully inherit the BBC Micro’s ecosystem with zero friction.

The fatal timing and supply problems

Engineering compromises would have been survivable had the Electron launched on time and in quantity. It didn’t. Manufacturing bottlenecks - famously tied to the custom ULA production and Acorn’s contract/manufacturing arrangements - meant the Electron arrived late and in painfully small numbers.

By the time stock reached shops in volume, the Spectrum and Commodore 64 had entrenched consumer mindshare, retail shelf space, and a booming game market. Worse, Acorn’s pricing strategy and marketing were outmaneuvered: you could get a C64 with superior color and sound or a Spectrum with an enormous software library for similar money. The Electron’s educational credentials were not enough to dislodge those choices.

The result: disappointed retailers, cancelled orders, and a narrative of failure that stuck to the Electron even as later improvements and add-ons appeared.

Sources on market timing and shortage stories: contemporaneous press and later retrospectives summarize the production problems (Wikipedia: Acorn Electron production issues; community histories such as Acorn Electron).

The education paradox: schools loved the BBC Micro - was the Electron ever a fair candidate?

Here’s a subtle point people forget: the BBC Micro’s dominance in schools was not only about hardware. It was about a visible campaign (the BBC Computer Literacy Project), compatible software, teacher training and supply contracts. Schools were buying BBC Micros and Model Bs partly because Acorn supported them and because the hardware had expandability and longevity for classrooms.

The Electron, pitched at homes, was not a simple drop-in substitute for schools - even if it carried much of the BBC lineage. There were some promising moves: Acorn and third-parties produced educational titles and hardware expansions for the Electron, but procurement decisions in education are conservative and slow. For classroom managers, guarantees, longevity and peripheral compatibility mattered more than a lower price tag.

So the paradox: the Electron could have broadened the BBC ecosystem to homes and then indirectly benefited education, but the reverse expectation - that schools would flock to a cheaper Acorn box - was unrealistic.

Why some people argue the Electron was undervalued

There are three overlapping reasons enthusiasts still defend the Electron as underrated:

- Engineering elegance - the ULA-driven design was a spectacularly efficient way to hit a retail price while preserving a lot of the BBC experience.

- The software renaissance - once the hardware shortage eased, a steady trickle of ports, games and educational titles appeared; a dedicated community sustained the machine long after mainstream retailers gave up.

- Cultural and historical weight - the Electron is part of the UK’s computing DNA. It introduced many kids to BASIC and computing concepts who otherwise might have never touched a micro.

These are not arguments about market share. They are arguments about legacy. If you judge success by influence and affection rather than immediate retail success, the Electron did better than most commercial narratives admit.

Where Acorn tripped - a quick checklist

- Over-ambitious cost reduction - the ULA cut costs but introduced compatibility and timing penalties.

- Manufacturing and supply chain failure - late, patchy deliveries killed momentum.

- Misread market positioning - the Electron wasn’t as compelling for game-focused buyers as the Spectrum or C64.

- Expectation mismatch with education buyers - what schools valued wasn’t just low cost.

Counterfactuals - two honest “what ifs”

What if Acorn had:

- Secured reliable ULA production earlier? The Electron could have hit shelves in 1983 with enough volume to become a legitimate third pillar in UK computing.

- Spent more on marketing and bundle deals? Better bundling with disk or educational packs might have nudged parents toward purchase instead of Sinclair or Commodore.

History is full of near-misses. The Electron is one of the most instructive.

Legacy: a cult machine with an unfair reputation

Today the Electron has a vibrant retro scene: restorations, emulators, hardware extensions and a steady stream of new software created by enthusiasts. That ongoing attention isn’t only nostalgia; it’s proof that the machine had a solid technical foundation and an emotional resonance.

To dismiss the Electron as a simple commercial failure is to miss the deeper lesson: hardware is judged by markets as well as merit, and sometimes the rules of retail beat engineering elegance.

Final verdict - controversial, yes; worthless, no

The Acorn Electron was many things: a brilliant cost-engineered compromise, a victim of timing and supply, and a machine that never quite lived up to the promise Acorn had set for it. It was undervalued as an engineering achievement and as a cultural actor in Britain’s computing revolution - even if it didn’t win the battle of household market share.

If you want a short moral: hardware can be both clever and commercially unsuccessful. The Electron proves that the British computing revolution wasn’t a tidy story of winners and losers - it was a messy, human tale of timing, silicon, and sales forecasts gone wrong.

Further reading and sources

- Acorn Electron - Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acorn_Electron

- The Acorn Electron Website - community archive: http://www.acornelectron.co.uk/

- BBC Micro and the Computer Literacy Project - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/BBC_Micro