· retrotech · 7 min read

The Decline of Productivity Software: A Deep Dive into Microsoft Works

Microsoft Works was many families’ first taste of digital productivity: inexpensive, compact, and bundled with countless PCs. This post traces its rise in the 1990s, what made it uniquely useful for home users, why it ultimately faded away, and what its decline tells us about today's productivity landscape.

Introduction

For millions of home users in the 1990s and early 2000s, Microsoft Works was the unassuming productivity companion that came bundled with new PCs. It wasn’t as feature-rich as Microsoft Office, but Works did just enough - a word processor, a spreadsheet, a simple database, templates, and a friendly interface - all at a tiny footprint and either free or very low cost. Over time, however, Works disappeared from store shelves and OEM builds. This article looks at why Works was so popular, the features that set it apart, the forces that drove its decline, and what that trajectory means for modern productivity tools.

Note: For a concise history and timeline, see the Microsoft Works entry on Wikipedia and Microsoft’s 2009 post about Office Starter as Works’ successor: Microsoft Works (Wikipedia), Introducing Office Starter 2010 (Microsoft Office Blog).

What Was Microsoft Works - a quick history

Microsoft Works traces its roots back to the late 1980s as a compact, integrated productivity suite aimed at home and small‑business users. Rather than replicating the breadth of Microsoft Office, Works prioritized a small disk/memory footprint, streamlined features, and affordability - often bundled by OEMs with new consumer PCs.

Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, Works evolved in small steps: improving the word-processor interface, adding spreadsheet capabilities, and introducing database templates and simple mail‑merge and publishing tools. It used its own file formats (.wps for documents, .wks for spreadsheets, .wdb for databases) and emphasized ease-of-use over advanced functionality.

Why Works was popular

Several concrete factors explain Works’ widespread adoption:

- Low cost and bundling - Many OEMs bundled Works with new consumer PCs, so end users got useful productivity tools without buying Office.

- Small footprint - Works ran well on low-end hardware and early Windows systems where full Office would be slow or expensive to license.

- Simplicity - The interface and feature set were oriented to non‑technical users - people who needed to write letters, track household budgets, or manage an address book.

- Integrated templates and tasks - Works offered templates and task-driven workflows (letter writing, budgets, labels) that reduced the learning curve.

- All-in-one packaging - For home users who didn’t need advanced macros or pivot tables, Works provided everything necessary in a single, tiny package.

The result: for users who wanted to type a resume, balance a checkbook, or manage contacts, Works was often “good enough” - and significantly cheaper and lighter-weight than the full Office suite.

Unique features and design choices

Works wasn’t just a scaled-down Office; it made deliberate tradeoffs and design choices that suited its target audience:

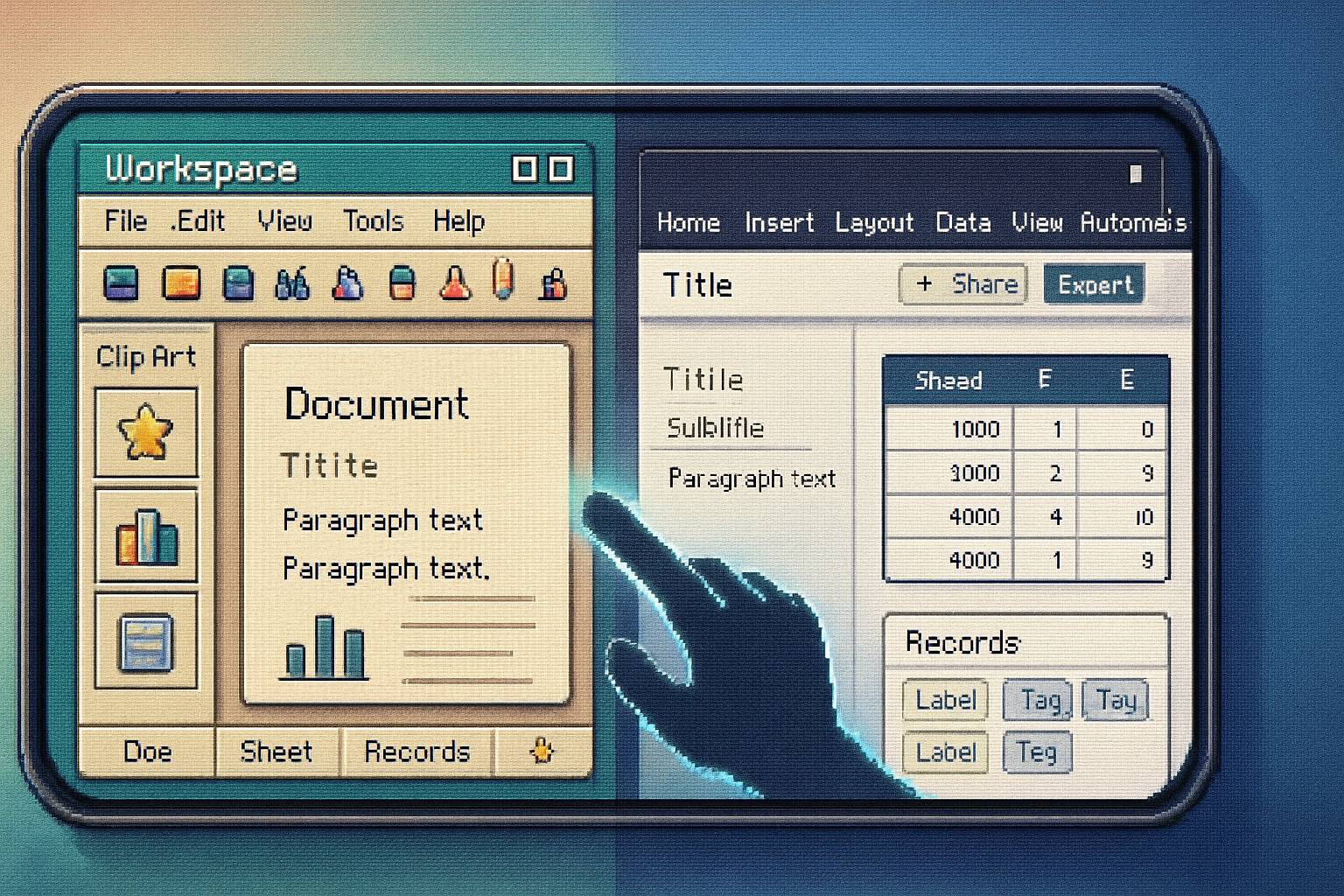

- Integrated mini‑apps - The word processor, spreadsheet and database could share templates and interoperate in simplified ways, enabling quick mail merges and labels without the complexity of Office.

- Task-oriented templates - A library of home-oriented templates (budgets, greeting cards, school projects) made common tasks straightforward.

- Fast startup and low system requirements - Works was engineered to perform acceptably on slow machines with small RAM and disk space.

- Simpler feature set = lower cognitive load - Features that existed in Works were often presented more accessibly - fewer options, clearer defaults.

Compared to contemporaries like WordPerfect, Lotus SmartSuite, or Microsoft Office, Works traded advanced features (macros, complex charts, enterprise integration) for immediacy and accessibility.

The decline - what changed

By the late 2000s Works began to lose relevance. Several converging forces drove its decline:

Hardware improvements and changing economics

As average PC hardware got faster and cheaper, the key advantage of a tiny-footprint suite evaporated. Installing a full Office suite became a practical choice for more users.

Microsoft product strategy

Microsoft’s own strategy shifted. In 2009 Microsoft positioned Office Starter (and later Office Online / Web Apps) as the lightweight alternative to full Office, and gradually phased out Works distribution in favor of these offerings and Office trial versions. That transition reflected product consolidation and the economics of promoting the paid Office ecosystem (Microsoft Office Blog).

File compatibility problems

Works used proprietary formats that sometimes made sharing with Office users awkward. As collaboration and document exchange grew more central to home and small-business workflows, compatibility friction mattered more.

Rise of free and cloud alternatives

A new wave of alternatives arrived: OpenOffice/LibreOffice offered more features for free; Google Docs brought web collaboration and real-time sharing; other lightweight suites (including mobile-first apps) addressed the casual‑user market. These alternatives often offered better interoperability and collaboration.

Changing distribution and monetization models

OEM bundling practices shifted (less preinstalled third‑party software), retailers moved away from supplying cheap bundled suites, and Microsoft had financial incentives to funnel users toward revenue-generating channels (paid Office, subscriptions).

New user expectations

As users adopted cloud storage, mobile devices, and collaborative workflows, the simple desktop-only emphasis of Works felt increasingly old-fashioned. People wanted cross-device sync, real-time collaboration, and more sophisticated formatting and compatibility.

Why Microsoft chose to discontinue Works

The decision to discontinue Works was less about a single technical failing and more about strategic priorities:

- Overlap with Microsoft’s other offerings (Office Home & Student, Office Starter, Office Web Apps).

- Low profitability and limited product differentiation in a market increasingly dominated by cloud services and free alternatives.

- The effort required to modernize Works (file compatibility, cross-platform sync, collaboration) would have been substantial with unclear returns.

In short: Works’ role as a lightweight entry point had been supplanted by new Microsoft products and by competitors better aligned with cloud and collaboration trends.

What Works’ decline teaches us about productivity software today

The arc of Microsoft Works illustrates several broader truths about productivity software:

Minimalism has value, but it must evolve. Lightweight apps remain useful - but users expect modern conveniences (sync, collaboration, compatibility).

Distribution matters. Bundling with OEMs helped Works scale. Today, distribution is dominated by app stores and web signups; visibility strategies have changed.

File formats and interoperability win. Proprietary formats create friction; openness (or compatibility layers) is strategically important for adoption and longevity.

Monetization shapes product design. Products that are loss-leaders or donations in a platform ecosystem have different fates than standalone commercial suites.

Users increasingly think in tasks, not suites. Modern productivity is often best served by specialized, interoperable apps (note-taking, collaborative docs, spreadsheets-as-a-service) rather than a monolithic suite of desktop tools.

The niche that survived - and those that didn’t

While Microsoft Works as a product faded, the idea of a lightweight, easy-to-use productivity tool did not. We see its spirit in:

- Cloud-first document editors (Google Docs, Office for the web)

- Mobile and web-native apps focused on single tasks (Notes, Sheets, Pages)

- Lightweight office suites targeting budget users (e.g., WPS Office, LibreOffice portable builds)

Conversely, the neat integration of Works’ templates and household-focused workflows is less visible; those use-cases have been absorbed into a constellation of specialized apps and cloud services.

Preservation and nostalgia

Works files still exist on old disks and hard drives, and many users want access to documents created in the 1990s and 2000s. The decline of Works underscores a perennial problem in computing: digital preservation. Converting legacy Works files to modern formats or keeping compatible viewers around matters for personal history and archival integrity. There are conversion tools and import filters in some modern suites, but the process is never seamless.

Conclusion

Microsoft Works was a product of its moment: a practical, approachable suite that helped millions of people perform everyday tasks on modest hardware. Its decline followed predictable technological and market shifts - improved hardware, the rise of cloud collaboration, new monetization strategies, and Microsoft’s own product consolidation.

The real lesson is not that lightweight productivity suites are dead, but that they must adapt. Today’s winners are the tools that keep simplicity without sacrificing interoperability, cross-device access, and collaborative workflows. Microsoft Works’ legacy survives in the expectation that productivity software should be accessible, task‑oriented, and easy to use - even if the form that expectation takes has moved from bundled desktop suites to cloud apps and mobile-first services.

References

- Microsoft Works - Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Microsoft_Works

- “Introducing Office Starter 2010” - Microsoft Office Blog: https://blogs.office.com/2009/11/05/introducing-office-starter-2010/

- “What Was Microsoft Works?” - How-To Geek: https://www.howtogeek.com/183392/what-was-microsoft-works/